| Potonchán | |

|---|---|

| City-state of Maya | |

| 1519 | |

Monument to the Mayan chief Tabscoob in Villahermosa, Tabasco. | |

Location of Potonchan in modern Mexico. | |

| Demonym | Maya |

| Government | |

| Cacique | |

• 1518-1519 | Tabscoob |

| Today part of | Mexico |

...There exists a great city extending along the Tabasco river; so great and celebrated, as one cannot measure, however, says the pilot Alaminos and others with him, that is extends flanking the coast, about five hundred thousand steps and has twenty-five thousand houses, dispersed among gardens, that are made splendidly with stones and lime in whose construction projects the admirable industry and are of the architects...

— Peter Martyr, De Insulis, p. 349

Potonchán, was a Chontal Maya city, capital of the minor kingdom known as Tavasco or Tabasco. It occupied the left bank of the Tabasco River, which the Spanish renamed the Grijalva River, in the current Mexican state of Tabasco.

Juan de Grijalva arrived to this town on June 8, 1518, and christened the river with his name and met with the Maya chief Tabscoob to whom, it is said, he gave his green velvet doublet.

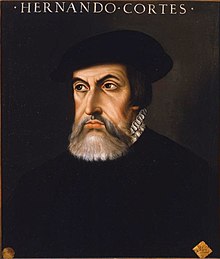

Later, on March 12, 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived. Cortés, unlike Grijalva, was received by the natives in a warlike fashion, leading to the Battle of Centla. After the native defeat, Cortés founded the first Spanish settlement in New Spain, the town of Santa María de la Victoria, on top of Potonchán.

Toponymy

The word Potonchán comes from the Nahuatl: "pononi" means "smell" and "chan" is a toponymic termination; therefore, it translates as "place that smells." Another, more plausible, etymology is that "poton" comes from the name the Chontal Maya called themselves: the Putún Maya which was also spelled Poton; thus it most likely translates as "Poton place."

Location and environment

The city of Potonchán was located on the left on delivered of the Tabasco River, which was christened the Grijalva River by the Spaniards, and according to the chronicles of Bernal Diaz del Castillo, it was a league from the coast.

The city was located on a small hill of sandstone, practically surrounded by water on three sides. On one side was, the river, and on the other two sides, swamps. It was in a region of extensive floodplains.

Potonchán was the capital of the cacicazgo of Tabasco, and was one of two principal cities of the Chontal Maya, along with Itzamkanac, capital of the cacicazgo of Acalán. However, unlike Itzamkanac which was located in the midst of the jungle, Potonchán was a maritime port and fluvial, which allowed it to have an intense commercial exchange both with the towns of the Yucatán Peninsula and with those of the central High Plains.

The Chontal Maya took full advantage of their environment, using the rivers as routes of transportation and communication with different Mayan cities and provinces. They were good navigators and merchants and controlled many maritime routes around the Yucatán Peninsula, from the Laguna de Términos in Campeche to the center of Sula in Honduras.

At a point located between the current states of Tabasco and Campeche, the Mexica port of Xicalango was found with whom Potochán fought countless wars for control of the territory. The last of these great wars was won by Potonchán just before the year 1512. In tribute, the people of Xicalango presented several women to the chief Tascoob, one of which was Malintzin (famed as "La Malinche"), who was later given to Cortés after the Battle of Centla in 1519.

Description of the population

The little that is known of Potonchán is thanks to the chronicles of the Spanish conquistadors. With regards to its population, it is known that it was one of the most populated Mayan cities of the Tabasco Plain, because the cleric Juan Díaz, in his "Itinerary," speaks of the arrival of Juan de Grijalva's expedition in 1518, it "had more than two thousand Indians..."[1]

For his part, Bernal Diaz del Castillo in Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España, says that when they reached Potonchán, it had "over twelve thousand warriors ready to attack [in the main square], plus the riverbank was all full of Indians in the bushes...."[2]

Peter Martyr says in his chronicle, that "the great city flanks the river of Tabasco, so great that it has twenty-five thousand houses..." This gives us an idea of the size of the city and of the quantity of inhabitants Potonchán would have had, as well as the natives that were living in nearby towns under control of Potonchán proper.[3]

The city was very inhabited, the houses were made mostly of adobe.

Potonchán counted on intense commercial activity, in fact, this was the predominant activity. Across the sea, Potonchán had an important river-based trade with towns like Guazacualco, Xicalango, Chakán Putum and Kaan Peech. It also had commercial ties to the Mayan provinces of Acalán and Mazatlán located in the jungles of what is today the border area of the states Tabasco and Campeche with Guatemala. This trade reached as far as the port of Nito on Guatemala's Atlantic Coast.

Regarding the urban design of the city, very little is known. Owing to the nature of the place, in which many structures were made of "seto" (hedgerows) and "guano" (palms of genus Coccothrinax). In other cases, the vestiges disappeared at the initiation of Spanish construction of the town of Santa María de la Victoria, which was built over top the indigenous structures.

The Tabascan historian Manuel Gil Saenz reports that around the year 1872, near the port of Frontera, excavations resulting from some "monterías" (logging camps) discovered several remains of columns, idols, jars, vases and even ruins of pyramids.[4]

History

Founding

Although the date of its foundation is unknown, it is known that it was due to the separation that occurred among the Maya of Mayapan and the Chontal Maya. The latter formed Potonchán's kingdom, whose head was Tabscoob, who ruled under the name of chief or lord of Tabasco.[5]

The encounter between Juan de Grijalva and the Mayan chief Tabscoob occurred in Potonchán on June 8, 1518.

For its internal government, having the same Mayan costumes and laws, they adopted the same governmental system that existed from when they were united until the collapse of the Mayan empire. That is, with the three existing social classes: nobility and the priesthood, tributaries, and slaves.[4] It was like that until the arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519.

Arrival of Juan de Grijalva in 1518

The first Spanish expedition to touch Tabascan land was led by Juan de Grijalva, who on June 8, 1518, discovered for Western eyes the territory that is now the state of Tabasco. Grijalva arrived that day at the mouth of a great river, which the crew named "Grijalva" in honor of their captain, its discoverer.

Juan de Grijalva decided to go down the river to discover the inland area, and found four canoes full of Indians, painted and making gesticulations and gestures of war. They showed their displeasure with his arrival,[6] but Grijalva sent the Indians Julián and Melchorejo so that they could explain to the natives in the Mayan tongue that they came in peace. Thus they continued along the river and, after less than a league, discovered the population of Potonchán.

"We started eight days in June 1518 and going armed to the coast, about six miles away from land, we saw a very large stream of water coming out of a major river, the fresh water was spewing approximately six miles out to sea. And with that current we could not enter by said river, which we named the Grijalva River. We were being followed by more than two thousand Indians and they were making signs of war (...) This river flows from very high mountains, and this land seems to be the best upon which the sun shines; if it were to be more settled, it would serve well as a capital: it is called the Potonchán province."

— Juan Díaz, Itinerary of Grijalva (1518)

Once ashore, Juan de Grijalva, with the help of Mayan interpreters that he had taken earlier, began to strike up a friendly dialog. In addition to flattering the natives with gifts, Grijalva begged them to call their boss to meet and hold talks with him. And so, after a while, the chief Tabscoob appeared with his nobles to greet Grijalva.[6] During the talk, both figures exchanged gifts: to Grijalva, Tabscoob presented some gold plates in the form of armor and some feathers; whereas Grijalva gave the Mayan chief his green velvet doublet.

Tabscoob told the Spanish captain of a place called Culua that was "toward where the sun set..." there was much more of that material. Grijalva in turn, spoke with the Mayan chief with courtesy, admitting that he came in the name of a great lord named Charles V, who was very good, and he wanted to have them as vassals. Tabscoob responded that they lived happily as they were, and that they needed no other lord, and that if he wanted to preserve his friendship with Tabscoob, Grijalva's expedition should leave. Grijalva, after stocking water and provisions, embarked on his way to Culua (modern-day San Juan de Ulúa).[6]

Arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519

Nearly a year after, on March 12, 1519, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived at the mouth of the Grijalva river. He decided to have his ships drop anchor and enter the river in skiffs, in search of the great city of Indians described by Juan de Grijalva.

Cortés landed right at the mouth of the river, at a place named "Punta de los Palmares."

"On the twelfth day of the month of March of the year one-thousand five-hundred nineteen, we arrived at the Grijalva river, that is called Tabasco(...) and in the skiffs we all went to disembark at the Punta de los Palmares," that was by the town of Potonchán or Tabasco, about half a league. They walked along the river and on the shore among bushes all full of Indian warriors(...) and so on, they were together in the village more than two thousand warriors prepared to make war with us..."

— Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España (1519)[7]: 68

To discover their intentions, Cortés, by way of a translator, told some natives that were in a boat that "he would do no harm, to those who came in peace and that he only wanted to speak with them."[8] But Cortés, seeing that the natives were still threatening, ordered weapons brought on the boats and handed them to archers and musketeers, and he began planning how to attack the town.[8]

On the day following March 13, 1519, the chaplain Juan Díaz and Brother Bartolomé of Olmedo, officiated what was the first Christian mass in the continental territory of New Spain. Afterwards, Cortés sent Alonso de Ávila with one hundred soldiers out on the road leading to the village, while Cortés and the other group of soldiers went in the boats. There, on the shore, Cortés made a "requerimiento" (requisition) in front of a notary of the king named Diego de Godoy, to let them disembark,[8] thus issuing the first notarial act in Mexico.[9]

The natives refused, telling the Spaniards that, if they disembarked, they would be killed. They began to shoot arrows at Cortés' soldiers, initiating combat.[10]

"... and they surrounded us with their canoes with such a spray of arrows that they made us stop with water up to our waists, and there was so much mud that we could get out and many Indians charged us with spears and others pierced us with arrows, ensuring that we did not touch land as soon as we would have liked, and with so much mud we couldn't even move, and Cortés was fighting and he lost a shoe in the mud and came to land with one bare foot(...) and we were upon them on land crying to St. James and we made them retreat to a wall that was made of timber, until we breached it and came in to fight with them(...) we forced them through a road and there they turned to fight face-to-face and they fought very valiantly...."

— Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de populationla Nueva España (1519)[7]: 70

Alonso de Ávila arrived to the combat developing within Potonchán with his hundred men who went traveled by land, making the Indians flee and take refuge in the mountains.

In this manner, Cortés took possession of the great main square of Potonchán, in which there were rooms and great halls and which had three houses of idols.[11]

"...we came upon a great courtyard, which had some chambers and great halls, and had three houses of idols. In the "cúes" [temples] of that court, which Cortés ordered that we would repair (...) and there Cortés took possession of the land, for his Majesty and in his royal name, in the following manner: His sword drawn, he dealt three stabs to a large ceiba tree in a sign of possession. The tree was in the square of that great town and he said that if there were one person that contradicted him, he would defend it with his sword and all those that were present said it was okay to take the land (...) And before a notary of the king that decree was made... "

— Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España (1519)[7]: 71

Battle of Centla

The next day, Captain Cortés sent Pedro de Alvarado with a hundred soldiers so that he could go up to six miles inland, and he sent Francisco de Lugo, with another hundred soldiers, to a different part. Francisco de Lugo ran into warrior squads, starting a new battle. Upon hearing the shots and drums, Alvarado went in aid of Lugo, and together, after a long fight, they were able to make the natives flee. The Spaniards returned to town to inform Cortés.[12]

Hernán Cortés was informed by an Indian prisoner that the Indians would attack the town, and so he ordered that all the horses be unloaded from the ships and that soldiers prepare their weapons.

The next day, early in the morning, Cortés and his men went through plains to Cintla or Centla, subject towns of Potonchán, where the day before Alvarado and Lugo had fought against the natives. There they found thousands of Indians, beginning Battle of Centla.

The Spaniards were attacked by Chontal Maya Indians. The Spaniards defended themselves with firearms like muskets and cannons, which produced terror in the Indians, but what terrified them more was seeing the Spanish cavalry, which they had never seen. The Indians believed that both rider and horse were one. In the end the Indians lost, owing primarily to the higher technology of the Spaniard's weapons.

"... And we came upon them with all the Captaincies and squads. They had departed in search of us, and they brought great plumes, drums and small trumpets. Their faces were red with ochre, pale and dark. They had great bows and arrows and spears and bucklers (...) and they were in such large squads that all the savanna was covered. They came furiously and surrounded us on all sides. The first attack wounded more than seventy of us, and there were three hundred Indians for each one of us (...) and being in this, we saw how the cavalry came from behind them and we trapped them with them on one side and we on the other. And the Indians believed that the horse and the rider were one, as they had never seen horses before..."

— Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España (1519)[7]: 75–76

After the battle ended, Cortés and his men returned to Potonchán, and where they healed the wounded and buried the dead. On the following day, ambassadors sent by Tabscoob arrived at the Spanish camp with gifts because, according to Indian tradition, the loser must give gifts to the winner. Among the gifts were gold, jewelry, jade, turquoise, animal skins, domestic animals, feathers of precious birds, etc.

Furthermore, the Indians gave the Europeans 20 young women, including a woman who has been referred to as Malintze,[13] Malintzin, and Malinalli by differing sources. The Spaniards gave her the name Dona Marina, and she served as counselor and interpreter for Cortés. Later, Cortés had a son with her.[7]: 80–82

References

- ^ Cabrera Bernat 1987, p. 25.

- ^ Cabrera Bernat 1987, p. 41.

- ^ Gil y Sáenz 1979, p. 87.

- ^ a b Gil y Sáenz 1979, p. 76.

- ^ Gil y Sáenz 1979, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Gil y Sáenz 1979, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d e Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0140441239

- ^ a b c Cabrera Bernat 1987, p. 42.

- ^ Colegio de Notiarios Públicos de Tabasco. El Notariado en México

- ^ Cabrera Bernat 1987, p. 43.

- ^ Cabrera Bernat 1987, p. 44.

- ^ Cabrera Bernat 1987, p. 45.

- ^ Townsend, Camilla. Malintzin's Choices. University of New Mexico Press, 2006, p. 55.

Bibliography

- Cabrera Bernat, Cipriano Aurelio (1987), Viajeros en Tabasco: Textos, Biblioteca básica tabasqueña (in Spanish), vol. 15 (1st ed.), Villahermosa, Tabasco: Gobierno del Estado de Tabasco, Instituto de Cultura de Tabasco, ISBN 968-889-107-X

- Gil y Sáenz, Manuel (1979), Compendio Histórico, Geográfico y Estadístico del Estado de Tabasco, Serie Historia (México) (in Spanish), vol. 7 (2nd ed.), México: Consejo Editorial del Gobierno del Estado de Tabasco, OCLC 7281861

- Torruco Saravia, Geney (1987), Villahermosa Nuestra Ciudad (in Spanish) (1st ed.), Villahermosa, Tabasco: H. Ayuntamiento Constitucional del Municipio de Centro, OCLC 253403147