Florence

Firenze (Italian) | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Firenze | |

|

| |

| Coordinates: 43°46′17″N 11°15′15″E / 43.77139°N 11.25417°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Tuscany |

| Metropolitan city | Florence (FI) |

| Frazioni | Baronta, Callai, Galluzzo, Cascine del Riccio, Croce di Via, La Lastra, Mantignano, Ugnano, Parigi, Piazza Calda, Pontignale, San Michele a Monteripaldi, Settignano |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sara Funaro (PD) |

| Area | |

• Total | 102.32 km2 (39.51 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2022)[2] | |

• Total | 367,150 |

| • Density | 3,600/km2 (9,300/sq mi) |

| Demonyms | English: Florentine Italian: fiorentino (m.), fiorentina (f.) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 50121–50145 |

| Dialing code | 055 |

| ISTAT code | 048017 |

| Patron saint | John the Baptist[3] |

| Saint day | 24 June |

| Website | Official website |

Florence (/ˈflɒrəns/ FLORR-ənss; Italian: Firenze [fiˈrɛntse] ⓘ)[a] is the capital city of the Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 364,073 inhabitants in 2024, and 990,527 in its metropolitan area.[4]

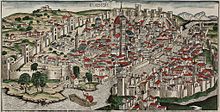

Florence was a centre of medieval European trade and finance and one of the wealthiest cities of that era.[5] It is considered by many academics[6] to have been the birthplace of the Renaissance, becoming a major artistic, cultural, commercial, political, economic and financial center.[7] During this time, Florence rose to a position of enormous influence in Italy, Europe, and beyond.[8] Its turbulent political history includes periods of rule by the powerful Medici family and numerous religious and republican revolutions.[9] From 1865 to 1871 the city served as the capital of the Kingdom of Italy. The Florentine dialect forms the base of standard Italian and it became the language of culture throughout Italy[10] due to the prestige of the masterpieces by Dante Alighieri, Petrarch, Giovanni Boccaccio, Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini.

The city attracts millions of tourists each year, and UNESCO declared the Historic Centre of Florence a World Heritage Site in 1982. The city is noted for its culture, Renaissance art and architecture and monuments.[11] The city also contains numerous museums and art galleries, such as the Uffizi Gallery and the Palazzo Pitti, and still exerts an influence in the fields of art, culture and politics.[12] Due to Florence's artistic and architectural heritage, Forbes ranked it as one of the most beautiful cities in the world in 2010.[13]

Florence plays an important role in Italian fashion,[12] and is ranked in the top 15 fashion capitals of the world by Global Language Monitor;[14] furthermore, it is a major national economic centre,[12] as well as a tourist and industrial hub.

Etymology

Firenze comes from Florentiae, locative form of Florentia, in turn a name conveying good luck, from Latin: florēre, lit. 'to blossom'.[15]

History

Historical affiliations

Roman Republic, 59–27 BC

Roman Empire, 27 BC–AD 285

Western Roman Empire, 285–476

Kingdom of Odoacer, 476–493

Ostrogothic Kingdom, 493–553

Eastern Roman Empire, 553–568

Lombard Kingdom, 570–773

Carolingian Empire, 774–797

Regnum Italiae, 797–1001

March of Tuscany, 1002–1115

Republic of Florence, 1115–1532

Duchy of Florence, 1532–1569

Grand Duchy of Tuscany, 1569–1801

Kingdom of Etruria, 1801–1807

First French Empire, 1807–1815

Grand Duchy of Tuscany, 1815–1859

United Provinces of Central Italy, 1859–1860

Kingdom of Italy, 1861–1943

Italian Social Republic, 1943–1945

Italy, 1946–present

Florence originated as a Roman city, and later, after a long period as a flourishing trading and banking medieval commune, it was the birthplace of the Italian Renaissance. It was politically, economically, and culturally one of the most important cities in Europe and the world from the 14th to 16th centuries.[11]

The language spoken in the city during the 14th century came to be accepted as the model for what would become the Italian language. Thanks especially to the works of the Tuscans Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio,[16] the Florentine dialect, above all the local dialects, was adopted as the basis for a national literary language.[17][18]

Starting from the late Middle Ages, Florentine money—in the form of the gold florin—financed the development of industry all over Europe, from Britain to Bruges, to Lyon and Hungary. Florentine bankers financed the English kings during the Hundred Years' War. They similarly financed the papacy, including the construction of their provisional capital of Avignon and, after their return to Rome, the reconstruction and Renaissance embellishment of Rome.

Florence was home to the Medici, one of European history's most important noble families. Lorenzo de' Medici was considered a political and cultural mastermind of Italy in the late 15th century. Two members of the family were popes in the early 16th century: Leo X and Clement VII. Catherine de' Medici married King Henry II of France and, after his death in 1559, reigned as regent in France. Marie de' Medici married Henry IV of France and gave birth to the future King Louis XIII. The Medici reigned as Grand Dukes of Tuscany, starting with Cosimo I de' Medici in 1569 and ending with the death of Gian Gastone de' Medici in 1737.

The Kingdom of Italy, which was established in 1861, moved its capital from Turin to Florence in 1865, although the capital was moved to Rome in 1871.

Roman origins

Florence was established by the Romans in 59 BC as a colony for veteran soldiers and was built in the style of an army camp.[19] Situated along the Via Cassia, the main route between Rome and the north, and within the fertile valley of the Arno, the settlement quickly became an important commercial centre and in AD 285 became the capital of the Tuscia region.

Early Middle Ages

In centuries to come, the city experienced turbulent alternate periods of Ostrogoth and Byzantine rule, during which the city was fought over, helping to cause the population to fall to as low as 1,000 people.[20] Peace returned under Lombard rule in the 6th century and Florence was in turn conquered by Charlemagne in 774 becoming part of the March of Tuscany centred on Lucca. The population began to grow again and commerce prospered.

Second millennium

Margrave Hugo chose Florence as his residency instead of Lucca around 1000 AD. The Golden Age of Florentine art began around this time. In 1100, Florence was a "commune", meaning a city-state. The city's primary resource was the Arno river, providing power and access for the industry (mainly textile industry), and access to the Mediterranean sea for international trade, helping the growth of an industrious merchant community. The Florentine merchant banking skills became recognised in Europe after they brought decisive financial innovation (e.g. bills of exchange,[21] double-entry bookkeeping system) to medieval fairs. This period also saw the eclipse of Florence's formerly powerful rival Pisa.[22] The growing power of the merchant elite culminated in an anti-aristocratic uprising, led by Giano della Bella, resulting in the Ordinances of Justice[23] which entrenched the power of the elite guilds until the end of the Republic.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Rise of the Medici

At the height of demographic expansion around 1325, the urban population may have been as great as 120,000, and the rural population around the city was probably close to 300,000.[24] The Black Death of 1348 reduced it by over half.[25][26] About 25,000 are said to have been supported by the city's wool industry: in 1345 Florence was the scene of an attempted strike by wool combers (ciompi), who in 1378 rose up in a brief revolt against oligarchic rule in the Revolt of the Ciompi. After their suppression, Florence came under the sway (1382–1434) of the Albizzi family, who became bitter rivals of the Medici.

In the 15th century, Florence was among the largest cities in Europe, with a population of 60,000, and was considered rich and economically successful.[27] Cosimo de' Medici was the first Medici family member to essentially control the city from behind the scenes. Although the city was technically a democracy of sorts, his power came from a vast patronage network along with his alliance to the new immigrants, the gente nuova (new people). The fact that the Medici were bankers to the pope also contributed to their ascendancy. Cosimo was succeeded by his son Piero, who was, soon after, succeeded by Cosimo's grandson, Lorenzo in 1469. Lorenzo was a great patron of the arts, commissioning works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli. Lorenzo was an accomplished poet and musician and brought composers and singers to Florence, including Alexander Agricola, Johannes Ghiselin, and Heinrich Isaac. By contemporary Florentines (and since), he was known as "Lorenzo the Magnificent" (Lorenzo il Magnifico).

Following Lorenzo de' Medici's death in 1492, he was succeeded by his son Piero II. When the French king Charles VIII invaded northern Italy, Piero II chose to resist his army. But when he realised the size of the French army at the gates of Pisa, he had to accept the humiliating conditions of the French king. These made the Florentines rebel, and they expelled Piero II. With his exile in 1494, the first period of Medici rule ended with the restoration of a republican government.

Savonarola, Machiavelli, and the Medici popes

During this period, the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola had become prior of the San Marco monastery in 1490. He was famed for his penitential sermons, lambasting what he viewed as widespread immorality and attachment to material riches. He praised the exile of the Medici as the work of God, punishing them for their decadence. He seized the opportunity to carry through political reforms leading to a more democratic rule. But when Savonarola publicly accused Pope Alexander VI of corruption, he was banned from speaking in public. When he broke this ban, he was excommunicated. The Florentines, tired of his teachings, turned against him and arrested him. He was convicted as a heretic, hanged and burned on the Piazza della Signoria on 23 May 1498. His ashes were dispersed in the Arno river.[28]

Another Florentine of this period was Niccolò Machiavelli, whose prescriptions for Florence's regeneration under strong leadership have often been seen as a legitimization of political expediency and even malpractice. Machiavelli was a political thinker, renowned for his political handbook The Prince, which is about ruling and exercising power. Commissioned by the Medici, Machiavelli also wrote the Florentine Histories, the history of the city.

In 1512, the Medici retook control of Florence with the help of Spanish and Papal troops.[29] They were led by two cousins, Giovanni and Giulio de' Medici, both of whom would later become Popes of the Catholic Church, (Leo X and Clement VII, respectively). Both were generous patrons of the arts, commissioning works like Michelangelo's Laurentian Library and Medici Chapel in Florence, to name just two.[30][31] Their reigns coincided with political upheaval in Italy, and thus in 1527, Florentines drove out the Medici for a second time and re-established a theocratic republic on 16 May 1527, (Jesus Christ was named King of Florence).[32] The Medici returned to power in Florence in 1530, with the armies of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and the blessings of Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici).

Florence officially became a monarchy in 1531, when Emperor Charles and Pope Clement named Alessandro de' Medici as Duke of the Florentine Republic. The Medici's monarchy would last over two centuries. Alessandro's successor, Cosimo I de' Medici, was named Grand Duke of Tuscany in 1569; in all Tuscany, only the Republic of Lucca (later a Duchy) and the Principality of Piombino were independent from Florence.

18th and 19th centuries

The extinction of the Medici dynasty and the accession in 1737 of Francis Stephen, duke of Lorraine and husband of Maria Theresa of Austria, led to Tuscany's temporary inclusion in the territories of the Austrian crown. It became a secundogeniture of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty, who were deposed for the House of Bourbon-Parma in 1801. From 1801 to 1807 Florence was the capital of the Napoleonic client state Kingdom of Etruria. The Bourbon-Parma were deposed in December 1807 when Tuscany was annexed by France. Florence was the prefecture of the French département of Arno from 1808 to the fall of Napoleon in 1814. The Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty was restored on the throne of Tuscany at the Congress of Vienna but finally deposed in 1859. Tuscany became a region of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

Florence replaced Turin as Italy's capital in 1865 and, in an effort to modernise the city, the old market in the Piazza del Mercato Vecchio and many medieval houses were pulled down and replaced by a more formal street plan with newer houses. The Piazza (first renamed Piazza Vittorio Emanuele II, then Piazza della Repubblica, the present name) was significantly widened and a large triumphal arch was constructed at the west end. A museum recording the destruction stands nearby today.

The country's second capital city was superseded by Rome six years later, after the withdrawal of the French troops allowed the capture of Rome.

20th century

During World War II the city experienced a year-long German occupation (1943–1944) being part of the Italian Social Republic. Hitler declared it an open city on 3 July 1944 as troops of the British 8th Army closed in.[33] Except for the Ponte Vecchio,[34] in early August, the retreating Germans decided to demolish all the bridges along the Arno linking the district of Oltrarno to the rest of the city, making it difficult for troops of the 8th Army to cross.

Florence was liberated by New Zealand, South African and British troops on 4 August 1944 alongside partisans from the Tuscan Committee of National Liberation (CTLN). The Allied soldiers who died driving the Germans from Tuscany are buried in cemeteries outside the city (Americans about nine kilometres or 5+1⁄2 miles south of the city, British and Commonwealth soldiers a few kilometres east of the centre on the right bank of the Arno).

At the end of World War II in May 1945, the US Army's Information and Educational Branch was ordered to establish an overseas university campus for demobilised American service men and women in Florence. The first American university for service personnel was established in June 1945 at the School of Aeronautics. Some 7,500 soldier-students were to pass through the university during its four one-month sessions (see G. I. American Universities).[35]

In November 1966, the Arno flooded parts of the centre, damaging many art treasures. Around the city there are tiny placards on the walls noting where the flood waters reached at their highest point.

Geography

Florence lies in a basin formed by the hills of Careggi, Fiesole, Settignano, Arcetri, Poggio Imperiale and Bellosguardo (Florence). The Arno river, three other minor rivers (Mugnone,[36] Ema and Greve) and some streams flow through it.[37]

Climate

Florence has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa), tending to Mediterranean (Csa).[38] It has hot summers with moderate or light rainfall and cool, damp winters. As Florence lacks a prevailing wind, summer temperatures are higher than along the coast. Rainfall in summer is convectional, while relief rainfall dominates in the winter. Snow is rare.[39] The highest officially recorded temperature was 42.6 °C (108.7 °F) on 26 July 1983 and the lowest was −23.2 °C (−9.8 °F) on 12 January 1985.[40]

| Climate data for Florence (Florence Airport) (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.7 (83.7) |

33.8 (92.8) |

41.8 (107.2) |

42.6 (108.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

36.4 (97.5) |

30.8 (87.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

42.6 (108.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.2 (52.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.1 (84.4) |

32.3 (90.1) |

32.4 (90.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

21.2 (70.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.6 (36.7) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −23.2 (−9.8) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−23.2 (−9.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.1 (2.29) |

63.8 (2.51) |

61.4 (2.42) |

67.2 (2.65) |

63.0 (2.48) |

44.8 (1.76) |

24.6 (0.97) |

36.5 (1.44) |

66.8 (2.63) |

105.1 (4.14) |

115.3 (4.54) |

81.4 (3.20) |

788 (31.03) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.5 | 7.2 | 7.0 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 5.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 6.2 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 9.6 | 84.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.5 | 67.3 | 64.6 | 64.7 | 64.9 | 62.9 | 60.6 | 60.5 | 64.4 | 70.5 | 74.6 | 74.1 | 66.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 33 | 40 | 42 | 46 | 53 | 60 | 67 | 64 | 58 | 45 | 30 | 33 | 48 |

| Source 1: NOAA[41] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Servizio Meteorologico[42] Weather Atlas[43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Florence | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 9.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.1 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4.4 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[44] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1200 | 50,000 | — |

| 1300 | 120,000 | +140.0% |

| 1500 | 70,000 | −41.7% |

| 1650 | 70,000 | +0.0% |

| 1861 | 150,864 | +115.5% |

| 1871 | 201,138 | +33.3% |

| 1881 | 196,072 | −2.5% |

| 1901 | 236,635 | +20.7% |

| 1911 | 258,056 | +9.1% |

| 1921 | 280,133 | +8.6% |

| 1931 | 304,160 | +8.6% |

| 1936 | 321,176 | +5.6% |

| 1951 | 374,625 | +16.6% |

| 1961 | 436,516 | +16.5% |

| 1971 | 457,803 | +4.9% |

| 1981 | 448,331 | −2.1% |

| 1991 | 403,294 | −10.0% |

| 2001 | 356,118 | −11.7% |

| 2011 | 358,079 | +0.6% |

| 2021 | 361,619 | +1.0% |

| Source: ISTAT 2021 | ||

In 1200 the city was home to 50,000 people.[45] By 1300 the population of the city proper was 120,000, with an additional 300,000 living in the Contado.[46] Between 1500 and 1650 the population was around 70,000.[47][48]

As of 31 October 2010[update], the population of the city proper is 370,702, while Eurostat estimates that 696,767 people live in the urban area of Florence. The Metropolitan Area of Florence, Prato and Pistoia, constituted in 2000 over an area of roughly 4,800 square kilometres (1,850 sq mi), is home to 1.5 million people. Within Florence proper, 46.8% of the population was male in 2007 and 53.2% were female. Minors (children aged 18 and less) totalled 14.10% of the population compared to pensioners, who numbered 25.95 percent. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06 percent (minors) and 19.94 percent (pensioners). The average age of Florence resident is 49 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Florence grew by 3.22 percent, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.56 percent.[49] The birth rate of Florence is 7.66 births per 1,000 inhabitants compared to the Italian average of 9.45 births.

As of 2009[update], 87.46% of the population was Italian. An estimated 6,000 Chinese live in the city.[50] The largest immigrant group came from other European countries (mostly Romanians and Albanians): 3.52%, East Asia (mostly Chinese and Filipino): 2.17%, the Americas: 1.41%, and North Africa (mostly Moroccan): 0.9%.[51]

Much like the rest of Italy most of the people in Florence are Roman Catholic, with more than 90% of the population belonging to the Archdiocese of Florence.[52][53]

As of 2016, an estimated 30,000 people, or 8% of the population, identified as Muslim.[54]

Foreign-born population (31.12.2019)

| # | Country | Population |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8,461 | |

| 2 | 6,409 | |

| 3 | 5,910 | |

| 4 | 5,108 | |

| 5 | 4,939 | |

| 6 | 2,541 | |

| 7 | 1,942 | |

| 8 | 1,801 | |

| 9 | 1,418 | |

| 10 | 1,175 | |

| 11 | 1,137 | |

| 12 | 1,037 | |

| 13 | 965 |

Economy

Tourism is, by far, the most important of all industries and most of the Florentine economy relies on the money generated by international arrivals and students studying in the city.[11] The value tourism to the city totalled some €2.5 billion in 2015 and the number of visitors had increased by 5.5% from the previous year.[55]

In 2013, Florence was listed as the second best world city by Condé Nast Traveler.[56]

Manufacturing and commerce remain highly important. Florence is Italy's 17th richest city in terms of average workers' earnings, with the figure being €23,265 (the overall city's income is €6,531,204,473), coming after Mantua, yet surpassing Bolzano.[57]

Industry, commerce and services

Florence is a major production and commercial centre in Italy, where the Florentine industrial complexes in the suburbs produce all sorts of goods, from furniture, rubber goods, chemicals, and food.[11] Traditional and local products, such as antiques, handicrafts, glassware, leatherwork, art reproductions, jewellery, souvenirs, elaborate metal and iron-work, shoes, accessories and high fashion clothes also occupy a fair sector of Florence's economy.[11] The city's income relies partially on services and commercial and cultural interests, such as annual fairs, theatrical and lyrical productions, art exhibitions, festivals and fashion shows, such as the Calcio Fiorentino. Heavy industry and machinery also take their part in providing an income. In Nuovo Pignone, numerous factories are still present, and small-to medium industrial businesses are dominant. The Florence-Prato-Pistoia industrial districts and areas were known as the 'Third Italy' in the 1990s, due to the exports of high-quality goods and automobile (especially the Vespa) and the prosperity and productivity of the Florentine entrepreneurs. Some of these industries even rivalled the traditional industrial districts in Emilia-Romagna and Veneto due to high profits and productivity.[11]

In the fourth quarter of 2015, manufacturing increased by 2.4% and exports increased by 7.2%. Leading sectors included mechanical engineering, fashion, pharmaceutics, food and wine. During 2015, permanent employment contracts increased by 48.8 percent, boosted by nationwide tax break.[55]

Tourism

Tourism is the most significant industry in central Florence. From April to October, tourists outnumber the local population. Tickets to the Uffizi and Accademia galleries are regularly sold out and large groups regularly fill the basilicas of Santa Croce and Santa Maria Novella, both of which charge for entry. Tickets for The Uffizi and Accademia can be purchased online prior to visiting.[58] In 2010, readers of Travel + Leisure magazine ranked the city as their third favourite tourist destination.[59] In 2015, Condé Nast Travel readers voted Florence as the best city in Europe.[60]

Studies by Euromonitor International have concluded that cultural and history-oriented tourism is generating significantly increased spending throughout Europe.[61]

Florence is believed to have the greatest concentration of art (in proportion to its size) in the world.[62] Thus, cultural tourism is particularly strong, with world-renowned museums such as the Uffizi selling over 1.93 million tickets in 2014.[63] The city's convention centre facilities were restructured during the 1990s and host exhibitions, conferences, meetings, social forums, concerts and other events.

In 2016, Florence had 20,588 hotel rooms in 570 facilities. International visitors use 75% of the rooms; some 18% of those were from the U.S.[64] In 2014, the city had 8.5 million overnight stays.[65] A Euromonitor report indicates that in 2015 the city ranked as the world's 36th most visited in the world, with over 4.95 million arrivals for the year.[66]

Tourism brings revenue to Florence, but also creates certain problems. The Ponte Vecchio, The San Lorenzo Market and Santa Maria Novella are plagued by pickpockets.[67] The province of Florence receives roughly 13 million visitors per year[68] and in peak seasons, popular locations may become overcrowded as a result.[69] In 2015, Mayor Dario Nardella expressed concern over visitors who arrive on buses, stay only a few hours, spend little money but contribute significantly to overcrowding. "No museum visit, just a photo from the square, the bus back and then on to Venice ... We don't want tourists like that", he said.[70]

Some tourists are less than respectful of the city's cultural heritage, according to Nardella. In June 2017, he instituted a programme of spraying church steps with water to prevent tourists from using such areas as picnic spots. While he values the benefits of tourism, he claims that there has been "an increase among those who sit down on church steps, eat their food and leave rubbish strewn on them", he explained.[71] To boost the sale of traditional foods, the mayor had introduced legislation (enacted in 2016) that requires restaurants to use typical Tuscan products and rejected McDonald's application to open a location in the Piazza del Duomo.[72]

In October 2021, Florence was shortlisted for the European Commission's 2022 European Capital of Smart Tourism award along with Bordeaux, Copenhagen, Dublin, Ljubljana, Palma de Mallorca and Valencia.[73]

Food and wine production

Food and wine have long been an important staple of the economy. The Chianti region is just south of the city, and its Sangiovese grapes figure prominently not only in its Chianti Classico wines but also in many of the more recently developed Supertuscan blends. Within 32 km (20 mi) to the west is the Carmignano area, also home to flavourful sangiovese-based reds. The celebrated Chianti Rufina district, geographically and historically separated from the main Chianti region, is also few kilometres east of Florence. More recently, the Bolgheri region (about 150 km or 93 mi southwest of Florence) has become celebrated for its "Super Tuscan" reds such as Sassicaia and Ornellaia.[74]

Government

-

The traditional boroughs of the whole comune of Florence

-

The 5 administrative boroughs of the whole comune of Florence

The legislative body of the municipality is the City Council (Consiglio Comunale), which is composed of 36 councillors elected every five years with a proportional system, at the same time as the mayoral elections. The executive body is the City Committee (Giunta Comunale), composed of 7 assessors, nominated and presided over by a directly elected Mayor. The current mayor of Florence is Sara Funaro.

The municipality of Florence is subdivided into five administrative Boroughs (Quartieri). Each borough is governed by a Council (Consiglio) and a President, elected at the same time as the city mayor. The urban organisation is governed by the Italian Constitution (art. 114). The boroughs have the power to advise the Mayor with nonbinding opinions on a large spectrum of topics (environment, construction, public health, local markets) and exercise the functions delegated to them by the City Council; in addition they are supplied with an autonomous funding in order to finance local activities. The boroughs are:

- Q1 – Centro storico (Historic Centre); population: 67,170;

- Q2 – Campo di Marte; population: 88,588;

- Q3 – Gavinana-Galluzzo; population: 40,907;

- Q4 – Isolotto-Legnaia; population: 66,636;

- Q5 – Rifredi; population: 103,761.

All of the five boroughs are governed by the Democratic Party.

The former Italian Prime Minister (2014–2016), Matteo Renzi, served as mayor from 2009 to 2014.

Culture

Art

Florence was the birthplace of High Renaissance art, which lasted from about 1500 to 1527. Renaissance art put a larger emphasis on naturalism and human emotion.[75] Medieval art was often formulaic and symbolic; the surviving works are mostly religious, their subjects were chosen by clerics. By contrast, Renaissance art became more rational, mathematical, individualistic,[75] and was produced by known artists such as Donatello, Michelangelo, and Raphael, who started to sign their works. Religion was important, but with this new age came the humanization[76][77] of religious figures in art, such as in Masaccio's Expulsion from the Garden of Eden and Raphael's Madonna della Seggiola; people of this age began to understand themselves as human beings, which reflected in art.[77] The Renaissance marked the rebirth of classical values in art and society as people studied the ancient masters of the Greco-Roman world;[76] art became focused on realism as opposed to idealism.[77]

Cimabue and Giotto, the fathers of Italian painting, lived in Florence, as did Arnolfo di Cambio and Andrea Pisano, renewers of architecture and sculpture; Filippo Brunelleschi, Donatello and Masaccio, forefathers of the Renaissance, Lorenzo Ghiberti and the Della Robbia family, Filippo Lippi and Fra Angelico; Sandro Botticelli, Paolo Uccello and the universal genius of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.[78][79]

Their works, together with those of many other generations of artists, are gathered in the city's many museums: the Uffizi Gallery, the Galleria Palatina with the paintings of the "Golden Ages",[80] the Bargello with the sculptures of the Renaissance, the museum of San Marco with Fra Angelico's works, the Galleria dell'Accademia, the Medici Chapels,[81] the museum of Orsanmichele, the Casa Buonarroti with sculptures by Michelangelo, the Museo Bardini, the Museo Horne, the Museo Stibbert, the Palazzo Corsini, the Galleria d'Arte Moderna, the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, the Tesoro dei Granduchi and the Museo dell'Opificio delle Pietre Dure.[82] Several monuments are located in Florence: the Baptistery with its mosaics; the cathedral with its sculptures, the medieval churches with bands of frescoes; public as well as private palaces – the Palazzo Vecchio, the Palazzo Pitti, the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, the Palazzo Davanzati and the Casa Martelli; monasteries, cloisters, refectories; the Certosa. The Museo Archeologico Nazionale documents Etruscan civilization.[83] The city is so rich in art that some visitors experience Stendhal syndrome as they encounter its art for the first time.[84]

Florentine architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1466) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472) were among the fathers of Renaissance architecture.[85] The cathedral, topped by Brunelleschi's dome, dominates the Florentine skyline. The Florentines decided to start building it late in the 13th century, without a design for the dome. The project proposed by Brunelleschi in the 14th century was the largest ever built at the time, and the first major dome built in Europe since the two great domes of Roman times – the Pantheon in Rome, and Hagia Sophia in Constantinople. The dome of Santa Maria del Fiore remains the largest brick construction of its kind in the world.[86][87] In front of it is the medieval Baptistery. The two buildings incorporate in their decoration the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. In recent years, most of the important works of art from the two buildings – and from the nearby Giotto's Campanile, have been removed and replaced by copies. The originals are now housed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, just to the east of the cathedral.

Florence has a large number of art-filled churches, such as San Miniato al Monte, San Lorenzo, Santa Maria Novella, Santa Trinita, Santa Maria del Carmine, Santa Croce, Santo Spirito, Santissima Annunziata, Ognissanti and numerous others.[11]

Artists associated with Florence range from Arnolfo di Cambio and Cimabue to Giotto, Nanni di Banco, and Paolo Uccello; through Lorenzo Ghiberti, and Donatello and Masaccio and the della Robbia family; through Fra Angelico and Sandro Botticelli and Piero della Francesca, and on to Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo. Others include Benvenuto Cellini, Andrea del Sarto, Benozzo Gozzoli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Filippo Lippi, Bernardo Buontalenti, Orcagna, Antonio and Piero del Pollaiuolo, Filippino Lippi, Andrea del Verrocchio, Bronzino, Desiderio da Settignano, Michelozzo, Cosimo Rosselli, the Sangallos, and Pontormo. Artists from other regions who worked in Florence include Raphael, Andrea Pisano, Giambologna, Il Sodoma and Peter Paul Rubens.

Picture galleries in Florence include the Uffizi and the Palazzo Pitti. Two superb collections of sculpture are in the Bargello and the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. They are filled with the creations of Donatello, Verrocchio, Desiderio da Settignano, Michelangelo and others. The Galleria dell'Accademia has Michelangelo's David, which was created between 1501 and 1504 and is perhaps the best-known work of art anywhere, plus the unfinished statues of slaves Michelangelo created for the tomb of Pope Julius II.[88][89] Other sights include the medieval city hall, the Palazzo della Signoria (also known as the Palazzo Vecchio), the National Archeological Museum, the Museo Galileo, the Palazzo Davanzati, the Museo Stibbert, the Museo Nazionale di San Marco, the Medici Chapels, the Museo dell'Opera di Santa Croce, the Museum of the Cloister of Santa Maria Novella, the Zoological Museum ("La Specola"), the Museo Bardini, and the Museo Horne. There is also a collection of works by the modern sculptor, Marino Marini, in a museum named after him. The Palazzo Strozzi is the site of special exhibitions.[90]

Language

Florentine (fiorentino), spoken by inhabitants of Florence and its environs, is a Tuscan dialect and the immediate parent language to modern Italian.

Although its vocabulary and pronunciation are largely identical to standard Italian, differences do exist. The Vocabolario del fiorentino contemporaneo (Dictionary of Modern Florentine) reveals lexical distinctions from all walks of life.[91]

Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio pioneered the use of the vernacular[92] instead of the Latin used for most literary works at the time.

Literature

Despite Latin being the main language of the courts and the Church in the Middle Ages, writers such as Dante Alighieri[92] and many others used their own language, the Florentine vernacular descended from Latin, in composing their greatest works. The oldest literary pieces written in Florentine go as far back as the 13th century. Florence's literature fully blossomed in the 14th century, when not only Dante with his Divine Comedy (1306–1321) and Petrarch, but also poets such as Guido Cavalcanti and Lapo Gianni composed their most important works.[92] Dante's masterpiece is the Divine Comedy, which mainly deals with the poet himself taking an allegoric and moral tour of Hell, Purgatory and finally Heaven, during which he meets numerous mythological or real characters of his age or before. He is first guided by the Roman poet Virgil, whose non-Christian beliefs damned him to Hell. Later on he is joined by Beatrice, who guides him through Heaven.[92]

In the 14th century, Petrarch[93] and Giovanni Boccaccio[93] led the literary scene in Florence after Dante's death in 1321. Petrarch was an all-rounder writer, author and poet, but was particularly known for his Canzoniere, or the Book of Songs, where he conveyed his unremitting love for Laura.[93] His style of writing has since become known as Petrarchism.[93] Boccaccio was better known for his Decameron, a slightly grim story of Florence during the 1350s bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, when some people fled the ravaged city to an isolated country mansion, and spent their time there recounting stories and novellas taken from the medieval and contemporary tradition. All of this is written in a series of 100 distinct novellas.[93]

In the 16th century, during the Renaissance, Florence was the home town of political writer and philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli, whose ideas on how rulers should govern the land, detailed in The Prince, spread across European courts and enjoyed enduring popularity for centuries. These principles became known as Machiavellianism.

Music

Florence became a musical centre during the Middle Ages and music and the performing arts remain an important part of its culture. The growth of Northern Italian Cities in the 1500s likely contributed to its increased prominence. During the Renaissance, there were four kinds of musical patronage in the city with respect to both sacred and secular music: state, corporate, church, and private. It was here that the Florentine Camerata convened in the mid-16th century and experimented with setting tales of Greek mythology to music and staging the result—in other words, the first operas, setting the wheels in motion not just for the further development of the operatic form, but for later developments of separate "classical" forms such as the symphony and concerto. After the year 1600, Italian trends prevailed across Europe, by 1750 it was the primary musical language. The genre of the Madrigal, born in Italy, gained popularity in Britain and elsewhere. Several Italian cities were "larger on the musical map than their real-size for power suggested. Florence, was once such city which experienced a fantastic period in the early seventeenth Century of musico-theatrical innovation, including the beginning and flourishing of opera.[94]

Opera was invented in Florence in the late 16th century when Jacopo Peri's Dafne an opera in the style of monody, was premiered. Opera spread from Florence throughout Italy and eventually Europe. Vocal Music in the choir setting was also taking new identity at this time. At the beginning of the 17th century, two practices for writing music were devised, one the first practice or Stile Antico/Prima Prattica the other the Stile Moderno/Seconda Prattica. The Stile Antico was more prevalent in Northern Europe and Stile Moderno was practiced more by the Italian Composers of the time.[95] The piano was invented in Florence in 1709 by Bartolomeo Cristofori. Composers and musicians who have lived in Florence include Piero Strozzi (1550 – after 1608), Giulio Caccini (1551–1618) and Mike Francis (1961–2009). Giulio Caccini's book Le Nuove Musiche was significant in performance practice technique instruction at the time.[94] The book specified a new term, in use by the 1630s, called monody which indicated the combination of voice and basso continuo and connoted a practice of stating text in a free, lyrical, yet speech-like manner. This would occur while an instrument, usually a keyboard type such as harpsichord, played and held chords while the singer sang/spoke the monodic line.[96]

Cinema

Florence has been a setting for numerous works of fiction and movies, including the novels and associated films, such as Light in the Piazza, The Girl Who Couldn't Say No, Calmi Cuori Appassionati, Hannibal, A Room with a View, Tea with Mussolini, Virgin Territory and Inferno. The city is home to renowned Italian actors and actresses, such as Roberto Benigni, Leonardo Pieraccioni and Vittoria Puccini.

Video games

Florence has appeared as a location in video games such as Assassin's Creed II.[97] The Republic of Florence also appears as a playable nation in Paradox Interactive's grand strategy game Europa Universalis IV.

Other media

16th century Florence is the setting of the Japanese manga and anime series Arte.

Cuisine

Florentine food grows out of a tradition of peasant fare rather than rarefied high cuisine. The majority of dishes are based on meat. The whole animal was traditionally eaten; tripe (trippa) and stomach (lampredotto) were once regularly on the menu at restaurants and still are sold at the food carts stationed throughout the city. Antipasti include crostini toscani, sliced bread rounds topped with a chicken liver-based pâté, and sliced meats (mainly prosciutto and salame, often served with melon when in season). The typically saltless Tuscan bread, obtained with natural levain frequently features in Florentine courses, especially in its soups, ribollita and pappa al pomodoro, or in the salad of bread and fresh vegetables called panzanella that is served in summer. The bistecca alla fiorentina is a large (the customary size should weigh around 1.2 to 1.5 kg or 2 lb 10 oz to 3 lb 5 oz) – the "date" steak – T-bone steak of Chianina beef cooked over hot charcoal and served very rare with its more recently derived version, the tagliata, sliced rare beef served on a bed of arugula, often with slices of Parmesan cheese on top. Most of these courses are generally served with local olive oil, also a prime product enjoying a worldwide reputation.[98]

Among the desserts, schiacciata alla fiorentina, a white flatbread cake, is one of the most popular; it is a very soft cake, prepared with extremely simple ingredients, typical of Florentine cuisine, and is especially eaten at Carnival.

Research activity

Research institutes and university departments are located within the Florence area and within two campuses at Polo di Novoli and Polo Scientifico di Sesto Fiorentino[99] as well as in the Research Area of Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche.[100]

Science and discovery

Florence has been an important scientific centre for centuries, notably during the Renaissance with scientists such as Leonardo da Vinci.

Florentines were one of the driving forces behind the Age of Discovery. Florentine bankers financed Henry the Navigator and the Portuguese explorers who pioneered the route around Africa to India and the Far East. It was a map drawn by the Florentine Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, a student of Brunelleschi, that Christopher Columbus used to sell his "enterprise" to the Spanish monarchs, and which he used on his first voyage. Mercator's "Projection" is a refined version of Toscanelli's, taking the Americas into account.

Galileo and other scientists pioneered the study of optics, ballistics, astronomy, anatomy, and other scientific disciplines. Pico della Mirandola, Leonardo Bruni, Machiavelli, and many others laid the groundwork for modern scientific understanding.

Fashion

By the year 1300 Florence had become a centre of textile production in Europe. Many of the rich families in Renaissance Florence were major purchasers of locally produced fine clothing, and the specialists of fashion in the economy and culture of Florence during that period is often underestimated.[101] Florence is regarded by some as the birthplace and earliest centre of the modern (post World War Two) fashion industry in Italy. The Florentine "soirées" of the early 1950s organised by Giovanni Battista Giorgini were events where several Italian designers participated in group shows and first garnered international attention.[102] Florence has served as the home of the Italian fashion company Salvatore Ferragamo since 1928. Gucci, Roberto Cavalli, and Emilio Pucci are also headquartered in Florence. Other major players in the fashion industry such as Prada and Chanel have large offices and stores in Florence or its outskirts. Florence's main upscale shopping street is Via de' Tornabuoni, where major luxury fashion houses and jewellery labels, such as Armani and Bulgari, have boutiques. Via del Parione and Via Roma are other streets that are also well known for their high-end fashion stores.[103]

Historical evocations

Scoppio del Carro

The Scoppio del Carro ("Explosion of the Cart") is a celebration of the First Crusade. During the day of Easter, a cart, which the Florentines call the Brindellone and which is led by four white oxen, is taken to the Piazza del Duomo between the Baptistery of St. John the Baptist (Battistero di San Giovanni) and the Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore). The cart is connected by a rope to the interior of the church. Near the cart there is a model of a dove, which, according to legend, is a symbol of good luck for the city: at the end of the Easter mass, the dove emerges from the nave of the Duomo and ignites the fireworks on the cart.

Calcio Storico

Calcio Storico Fiorentino ("Historic Florentine Football"), sometimes called Calcio in costume, is a traditional sport, regarded as a forerunner of soccer, though the actual gameplay most closely resembles rugby. The event originates from the Middle Ages, when the most important Florentine nobles amused themselves playing while wearing bright costumes. The most important match was played on 17 February 1530, during the siege of Florence. That day Papal troops besieged the city while the Florentines, with contempt of the enemies, decided to play the game notwithstanding the situation. The game is played in the Piazza di Santa Croce. A temporary arena is constructed, with bleachers and a sand-covered playing field. A series of matches are held between four teams representing each quartiere (quarter) of Florence during late June and early July.[104] There are four teams: Azzurri (light blue), Bianchi (white), Rossi (red) and Verdi (green). The Azzurri are from the quarter of Santa Croce, Bianchi from the quarter of Santo Spirito, Verdi are from San Giovanni and Rossi from Santa Maria Novella.

Main sights

Florence is known as the "cradle of the Renaissance" (la culla del Rinascimento) for its monuments, churches, and buildings. The best-known site of Florence is the domed cathedral of the city, Santa Maria del Fiore, known as The Duomo, whose dome was built by Filippo Brunelleschi. The nearby Campanile (partly designed by Giotto) and the Baptistery buildings are also highlights. The dome, 600 years after its completion, is still the largest dome built in brick and mortar in the world.[105] In 1982, the historic centre of Florence (Italian: centro storico di Firenze) was declared a World Heritage Site by the UNESCO.[106] The centre of the city is contained in medieval walls that were built in the 14th century to defend the city. At the heart of the city, in Piazza della Signoria, is Bartolomeo Ammannati's Fountain of Neptune (1563–1565), which is a masterpiece of marble sculpture at the terminus of a still functioning Roman aqueduct.

The layout and structure of Florence in many ways harkens back to the Roman era, where it was designed as a garrison settlement.[11] Nevertheless, the majority of the city was built during the Renaissance.[11] Despite the strong presence of Renaissance architecture within the city, traces of medieval, Baroque, Neoclassical and modern architecture can be found. The Palazzo Vecchio as well as the Duomo, or the city's Cathedral, are the two buildings which dominate Florence's skyline.[11]

The river (Arno), which cuts through the old part of the city, is as much a character in Florentine history as many of the people who lived there. Historically, the locals have had a love-hate relationship with the Arno – which alternated between nourishing the city with commerce, and destroying it by flood.

One of the bridges in particular stands out – the Ponte Vecchio ('Old Bridge'), whose most striking feature is the multitude of shops built upon its edges, held up by stilts. The bridge also carries Vasari's elevated corridor linking the Uffizi to the Medici residence (Palazzo Pitti). Although the original bridge was constructed by the Etruscans, the current bridge was rebuilt in the 14th century. It is the only bridge in the city to have survived World War II intact. It is the first example in the western world of a bridge built using segmental arches, that is, arches less than a semicircle, to reduce both span-to-rise ratio and the numbers of pillars to allow lesser encumbrance in the riverbed (being in this much more successful than the Roman Alconétar Bridge).

The church of San Lorenzo contains the Medici Chapels, a complex of burial chapels of the Medici family—the most powerful family in Florence from the 15th to the 18th centuries.

The Uffizi Gallery, one of the finest art museums in the world, was founded on a large bequest from the last member of the Medici family. It is located at the corner of Piazza della Signoria, a site important for being the centre of Florence's civil life and government for centuries. The Palazzo della Signoria facing it is still home of the municipal government. Many significant episodes in the history of art and political changes were staged here, such as:

- In 1301, Dante Alighieri was sent into exile from here (commemorated by a plaque on one of the walls of the Uffizi).

- On 26 April 1478, Jacopo de' Pazzi and his retainers tried to raise the city against the Medici after the plot known as La congiura dei Pazzi (The Pazzi conspiracy), murdering Giuliano di Piero de' Medici and wounding his brother Lorenzo. All the members of the plot who could be apprehended were seized by the Florentines and hanged from the windows of the palace.

- In 1497, it was the location of the Bonfire of the vanities instigated by the Dominican friar and preacher Girolamo Savonarola.

- On 23 May 1498, the same Savonarola and two followers were hanged and burnt at the stake. (A round plate in the ground marks the spot where he was hanged)

- In 1504, Michelangelo's David (now replaced by a replica, since the original was moved in 1873 to the Galleria dell'Accademia) was installed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria (also known as Palazzo Vecchio).

The Loggia dei Lanzi in Piazza della Signoria is the location of a number of statues by other sculptors such as Donatello, Giambologna, Bartolomeo Ammannati and Benvenuto Cellini, although some have been replaced with copies to preserve the originals.

-

Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore

-

1835 City Map of Florence, still largely in the confines of its medieval city centre

-

Ponte Vecchio, which spans the Arno river

-

Florence at night from Piazzale Michelangelo

-

Ponte Santa Trinita with the Oltrarno district

-

The city of Florence as seen from the hill of Fiesole

-

Florence Duomo as seen from Michelangelo hill

Monuments, museums and religious buildings

Florence contains several palaces and buildings from various eras. The Palazzo Vecchio is the town hall of Florence and also an art museum. This large Romanesque crenellated fortress-palace overlooks the Piazza della Signoria with its copy of Michelangelo's David statue as well as the gallery of statues in the adjacent Loggia dei Lanzi. Originally called the Palazzo della Signoria, after the Signoria of Florence, the ruling body of the Republic of Florence, it was also given several other names: Palazzo del Popolo, Palazzo dei Priori, and Palazzo Ducale, in accordance with the varying use of the palace during its long history. The building acquired its current name when the Medici duke's residence was moved across the Arno to the Palazzo Pitti. It is linked to the Uffizi and the Palazzo Pitti through the Corridoio Vasariano.

Palazzo Medici Riccardi, designed by Michelozzo di Bartolomeo for Cosimo il Vecchio, of the Medici family, is another major edifice, and was built between 1445 and 1460. It was well known for its stone masonry that includes rustication and ashlar. Today it is the head office of the Metropolitan City of Florence and hosts museums and the Riccardiana Library. The Palazzo Strozzi, an example of civil architecture with its rusticated stone, was inspired by the Palazzo Medici, but with more harmonious proportions. Today the palace is used for international expositions like the annual antique show (founded as the Biennale dell'Antiquariato in 1959), fashion shows and other cultural and artistic events. Here also is the seat of the Istituto Nazionale del Rinascimento and the noted Gabinetto Vieusseux, with the library and reading room.

There are several other notable places, including the Palazzo Rucellai, designed by Leon Battista Alberti between 1446 and 1451 and executed, at least in part, by Bernardo Rossellino; the Palazzo Davanzati, which houses the museum of the Old Florentine House; the Palazzo delle Assicurazioni Generali, designed in the Neo-Renaissance style in 1871; the Palazzo Spini Feroni, in Piazza Santa Trinita, a historic 13th-century private palace, owned since the 1920s by shoe-designer Salvatore Ferragamo; as well as various others, including the Palazzo Borghese, the Palazzo di Bianca Cappello, the Palazzo Antinori, and the Royal building of Santa Maria Novella.[107]

Florence contains numerous museums and art galleries where some of the world's most important works of art are held. The city is one of the best preserved Renaissance centres of art and architecture in the world and has a high concentration of art, architecture and culture.[108] In the ranking list of the 15 most visited Italian art museums, ⅔ are represented by Florentine museums.[109] The Uffizi is one of these, having a very large collection of international and Florentine art. The gallery is articulated in many halls, catalogued by schools and chronological order. Engendered by the Medici family's artistic collections through the centuries, it houses works of art by various painters and artists. The Vasari Corridor is another gallery, built connecting the Palazzo Vecchio with the Pitti Palace passing by the Uffizi and over the Ponte Vecchio. The Galleria dell'Accademia houses a Michelangelo collection, including the David. It has a collection of Russian icons and works by various artists and painters. Other museums and galleries include the Bargello, which concentrates on sculpture works by artists including Donatello, Giambologna and Michelangelo; the Palazzo Pitti, containing part of the Medici family's former private collection. In addition to the Medici collection, the palace's galleries contain many Renaissance works, including several by Raphael and Titian, large collections of costumes, ceremonial carriages, silver, porcelain and a gallery of modern art dating from the 18th century. Adjoining the palace are the Boboli Gardens, elaborately landscaped and with numerous sculptures.

There are several different churches and religious buildings in Florence. The cathedral is Santa Maria del Fiore. The San Giovanni Baptistery located in front of the cathedral, is decorated by numerous artists, notably by Lorenzo Ghiberti with the Gates of Paradise. Other churches in Florence include the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella, located in Santa Maria Novella square (near the Firenze Santa Maria Novella railway station) which contains works by Masaccio, Paolo Uccello, Filippino Lippi and Domenico Ghirlandaio; the Basilica of Santa Croce, the principal Franciscan church in the city, which is situated on the Piazza di Santa Croce, about 800 metres (2,600 feet) southeast of the Duomo, and is the burial place of some of the most illustrious Italians, such as Michelangelo, Galileo, Machiavelli, Foscolo, Rossini, thus it is known also as the Temple of the Italian Glories (Tempio dell'Itale Glorie); the Basilica of San Lorenzo, which is one of the largest churches in the city, situated at the centre of Florence's main market district, and the burial place of all the principal members of the Medici family from Cosimo il Vecchio to Cosimo III; Santo Spirito, in the Oltrarno quarter, facing the square with the same name; Orsanmichele, whose building was constructed on the site of the kitchen garden of the monastery of San Michele, now demolished; Santissima Annunziata, a Roman Catholic basilica and the mother church of the Servite order; Ognissanti, which was founded by the lay order of the Umiliati, and is among the first examples of Baroque architecture built in the city; the Santa Maria del Carmine, in the Oltrarno district of Florence, which is the location of the Brancacci Chapel, housing outstanding Renaissance frescoes by Masaccio and Masolino da Panicale, later finished by Filippino Lippi; the Medici Chapel with statues by Michelangelo, in the San Lorenzo; as well as several others, including Santa Trinita, San Marco, Santa Felicita, Badia Fiorentina, San Gaetano, San Miniato al Monte, Florence Charterhouse, and Santa Maria del Carmine. The city additionally contains the Orthodox Russian church of Nativity, and the Great Synagogue of Florence, built in the 19th century.

Florence contains various theatres and cinemas. The Odeon Cinema of the Palazzo dello Strozzino is one of the oldest cinemas in the city. Established from 1920 to 1922[110] in a wing of the Palazzo dello Strozzino, it used to be called the Cinema Teatro Savoia (Savoy Cinema-Theatre), yet was later called Odeon. The Teatro della Pergola, located in the centre of the city on the eponymous street, is an opera house built in the 17th century. Another theatre is the Teatro Comunale (or Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino), originally built as the open-air amphitheatre, the Politeama Fiorentino Vittorio Emanuele, which was inaugurated on 17 May 1862 with a production of Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor and which seated 6,000 people. There are several other theatres, such as the Saloncino Castinelli, the Teatro Puccini, the Teatro Verdi, the Teatro Goldoni and the Teatro Niccolini.

Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore

Florence Cathedral, formally the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore, is the cathedral of Florence, Italy. It was begun in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was structurally completed by 1436, with the dome designed by Filippo Brunelleschi.

Squares, streets and parks

Aside from such monuments, Florence contains numerous major squares (piazze) and streets. The Piazza della Repubblica is a square in the city centre, location of the cultural cafés and bourgeois palaces. Among the square's cafés (like Caffè Gilli, Paszkowski or the Hard Rock Cafè), the Giubbe Rosse café has long been a meeting place for artists and writers, notably those of Futurism. The Piazza Santa Croce is another; dominated by the Basilica of Santa Croce, it is a rectangular square in the centre of the city where the Calcio Fiorentino is played every year. Furthermore, there is the Piazza Santa Trinita, a square near the Arno that mark the end of the Via de' Tornabuoni street.

Other squares include the Piazza San Marco, the Piazza Santa Maria Novella, the Piazza Beccaria and the Piazza della Libertà. The centre additionally contains several streets. Such include the Via Camillo Cavour, one of the main roads of the northern area of the historic centre; the Via Ghibellina, one of central Florence's longest streets; the Via dei Calzaiuoli, one of the most central streets of the historic centre which links Piazza del Duomo to Piazza della Signoria, winding parallel to via Roma and Piazza della Repubblica; the Via de' Tornabuoni, a luxurious street in the city centre that goes from Antinori square to ponte Santa Trinita, across Piazza Santa Trinita, characterised by the presence of fashion boutiques; the Viali di Circonvallazione, 6-lane boulevards surrounding the northern part of the historic centre; as well as others, such as Via Roma, Via degli Speziali, Via de' Cerretani, and the Viale dei Colli.

Florence also contains various parks and gardens. Such include the Boboli Gardens, the Parco delle Cascine, the Giardino Bardini and the Giardino dei Semplici, amongst others.

Sport

In association football, Florence is represented by ACF Fiorentina, which plays in Serie A, the top league of Italian league system. ACF Fiorentina has won two Italian Championships, in 1956 and 1969, and 6 Italian cups,[111] since their formation in 1926. They play their games at the Stadio Artemio Franchi, which holds 47,282. The women's team, ACF Fiorentina Femminile, have won the women's association football Italian Championship of the 2016–17 season.

The city is home of the Centro Tecnico Federale di Coverciano, in Coverciano, Florence, the main training ground of the Italian national team, and the technical department of the Italian Football Federation.

Florence was one of the host cities for cycling's 2013 UCI Road World Championships.[112][113] The city has also hosted stages of the Giro d'Italia, most recently in 2017.

Since 2017 Florence is also represented in Eccellenza, the top tier of rugby union league system in Italy, by I Medicei, which is a club established in 2015 by the merging of the senior squads of I Cavalieri (of Prato) and Firenze Rugby 1931. I Medicei won the Serie A Championship in 2016–17 and were promoted to Eccellenza for the 2017–18 season.

Rari Nantes Florentia is a successful water polo club based in Florence; both its male and female squads have won several Italian championships and the female squad has also European titles in their palmarès.

Transportation

Cars

The centre of Florence is closed to through-traffic, although buses, taxis and residents with appropriate permits are allowed in. This area is commonly referred to as the ZTL (Zona Traffico Limitato), which is divided into several subsections.[114] Residents of one section, therefore, will only be able to drive in their district and perhaps some surrounding ones. Cars without permits are allowed to enter after 7.30 pm, or before 7.30 am. The rules shift during the tourist-filled summers, putting more restrictions on where one can get in and out.[115]

Buses

ATAF&Li-nea was the bus company who run the principal public transit network in the city; it was one the companies of the consortium ONE Scarl[116] to accomplish the contract stipulated with the Regione Toscana for the public transport in the 2018–2019 period. Individual tickets, or a pass called Carta Agile with multiple rides, are purchased in advance and must be validated once on board. These tickets may be used on ATAF&Li-nea buses, Tramvia and second-class local trains only within city railway stations. The bus fleet consisted of 446 urban, 5 suburban, 20 intercity and 15 tourism buses.

Intercity bus transit is run by the SITA, COPIT, and CAP Autolinee companies. The transit companies also accommodate travellers from the Amerigo Vespucci Airport, which is 5 km (3 mi) west of the city centre, and which has scheduled services run by major European carriers.

Since 1 November 2021, the public local transport is operated by Autolinee Toscane.[117]

Trams

In an effort to reduce air pollution and car traffic in the city, a multi-line tram network called Tramvia is under construction. The first line began operation on 14 February 2010 and connects Florence's primary intercity railway station (Santa Maria Novella) with the southwestern suburb of Scandicci. This line is 7.4 km (4+5⁄8 mi) long and has 14 stops. The construction of a second line began on 5 November 2011, construction was stopped due to contractors' difficulties and restarted in 2014 with the new line opening on 11 February 2019. This second line connects Florence's airport with the city centre. A third line (from Santa Maria Novella to the Careggi area, where the most important hospitals of Florence are located) is also under construction.[118][119][120][circular reference]

Florence public transport statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Florence, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 59 min. 13% of public transit riders ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 14 min, while 22% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 4.1 km (2.5 mi), while 3% travel for over 12 km (7.5 mi) in a single direction.[121]

Airport

The Florence Airport, Peretola, is one of two main international airports in the Tuscany region. The other international airport in the Tuscany region is the Galileo Galilei International Airport in Pisa.

Railway station

Parts of this article (those related to the status of high-speed rail to Florence) need to be updated. (November 2023) |

Firenze Santa Maria Novella railway station is the main national and international railway station in Florence and is used by 59 million people every year.[122] The building, designed by Giovanni Michelucci, was built in the Italian Rationalism style and it is one of the major rationalist buildings in Italy. It is located in Piazza della Stazione, near the Fortezza da Basso, a masterpiece of the military Renaissance architecture, and the Viali di Circonvallazione, and in front of the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella's apse from which it takes its name. As well as numerous high speed trains to major Italian cities Florence is served by international overnight sleeper services to Munich and Vienna operated by Austrian railways ÖBB.

Train tickets must be validated before boarding. The main bus station is next to Santa Maria Novella railway station. Trenitalia runs trains between the railway stations within the city, and to other destinations around Italy and Europe. The central railway station, Santa Maria Novella, is about 500 m (1,600 ft) northwest of the Piazza del Duomo. There are two other important stations: Campo di Marte and Rifredi. Most bundled routes are Firenze–Pisa, Firenze–Viareggio and Firenze–Arezzo (along the main line to Rome). Other local railways connect Florence with Borgo San Lorenzo in the Mugello area (Faentina railway) and Siena.

A new high-speed rail station is under construction and is contracted to be operational by 2015.[123] It is planned to be connected to Vespucci airport, Santa Maria Novella railway station, and to the city centre by the second line of Tramvia.[124] The architectural firms Foster + Partners and Lancietti Passaleva Giordo and Associates designed this new rail station.[125]

Education

The University of Florence was first founded in 1321, and was recognized by Pope Clement VI in 1349. In 2019, over 50,000 students were enrolled at the university. The European University Institute has been based in the suburb of Fiesole since 1976. Several American universities host a campus in Florence, including New York University, Marist College, Pepperdine, Stanford, Florida State, Kent State, and James Madison. The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies is based in Villa I Tatti. The center for arts and humanities advanced research has been located on the border of Florence, Fiesole and Settignano since 1961. Over 8,000 American students are enrolled for study in Florence, although mostly while studying in US based degree programs.[126]

The private school, Centro Machiavelli [d] which teaches Italian language and culture to foreigners, is located in Piazza Santo Spirito in Florence.

Notable residents

- Antonia of Florence, saint

- Agnes of Montepulciano, saint

- Harold Acton, author and aesthete

- John Argyropoulos, scholar

- Leone Battista Alberti, polymath

- Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), poet

- Giovanni Boccaccio, poet

- Cesare Bomboni, architect

- Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510), painter

- Egisto Bracci (1830–1909), architect

- Aureliano Brandolini, agronomist and development cooperation scholar

- Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 19th-century English poets

- Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446), architect

- Michelangelo Buonarroti, sculptor, painter, author of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and David

- Francesco Casagrande (born 1970), cyclist

- Roberto Cavalli (1940–2024), fashion designer

- Carlo Collodi (1826–1890), writer

- Enrico Coveri, fashion designer

- Donatello (1386–1466), sculptor

- Oriana Fallaci (1929–2006), journalist and author

- Salvatore Ferragamo, fashion designer and shoemaker

- Mike Francis (born Francesco Puccioni, 1961–2009), singer and composer

- Silpa Bhirasri (born Corrado Feroci, 1892–1962), sculptor, credited as the principal figure of modern art in Thailand[127]

- Frescobaldi family, notable bankers and wine producers

- Galileo Galilei, Italian physicist, astronomer, and philosopher

- Giotto (1267–1337), early 14th-century painter, sculptor and architect

- Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455), sculptor

- Guccio Gucci (1881–1953), founder of the Gucci label

- Pauline von Hügel (1858–1901), baroness, writer, philanthropist

- Bruno Innocenti (1906–1986), sculptor

- Robert Lowell, poet

- Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527), poet, philosopher and political thinker, author of The Prince and The Discourses

- Masaccio, painter

- Rose McGowan, Florence-born actress

- Medici family

- Girolamo Mei (1519–1594), historian and humanist

- Antonio Meucci (1808–1889), inventor of the telephone

- Pirrho Musefili, Florentine cryptographer and cryptanalyst

- Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), pioneer of modern nursing, and statistician

- Virginia Oldoini (1837–1899), Countess of Castiglione, early photographic artist, secret agent and courtesan

- Valerio Profondavalle, Flemish painter

- Giulio Racah (1909–1965), Italian-Israeli mathematician and physicist; Acting President of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Raphael, painter

- Anna Sarfatti (born 1950), children's author

- Girolamo Savonarola, reformist

- Adriana Seroni (1922–1984), politician

- Giovanni Spadolini (1925–1994), politician

- Antonio Squarcialupi (1416–1480), organist and composer

- Andrei Tarkovsky, film director. Lived in the city during his exile[128]

- Evangelista Torricelli, Italian physicist

- Anna Tonelli (c. 1763–1846), Florence born portrait painter in the late 17th century and early 18th century[129]

- Maria Giustina Turcotti (c. 1700 – after 1763), opera singer[130]

- Giorgio Vasari, painter, architect, and historian

- Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512), explorer and cartographer, namesake of the Americas

- Coriolano Vighi, (1846–1905), landscape painter

- Leonardo da Vinci, polymath

- Lisa del Giocondo (1479–1542), model of the Mona Lisa

- Giorgio Antonucci, physician, psychoanalyst and an international reference on the questioning of the basis of psychiatry

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Florence is twinned with:[131]

- Bethlehem, Palestine

- Budapest, Hungary

- Dresden, Germany

- Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom

- Fez, Morocco

- Isfahan, Iran

- Kassel, Germany

- Kyiv, Ukraine

- Kuwait City, Kuwait

- Kyoto, Japan

- Nanjing, China

- Nazareth, Israel

- Philadelphia, United States

- Puebla, Mexico

- Reims, France

- Riga, Latvia

- Salvador, Brazil

- Sydney, Australia

- Tirana, Albania

- Turku, Finland

- Valladolid, Spain

Other partnerships

Florence has friendly relations with:[131]

- Arequipa, Peru

- Cannes, France

- Gifu, Japan

- Jeonju, South Korea

- Kraków, Poland

- Malmö Municipality, Sweden

- Ningbo, China

- Porto-Vecchio, France

- Providence, Rhode Island, United States

- Tallinn, Estonia

See also

- Chancellor of Florence

- Cronaca fiorentina

- European University Institute

- List of historic states of Italy

- List of squares in Florence

- Category:Buildings and structures in Florence

Notes

- ^ Obsolete Tuscan form: Fiorenza [fjoˈrɛntsa], from Latin: Florentia.

References

- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Bilancio demografico anno 2015 e popolazione residente al 31 dicembre; Comune: Firenze". ISTAT. Select: Italia Centrale/Toscana/Firenze/Firenze.

- ^ Paoletti, John T. and Radke, Gary M., Art in Renaissance Italy, Laurence King Publishing, 2005, p.79ISBN 1-85669-439-9

- ^ "Bilancio demografico mensile". demo.istat.it. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "Economy of Renaissance Florence, Richard A. Goldthwaite, Book – Barnes & Noble". Search.barnesandnoble.com. 23 April 2009. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ^ "Firenze-del-rinascimento: Documenti, foto e citazioni nell'Enciclopedia Treccani".

- ^ Spencer Baynes, L.L.D., and W. Robertson Smith, L.L.D., Encyclopædia Britannica. Akron, Ohio: The Werner Company, 1907: p. 675

- ^ "Florence | History, Geography, & Culture". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Brucker, Gene A. (1969). Renaissance Florence. New York: Wiley. p. 23. ISBN 0-520-04695-1.

- ^ "storia della lingua in 'Enciclopedia dell'Italiano'". Treccani.it. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Florence (Italy)". Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved 22 January 2010.

- ^ a b c "Fashion: Italy's Renaissance". Time. 4 February 1952. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Kiladze, Tim (22 January 2010). "World's Most Beautiful Cities". Forbes. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ "Paris Towers Over World of Fashion as Top Global Fashion Capital for 2015". Languagemonitor.com. 6 July 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ^ Gasca Queirazza, Giuliano; Marcato, Carla; Pellegrini, Giovan Battista; Petracco Sicardi, Giulia; Rossebastiano, Alda (2006). Dizionario di toponomastica: storia e significato dei nomi geografici italiani (in Italian). Turin: UTET. pp. 322–323. ISBN 88-02-07228-0.

- ^ "History of Italian Language: From the Origins to the Present Day". Europass. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ Alighieri, Scuole d'italiano Dante (9 October 2018). "History of the Italian language: the literary language". Scuole d'italiano per stranieri Società Dante Alighieri. Archived from the original on 19 June 2023. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ johndeike (3 March 2021). "The Architects and Origins Behind the Italian Language". Italian Sons and Daughters of America. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "History of Florence". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher (1994). Florence: The Biography of a City. Penguin Books. p. 4. ISBN 0-14-016644-0.

- ^ "Cradle of capitalism". The Economist. 16 April 2009. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ defeated by Genoa in 1284 and subjugated by Florence in 1406

- ^ Peters, Edward (1995). "The Shadowy, Violent Perimeter: Dante Enters Florentine Political Life". Dante Studies, with the Annual Report of the Dante Society (113): 69–87. JSTOR 40166507.

- ^ Day, W.R. (3 January 2012). "The population of Florence before the Black Death: survey and synthesis". Journal of Medieval History. 28 (2): 93–129. doi:10.1016/S0304-4181(02)00002-7. S2CID 161168875.

- ^ "Decameron Web, Boccaccio, Plague". Brown University.

- ^ Eimerl, Sarel (1967). The World of Giotto: c. 1267–1337. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 184. ISBN 0-900658-15-0.

- ^ Pallanti, Giuseppe (2006). Mona Lisa Revealed: The True Identity of Leonardo's Model. Florence, Italy: Skira. pp. 17, 23, 24. ISBN 88-7624-659-2.

- ^ "Treccani - la cultura italiana | Treccani, il portale del sapere".

- ^ "History of Florence". Britannica.com. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Laurentian Library". michelangelo.net. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Davis-Marks, Isis (2 June 2021). "Italian Art Restorers Used Bacteria to Clean Michelangelo Masterpieces". Smithsonian. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Billy (19 August 2020). "The Time When Jesus Was The King Of Florence". ucatholic.com. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "July 3, 1944 newspaper archive". Canberra Times. 3 July 1944.

- ^ "Agosto 1944: la battaglia di Firenze « Storia di Firenze". www.storiadifirenze.org. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "University Study Center, Florence « The GI University Project". Giuniversity.wordpress.com. 4 July 2010. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ Turner, Joseph Mallord William (1819). "Fiesole from the River Mugnone outside of Florence". Tate. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Dinelli, Enrico (January 2005). "Sources of major and trace elements in the stream sediments of the Arno river catchment (northern Tuscany, Italy)". Geochemical Journal. 39 (6): 531–545. Bibcode:2005GeocJ..39..531D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.605.4368. doi:10.2343/geochemj.39.531. S2CID 129636310. Retrieved 15 February 2020 – via ResearchGate.

Map showing the Arno river catchment and its major tributaries, the largest towns, and the sampling stations subdivided according to the sampling year. Coordinates refer to UTM32T (ED50) system.

- ^ "World map of Köppen – Geiger Climate Classification". koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at. April 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Borchi, Emilio; Macii, Renzo (2011). La neve a Firenze (1874–2010) [Snow in Florence (1874–2010)] (in Italian). Florence: Pagnini. ISBN 978-88-8251-382-5.

- ^ MeteoAM.it! Il portale Italiano della Meteorologia (20 May 2005). "MeteoAM.it! Il portale Italiano della Meteorologia". Meteoam.it. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 22 January 2010.