Yoga as therapy is the use of yoga as exercise, consisting mainly of postures called asanas, as a gentle form of exercise and relaxation applied specifically with the intention of improving health. This form of yoga is widely practised in classes, and may involve meditation, imagery, breath work (pranayama) and calming music as well as postural yoga.[1]

At least three types of health claims have been made for yoga: magical claims for medieval haṭha yoga, including the power of healing; unsupported claims of benefits to organ systems from the practice of asanas; and more or less well supported claims of specific medical and psychological benefits from studies of differing sizes using a wide variety of methodologies.

Systematic reviews have found beneficial effects of yoga on low back pain[2] and depression,[3] but despite much investigation, little or no evidence of benefit for specific medical conditions.[3][4] The study of trauma-sensitive yoga has been hampered by weak methodology.[5]

Context

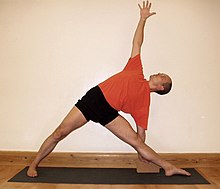

Yoga classes used as therapy usually consist of asanas (postures used for stretching), pranayama (breathing exercises), and relaxation in savasana (lying down).[7] The physical asanas of modern yoga are related to medieval haṭha yoga tradition, but they were not widely practiced in India before the early 20th century.[8]

The number of schools and styles of yoga in the Western world has grown rapidly from the late 20th century. By 2012, there were at least 19 widespread styles from Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga to Viniyoga. These emphasise different aspects including aerobic exercise, precision in the asanas, and spirituality in the haṭha yoga tradition.[6][9] These aspects can be illustrated by schools with distinctive styles. Bikram Yoga has an aerobic exercise style with rooms heated to 105 °F (41 °C) and a fixed sequence of 2 breathing exercises and 26 asanas performed in every session. Iyengar Yoga emphasises correct alignment in the postures, working slowly, if necessary with props, and ending with relaxation. Sivananda Yoga focuses more on spiritual practice, with 12 basic poses, chanting in Sanskrit, pranayama breathing exercises, meditation, and relaxation in each class, and importance is placed on a vegetarian diet.[6][9]

Types of claims

At least three different types of claims of therapeutic benefit have been made for yoga from medieval times onwards, not counting the more general claims of good health made throughout this period: magical powers, biomedical claims for marketing purposes, and specific medical claims. Neither of the first two are supported by reliable evidence. The medical claims are supported by evidence of varying quality, from case studies to controlled trials and ultimately systematic review of multiple trials.[10][11]

Magical powers

Medieval authors asserted that Haṭha yoga brought physical (as well as spiritual) benefits, and provided magical powers, including of healing. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (HYP) states that asanas in general, described as the first auxiliary of haṭha yoga, give "steadiness, good health, and lightness of limb." (HYP 1.17)[10] Specific asanas, it claims, bring additional benefits; for example, Matsyendrasana awakens Kundalini and helps to prevent semen from being shed involuntarily; (HYP 1.27) Paschimottanasana "stokes up the digestive fire, slims the belly and gives good health"; (HYP 1.29) Shavasana "takes away fatigue and relaxes the mind"; (HYP 1.32) while Padmasana "destroys all diseases" (HYP 1.47).[12] These claims lie within a tradition across all forms of yoga that practitioners can gain supernatural powers.[13] Hemachandra's Yogashastra (1.8–9) lists the magical powers, which include healing and the destruction of poisons.[14]

Biomedical claims for marketing purposes

Twentieth century advocates of some schools of yoga, such as B. K. S. Iyengar, have for various reasons made claims for the effects of yoga on specific organs, without citing any evidence. The yoga scholar Suzanne Newcombe argues that this was one of several visions of yoga as in some sense therapeutic, ranging from medical to a more popular offer of health and well-being.[15] The yoga scholar Andrea Jain describes these claims of Iyengar's in terms of "elaborating and fortifying his yoga brand"[16] and "mass-marketing",[16] calling Iyengar's 1966 book Light on Yoga "arguably the most significant event in the process of elaborating the brand."[16] The yoga teacher Bernie Gourley notes that the book neither describes contraindications systematically, nor provides evidence for the claimed benefits.[17] Jain suggests that "Its biomedical dialect was attractive to many."[16] For example, in the book, Iyengar claims that the asanas of the Eka Pada Sirsasana cycle[18]

...tone up the muscular, nervous and circulatory systems of the entire body. The spine receives a rich supply of blood, which increases the nervous energy in the chakras (the various nerve plexuses situated in the spine), the flywheels in the human body machine. These poses develop the chest and make the breathing fuller and the body firmer; they stop nervous trembling of the body and prevent the diseases which cause it; they also help to eliminate toxins by supplying pure blood to every part of the body and bringing the congested blood back to the heart and lungs for purification.[18]

The history of such claims was reviewed by William J. Broad in his 2012 book The Science of Yoga. Broad argues that while the health claims for yoga began as Hindu nationalist posturing, it turns out that there is ironically[11] "a wealth of real benefits".[11]

Types of activity

Remedial yoga

The International Association of Yoga Therapists offers a definition of yoga therapy that can encompass a wide range of activities and practices, calling it "the process of empowering individuals to progress toward improved health and well-being through the application of the teachings and practices of Yoga".[19]

The history of remedial yoga goes back to the pioneers of modern yoga, Krishnamacharya and Iyengar. Iyengar was sickly as a child, and yoga with his brother-in-law Krishnamacharya improved his health; it had also helped his daughter Geeta, so his response to his students' health issues, in Newcombe's view, "was an intense and personal one."[20] In effect Iyengar was treating "remedial yoga" as analogous to Henrik Ling's medical gymnastics.[20] As early as 1940, Iyengar was using yoga as a therapy for common conditions such as sinus problems, backache, and fatigue.[21] Iyengar was willing to push people through pain "to [show] them new possibilities."[22] In the 1960s, he trained a few people such as Diana Clifton and Silva Mehta to deliver this remedial yoga; particular asanas were used for different conditions, and non-remedial Iyengar Yoga teachers were taught to inform students that ordinary classes were not suitable for "serious health issues".[23] Mehta taught a remedial yoga class in the Iyengar Yoga Institute in Maida Vale from its opening in 1984.[24] She contributed "Remedial Programs" for conditions such as arthritis, backache, knee cartilage problems, pregnancy, sciatica, scoliosis and varicose veins in the Mehtas' 1990 book Yoga the Iyengar Way.[25] However, Iyengar was deferential to Western medicine and its assessments, so in Newcombe's view Iyengar Yoga is "positioned as complementary to standard medical treatment rather than as an alternative".[26]

Newcombe argues that in Britain, yoga "largely avoided overt conflict with the medical profession by simultaneously professionalising with educational qualifications and deferring to medical expertise."[27] After Richard Hittleman's Yoga for Health series on ITV from 1971 to 1974,[28] the series producer Howard Kent founded a charity, the Yoga for Health Foundation, for "Research into the therapeutic benefits to be obtained by the practice of yoga";[29] residential courses began in 1978 at Ickwell Bury in Bedfordshire.[30] The Foundation stated that yoga was not a therapy or cure but had "therapeutic benefits", whether physical, mental, or emotional, and it worked especially with "the physically handicapped".[31] Newcombe notes that a third organisation, the Yoga Biomedical Trust, was founded in Cambridge in 1983 by a biologist, Robin Monro, to research complementary therapies. He found it difficult to obtain research funding, and in the 1990s moved to London, focusing on training yoga teachers in yoga as therapy and providing yoga as individualised therapy, using pranayama, relaxation and asanas.[32]

Sports medicine

From the point of view of sports medicine, asanas function as active stretches, helping to protect muscles from injury; these need to be performed equally on both sides, the stronger side first if used for physical rehabilitation.[33]

Research

Methodology

Much of the research on the therapeutic use of yoga has been in the form of preliminary studies or clinical trials of low methodological quality, including small sample sizes, inadequate control and blinding, lack of randomization, and high risk of bias.[34][4] Further research is needed to quantify the benefits and to clarify the mechanisms involved.[35]

For example, a 2010 literature review on the use of yoga for depression stated, "although the results from these trials are encouraging, they should be viewed as very preliminary because the trials, as a group, suffered from substantial methodological limitations."[4] A 2015 systematic review on the effect of yoga on mood and the brain recommended that future clinical trials should apply more methodological rigour.[3]

Mechanisms

The practice of asanas has been claimed to improve flexibility, strength, and balance; to alleviate stress and anxiety, and to reduce the symptoms of lower back pain, without necessarily demonstrating the precise mechanisms involved.[37] A review of five studies noted that three psychological mechanisms (positive affect, mindfulness, self-compassion) and four biological mechanisms (posterior hypothalamus, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and cortisol) that might act on stress had been examined empirically, whereas many other potential mechanisms remain to be studied; four of the mechanisms (positive affect, self-compassion, inhibition of the posterior hypothalamus and salivary cortisol) were found to mediate yoga's effect on stress.[36]

Low back pain

Back pain is one reason people take up yoga, and since at least the 1960s some practitioners have claimed that it relieved their symptoms.[38]

A 2013 systematic review on the use of yoga for low back pain found strong evidence for short- and long-term effects on pain, and moderate evidence for long-term benefit in back-specific disability, with no serious adverse events. Ten randomised controlled trials were analysed, of which eight had a low risk of bias. The outcomes measured included improvements in "pain, back-specific disability, generic disability, health-related quality of life, and global improvement".[2] The review stated that yoga can be recommended as an additional therapy to chronic low back pain patients.[2] A 2022 Cochrane systematic review of yoga for chronic non-specific low back pain included 21 randomised controlled trials and found that yoga produced clinically unimportant improvements in pain and back-specific function. Improvements in back-specific function were similar to those obtained from other forms of therapeutic exercise, such as physical therapy.[39]

Mental disorders

Trauma-sensitive yoga has been developed by David Emerson and others of the Trauma Center at the Justice Resource Institute in Brookline, Massachusetts. The center uses yoga alongside other treatments to support recovery from traumatic episodes and to enable healing from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Workers including Bessel van der Kolk and Richard Miller have studied how clients can "regain comfort in their bodies, counteract rumination, and improve self-regulation through yoga."[40][41]

Systematic reviews indicate that yoga offers moderate benefit in the treatment of PTSD.[42][43][44] A 2017 systematic review of PTSD in post-9/11 veterans showed that participants in studies who had received mindfulness training, mind-body therapy, and yoga "reported significant improvements in PTSD symptoms".[45] Another systematic review on veterans the same year also found improvement in PTSD symptoms.[46] Other systematic reviews postulate that designing the style and instructions to the needs of the veterans leads to better results and a larger impact on PTSD symptoms.[47]

A 2013 systematic review on the use of yoga for depression found moderate evidence of short-term benefit over "usual care" and limited evidence compared to relaxation and aerobic exercise. Only 3 of 12 randomised controlled trials had a low risk of bias. The diversity of the studies precluded analysis of long-term effects.[48] A 2015 systematic review on the effect of yoga on mood and the brain concluded that "yoga is associated with better regulation of the sympathetic nervous system and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system, as well as a decrease in depressive and anxious symptoms in a range of populations."[3] A systematic review in 2017 found some evidence of benefit in major depressive disorders, examining outcomes primarily of improvements in remission rates and severity of depression (and secondarily of anxiety and adverse events), but considered that better randomised controlled trials were required.[49]

Cardiovascular health

A 2012 survey of yoga in Australia notes that there is "good evidence"[50] that yoga and its associated healthy lifestyle—often vegetarian, usually non-smoking, preferring organic food, drinking less or no alcohol–are beneficial for cardiovascular health, but that there was "little apparent uptake of yoga to address [existing] cardiovascular conditions and risk factors".[35] Yoga was cited by respondents as a cause of these lifestyle changes. The survey notes that the relative importance of the various factors had not been assessed.[35]

Other conditions

There is little reliable evidence that yoga is beneficial for specific medical conditions, and an increasing amount of evidence that it is not.

| Condition | Study | Date | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| rheumatic diseases | Systematic review | 2013 | Weak support in terms of pain and disability, no evidence on safety[51] |

| epilepsy or menopause-related symptoms | Systematic review | 2015 | No evidence of benefit[52][53] |

| Cancer | American Cancer Society's opinion | 2019 | Can improve strength and balance; is "unlikely to cause harm", does not "interfere with cancer treatment";[54] "cannot cure cancer";[55] may improve quality of life in cancer survivors, as in a randomised controlled trial of women who had had breast cancer. Measured outcomes included fatigue, depression, and sleep quality.[55][56] |

| Dementia | Systematic review | 2015 | "Promising" evidence that exercise helps with activities of daily living; no evidence of benefit to cognition, neuropsychiatric symptoms, or depression; yoga was not distinguished from other forms of exercise.[57] |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Systematic review | 2010 | No effect, measured by teacher rating on the ADHD overall scale.[34] |

| Female urinary incompetence | Systematic review | 2019 | Insufficient evidence[58] |

Safety

Although relatively safe, yoga is not a risk-free form of exercise. Sensible precautions can usefully be taken, such as avoiding advanced moves by beginners, not combining practice with psychoactive drug use, and avoiding competitiveness.[59]

A small percentage of yoga practitioners each year suffer physical injuries analogous to sports injuries.[60] The practice of yoga has been cited as a cause of hyperextension or rotation of the neck, which may be a precipitating factor in cervical artery dissection.[61]

See also

References

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg (2006). "Yogic Meditation". In Jonathan Shear (ed.). The Experience of Meditation. St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House. p. 90.

While not every branch or school of yoga includes meditation in its technical repertoire, most do.

- ^ a b c Cramer, Holger; Lauche, Romy; Haller, Heidemarie; Dobos, Gustav (2013). "A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Yoga for Low Back Pain". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 29 (5): 450–460. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. PMID 23246998. S2CID 12547406.

- ^ a b c d Pascoe, Michaela C.; Bauer, Isabelle E. (1 September 2015). "A systematic review of randomised control trials on the effects of yoga on stress measures and mood". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 68: 270–282. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.07.013. PMID 26228429.

- ^ a b c Uebelacker, L. A.; Epstein-Lubow, G.; Gaudiano, B. A.; Tremont, G.; Battle, C. L.; Miller, I. W. (2010). "Hatha yoga for depression: critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 16 (1): 22–33. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. PMID 20098228. S2CID 205423922.

- ^ Nguyen-Feng, Viann N.; Clark, Cari J.; Butler, Mary E. (August 2019). "Yoga as an intervention for psychological symptoms following trauma: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis". Psychological Services. 16 (3): 513–523. doi:10.1037/ser0000191. PMID 29620390. S2CID 4607801.

- ^ a b c Anon (13 November 2012). "What's Your Style? Explore the Types of Yoga". Yoga Journal.

- ^ Forbes, Bo. "Yoga Therapy in Practice: Using Integrative Yoga Therapeutics in the Treatment of Comorbid Anxiety and Depression". International Journal of Yoga. 2008: 87.

- ^ Singleton 2010, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Beirne, Geraldine (10 January 2014). "Yoga: a beginner's guide to the different styles". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ a b Mallinson & Singleton 2017, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Broad 2012, pp. 39 and whole book.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 108–111.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 359–361.

- ^ Mallinson & Singleton 2017, pp. 385–387.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, pp. 203–227, Chapter "Yoga as Therapy".

- ^ a b c d Jain 2015, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Gourley, Bernie (1 June 2014). "Book Review: Light on Yoga by BKS Iyengar". The !n(tro)verted yogi. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ a b Iyengar 1979, p. 302, and whole book.

- ^ "Contemporary Definitions of Yoga Therapy". International Association of Yoga Therapists. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ^ a b Newcombe 2019, p. 215.

- ^ Goldberg 2016.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 216.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 217.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 221.

- ^ Mehta, Mehta & Mehta 1990, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 219.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 206.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 189.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 209.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 211.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, pp. 212–214.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, pp. 222–225.

- ^ Srinivasan, T. M. (2016). "Dynamic and static asana practices". International Journal of Yoga. 9 (1). Medknow: 1–3. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.171724. PMC 4728952. PMID 26865764.

- ^ a b Krisanaprakornkit, T.; Ngamjarus, C.; Witoonchart, C.; Piyavhatkul, N. (2010). "Meditation therapies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 (6): CD006507. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006507.pub2. PMC 6823216. PMID 20556767.

- ^ a b c Penman, Stephen; Stevens, Philip; Cohen, Marc; Jackson, Sue (2012). "Yoga in Australia: Results of a national survey". International Journal of Yoga. 5 (2): 92–101. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.98217. ISSN 0973-6131. PMC 3410203. PMID 22869991.

- ^ a b Riley, Kristen E.; Park, Crystal L. (2015). "How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry". Health Psychology Review. 9 (3): 379–396. doi:10.1080/17437199.2014.981778. PMID 25559560. S2CID 35963343.

- ^ Hayes, M.; Chase, S. (March 2010). "Prescribing Yoga". Primary Care. 37 (1): 31–47. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.009. PMID 20188996.

- ^ Newcombe 2019, p. 203.

- ^ Wieland, L Susan; Skoetz, Nicole; Pilkington, Karen; Harbin, Shireen; Vempati, Ramaprabhu; Berman, Brian M (18 November 2022). "Yoga for chronic non-specific low back pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (11): CD010671. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010671.pub3. PMC 9673466. PMID 36398843.

- ^ Jackson, Kate. "Trauma-Sensitive Yoga". Social Work Today.

- ^ Nolan, Caitlin R. (2016). "Bending without breaking: A narrative review of trauma-sensitive yoga for women with PTSD". Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 24: 32–40. doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.05.006. PMID 27502798.

- ^ Uebelacker, Lisa (20 March 2016). "Yoga for Depression and Anxiety: A Review of Published Research and Implications for Healthcare Providers" (PDF). Rhode Island Medical Journal. 99 (3): 20–22. PMID 26929966.

- ^ Nguyen-Feng, Viann N.; Clark, Cari J.; Butler, Mary E. (August 2019). "Yoga as an intervention for psychological symptoms following trauma: A systematic review and quantitative synthesis". Psychological Services. 16 (3): 513–523. doi:10.1037/ser0000191. PMID 29620390. S2CID 4607801.

- ^ Cramer, Holger; Anheyer, Dennis; Saha, Felix J.; Dobos, Gustav (March 2018). "Yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder – a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 18 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/s12888-018-1650-x. PMC 5863799. PMID 29566652.

- ^ Cushing, R. E.; Braun, K. L. (2018). "Mind-Body Therapy for Military Veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 24 (2): 106–114. doi:10.1089/acm.2017.0176. PMID 28880607.

- ^ Niles, Barbara (21 March 2018). "A systematic review of randomized trials of mind-body interventions for PTSD" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Psychology. 74 (9): 1485–150. doi:10.1002/jclp.22634. PMC 6508087. PMID 29745422.

- ^ Robin, Cushing (30 April 2018). "Military-Tailored Yoga for Veterans with Post-traumatic Stress Disorder". Military Medicine. 183 (5–6): e223–e231. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx071. PMC 6086130. PMID 29415222.

- ^ Cramer, Holger; Lauche, Romy; Langhorst, Jost; Dobos, Gustav (2013). "Yoga for Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Depression and Anxiety. 30 (11): 1068–1083. doi:10.1002/da.22166. PMID 23922209. S2CID 8892132.

- ^ Cramer, Holger; Anheyer, Dennis; Lauche, Romy; Dobos, Gustav (2017). "A systematic review of yoga for major depressive disorder". Journal of Affective Disorders. 213: 70–77. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.006. hdl:10453/79255. PMID 28192737.

- ^ For example, the survey by Penman and Stevens cites: Jayasinghe, S. R. (2004). "Yoga in cardiac health (A Review)". European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 11 (5): 369–375. doi:10.1097/01.hjr.0000206329.26038.cc. ISSN 1741-8267. PMID 15616408. S2CID 27316719.

- ^ Cramer, H.; Lauche, R.; Langhorst, J.; Dobos, G. (November 2013). "Yoga for rheumatic diseases: a systematic review". Rheumatology (Oxford). 52 (11): 2025–30. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ket264. PMID 23934220.

- ^ Panebianco, Mariangela; Sridharan, Kalpana; Ramaratnam, Sridharan (2 May 2015). Panebianco, Mariangela (ed.). "Yoga for epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD001524. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001524.pub2. PMID 25934967.

- ^ Lee, M. S.; Kim, J. I.; Ha, J. Y.; Boddy, K.; Ernst, E. (2009). "Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review". Menopause. 16 (3): 602–608. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31818ffe39. PMID 19169169. S2CID 205611941.

- ^ "The Truth About Alternative Medical Treatments". American Cancer Society. 30 January 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Say Yes to Yoga". American Cancer Society. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Chandwani, Kavita D.; Perkins, George; Nagendra (2014). "Randomized, Controlled Trial of Yoga in Women With Breast Cancer Undergoing Radiotherapy". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 32 (10): 1058–1065. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2752. ISSN 0732-183X. PMC 3965260. PMID 24590636.

- ^ Forbes, Dorothy; Forbes, Scott C.; Blake, Catherine M.; Thiessen, Emily J.; Forbes, Sean (15 April 2015). "Exercise programs for people with dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (4): CD006489. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub4. PMC 9426996. PMID 25874613.

- ^ Wieland, L. Susan; Shrestha, Nipun; Lassi, Zohra S.; Panda, Sougata; Chiaramonte, Delia; Skoetz, Nicole (2019). "Yoga for treating urinary incontinence in women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (2): CD012668. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012668.pub2. PMC 6394377. PMID 30816997.

- ^ Cramer, H.; Krucoff, C.; Dobos, G. (2013). "Adverse events associated with yoga: a systematic review of published case reports and case series". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e75515. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875515C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075515. PMC 3797727. PMID 24146758.

- ^ Penman, S.; Cohen, M.; Stevens, P.; Jackson, S. (July 2012). "Yoga in Australia: Results of a national survey". International Journal of Yoga. 5 (2): 92–101. doi:10.4103/0973-6131.98217. PMC 3410203. PMID 22869991.

- ^ Caso, V.; Paciaroni, M.; Bogousslavsky, J. (2005). "Environmental factors and cervical artery dissection". Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. 20: 44–53. doi:10.1159/000088134. ISBN 3-8055-7986-1. PMID 17290110.

Sources

- Broad, William J. (2012). The Science of Yoga: The Risks and the Rewards. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4142-4.

- Goldberg, Elliott (2016). The Path of Modern Yoga : the history of an embodied spiritual practice. Inner Traditions. ISBN 978-1-62055-567-5. OCLC 926062252.

- Iyengar, B. K. S. (1979) [1966]. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Unwin Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1855381667.

- Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga : from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- Mallinson, James; Singleton, Mark (2017). Roots of Yoga. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-241-25304-5. OCLC 928480104.

- Mehta, Silva; Mehta, Mira; Mehta, Shyam (1990). Yoga the Iyengar Way: The new definitive guide to the most practised form of yoga. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0863184208.

- Newcombe, Suzanne (2019). Yoga in Britain: Stretching Spirituality and Educating Yogis. Bristol, England: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78179-661-0.

- Singleton, Mark (2010). Yoga Body : the origins of modern posture practice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539534-1. OCLC 318191988.

External links

- International Association of Yoga Therapists

- Vox: I read more than 50 scientific studies about yoga. Here's what I learned by Julia Belluz