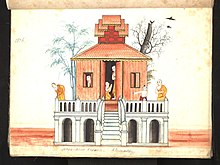

A kyaung (Burmese: ဘုန်းကြီးကျောင်း; MLCTS: bhun:kyi: kyaung:, [pʰóʊɰ̃dʑí tɕáʊɰ̃]) is a monastery (vihara), comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Buddhist monks. Burmese kyaungs are sometimes also occupied by novice monks (samanera), lay attendants (kappiya), nuns (thilashin), and white-robed acolytes (ဖိုးသူတော် phothudaw).[1]

The kyaung has traditionally been the center of village life in Burma, serving as both the educational institution for children and a community center, especially for merit-making activities such as construction of buildings, offering of food to monks and celebration of Buddhist festivals, and observance of uposatha. Monasteries are not established by members of the sangha, but by laypersons who donate land or money to support the establishment.

Kyaungs are typically built of wood, meaning that few historical monasteries built before the 1800s are extant.[2] Kyaungs exist in Myanmar (Burma), as well as in neighboring countries with Theravada Buddhist communities, including neighboring China (e.g., Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture). According to 2016 statistics published by the State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee, Myanmar is home to 62,649 kyaungs and 4,106 nunneries.[3]

Usage and etymology

The modern Burmese language term kyaung (ကျောင်း) descends from the Old Burmese word kloṅ (က္လောင်).[4] The strong connection between religion and schooling is reflected by fact that the kyaung is the same word now used to refer to secular schools.[5] Kyaung is also used to describe Christian churches, Hindu temples, and Chinese temples. Mosques are an exception, as they use the term word bali (ဗလီ), which is derived from the Tamil word for 'school.'

Kyaung has also been borrowed into Tai languages, including into Shan as kyong (spelt ၵျွင်း or ၵျေႃင်း)[6] and into Tai Nuea as zông2 (ᥓᥩᥒᥰ, rendered in Chinese as Chinese: 奘房).

Types

The Burmese-Pali commentaries of Cullavagga identify five types of Buddhist monasteries, each typified by distinct architectural features.[7] In practice, from an architectural standpoint, there are 3 main types of monasteries:[7]

- Monasteries with contiguous roofs,

- Monasteries with cross-shaped roofs, and

- Staging monasteries and staging halls

In modern-day Myanmar, kyaungs may be divided into a number of categories, including monastic colleges called sathintaik (Burmese: စာသင်တိုက်; MLCTS: casang.tuik) and remote forest monasteries called tawya kyaung (Burmese: တောရကျောင်း; MLCTS: tau:ra. kyaung:). Myanmar's primary monastic university towns are Bago, Pakokku, and Sagaing.[2]

History

In pre-colonial times, the kyaung served as the primary source of education, providing nearly universal education for boys, representing the "bastion of civilization and knowledge" and "integral to the social fabric of pre-colonial Burma."[1][8] The connections between kyaungs and education were reinforced by monastic examinations, which were first instituted in 1648 by King Thalun during the Taungoo Dynasty.[9] Classical learning was transmitted through monasteries, which served as venues for Burmese students to pursue higher education and further social advancement in the royal administration after disrobing.[10] Indeed, nearly all prominent historical figures such as Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung spent their formative years studying at monasteries.

Traditional monastic education first developed in the Pagan Kingdom, in tandem with the proliferation of Theravada Buddhism learning in the 1100s.[8] The syllabus at kyaungs included the Burmese language, Pali grammar and Buddhist texts with a focus on discipline, morality and code of conduct (such as Mangala Sutta, Sigalovada Sutta, Dhammapada, and Jataka tales), prayers and elementary arithmetic.[1] Influential monasteries held vast libraries of manuscripts and texts.[10] The ubiquity of monastic education was attributed with the high literacy rate for Burmese Buddhist men.[11] The 1901 Census of India found that 60.3% of Burmese Buddhist men over twenty were literate, as compared to 10% for British India as a whole.[11]

Kyaungs called pwe kyaungs (ပွဲကျောင်း) also taught secular subjects, such as astronomy, astrology, medicine, massage, divination, horsemanship, swordsmanship, archery, arts and crafts, boxing, wrestling, music and dancing.[12] During the Konbaung Dynasty, various kings, including Bodawpaya suppressed the proliferation of pwe kyaung, which were seen as potential venues for rebellions.[12]

Sumptuary law dictated the construction and ornamentation of Burmese kyaungs, which were among the few building structures in pre-colonial Burma to possess elaborate multi-tiered roofs called pyatthat.[13] Mason balustrades characterized royal monasteries.

Following the abolishment of the Burmese monarchy at the end of the Third Anglo-Burmese War, monastic schools were largely superseded by secular, government-run schools.[8]

Common kyaung features

The typical kyaung consists of a number of buildings called kyaung zaung (ကျောင်းဆောင်):[14]

- Thein (သိမ်, from Pali sīmā) - ordination hall as prescribed by the Vinaya

- Dhammayon (ဓမ္မာရုံ) - assembly hall used for sermons and communal purposes

- Zedi (စေတီ, from Pali cetiya) - stupa, often covered with gold leaf and containing a reliquary

- Gandhakuti (ဂန္ဓကုဋိ, from Pali gandhakuṭi) - pavilion that houses the monastery's principal image of the Buddha

- Shrines to the arhats Sīvali and Shin Upagutta

- Tagundaing[15] - ornamented flagstaff celebrating the submission of local nats (animistic spirits) to the Dhamma

- Zayat - open-air pavilions used as rest houses

- Living quarters for the monks and the sayadaw

- Kyetthayei khan (ကျက်သရေခန်း) - storage room

- Cooking quarters

Traditional monasteries of the Konbaung era consisted of the following halls:

- Pyatthat hsaung (ပြာသာဒ်ဆောင်) - main chapel hall that housed images of the Buddha[16]

- Hsaungmagyi (ဆောင်မကြီး) or hsaungma (ဆောင်မ) - main assembly hall for lectures, ceremonies and housing junior monks

- Sanu hsaung (စနုဆောင်) - residential hall of the monastery abbot

- Bawga hsaung (ဘောဂဆောင်) - storage room for monks' provisions

In pre-colonial times, royal monasteries were organized as complexes known as kyaung taik (ကျောင်းတိုက်), composed of several residential buildings, including the main building, the kyaunggyi (ကျောင်းကြီး) or kyaungma (ကျောင်းမ), which was occupied by the residing sayadaw, and smaller structures called kyaungyan (ကျောင်းရံ), which housed the sayadaw's disciples.[17] The complexes were walled compounds, and also housed a library, ordination halls, meeting halls, water reservoirs and wells, and utility buildings.[17] Thayettaw is a major kyaungtaik in downtown Yangon, comprising over 60 individual monasteries.

Examples

- Atumashi Monastery

- Bagaya Monastery

- Htilin Monastery

- Mahagandhayon Monastery

- Myadaung Monastery

- Salin Monastery

- Shweinbin Monastery

- Shwenandaw Monastery

- Shwezedi Monastery

- Taiktaw Monastery

- Yaw Mingyi Monastery

- Kongmu Kham, Arunachal Pradesh, India

- Foguang Temple, Yunnan, China

- Dhammikarama Burmese Temple, Penang, Malaysia

- Burmese Buddhist Temple, Singapore

See also

- Gautama Buddha

- Dhamma

- Sangha

- Three Refuges

- Five Precepts

- Eight Precepts

- Four Noble Truths

- Noble Eightfold Path

- Pāli Canon

- Mangala Sutta

- Samatha & Vipassanā

- Cetiya

- Sri Maha Bodhi

- Vassa

- Kathina

- Uposatha

- Shinbyu

- Gadaw

- Shwedagon Pagoda

- Thadingyut Festival

- Pagoda festival

- Pagodas in Myanmar

- Agga Maha Pandita

- State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee

- List of Sāsana Azani recipients

- International Theravada Buddhist Missionary University

- State Pariyatti Sasana University, Yangon

- State Pariyatti Sasana University, Mandalay

- Buddha Sāsana Nuggaha

- Young Men's Buddhist Association (Burma)

- Vihara

- Wat

References

- ^ a b c Houtman, Gustaaf (1990). Traditions of Buddhist Practice in Burma. ILCAA.

- ^ a b Johnston, William M. (2013). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-78715-7.

- ^ "The Account of Wazo Monks and Nuns in 1377 (2016 year)". The State Samgha Maha Nayaka Committee. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ^ Watkins, Justin (2005). Studies in Burmese Linguistics. Pacific Linguistics, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, the Australian National University. p. 227. ISBN 9780858835597.

- ^ Chai, Ada. "The Effects of the Colonial Period on Education in Burma". Educ 300: Education Reform, Past and Present. Trinity College. Retrieved 2016-11-26.

- ^ Sao Tern Moeng (1995). Shan-English Dictionary. 1995. ISBN 0-931745-92-6.

- ^ a b Robinne, François (2003). "The monastic unity. A contemporary Burmese Artefact?". Aséanie, Sciences humaines en Asie du Sud-Est. 12: 75–92.

- ^ a b c James, Helen (2005). Governance and Civil Society in Myanmar: Education, Health, and Environment. Psychology Press. pp. 78–83. ISBN 9780415355582.

- ^ "သာသနာရေးဦးစီးဌာနက ကျင်းပသည့် စာမေးပွဲများ". Department of Religious Affairs (in Burmese). Ministry of Religious Affairs. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- ^ a b Huxley, Andrew (2007). "Review of Powerful Learning: Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752–1885". South East Asia Research. 15 (3): 429–433. JSTOR 23750265.

- ^ a b Reid, Anthony (1990). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450-1680: The Lands Below the Winds. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300047509.

- ^ a b Mendelson, E. Michael (1975). Sangha and State in Burma: A Study of Monastic Sectarianism and Leadership. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801408755.

sangha and state in burma.

- ^ Fraser-Lu, Sylvia (1994). Burmese Crafts: Past and Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195886085.

- ^ World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. p. 630. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3.

- ^ Nisbet, John (1901). Burma Under British Rule--and Before. A. Constable & Company, Limited.

- ^ India, Archaeological Survey of; Marshall, Sir John Hubert (1904). Annual Report. Superintendent of Government Printing.

- ^ a b Lammerts, D. Christian (2015). Buddhist Dynamics in Premodern and Early Modern Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814519069.