The works of Rabindranath Tagore consist of poems, novels, short stories, dramas, paintings, drawings, and music that Bengali poet and Brahmo philosopher Rabindranath Tagore created over his lifetime.

Tagore's literary reputation is disproportionately influenced by regard for his poetry; however, he also wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas, and thousands of songs. Of Tagore's prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; indeed, he is credited with originating the Bengali-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic, and lyrical nature. However, such stories mostly borrow from deceptively simple subject matter — the lives of ordinary people and children.

Drama

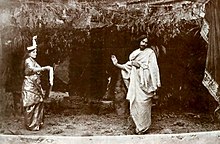

At sixteen, Tagore led his brother Jyotirindranath's adaptation of Molière's Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme.[1] At twenty he wrote his first drama-opera: Valmiki Pratibha (The Genius of Valmiki). In it the pandit Valmiki overcomes his sins, is blessed by Saraswati, and compiles the Rāmāyana.[2] Through it Tagore explores a wide range of dramatic styles and emotions, including usage of revamped kirtans and adaptation of traditional English and Irish folk melodies as drinking songs.[3] Another play, written in 1912, Dak Ghar (The Post Office), describes the child Amal defying his stuffy and puerile confines by ultimately "fall[ing] asleep", hinting his physical death. A story with borderless appeal—gleaning rave reviews in Europe—Dak Ghar dealt with death as, in Tagore's words, "spiritual freedom" from "the world of hoarded wealth and certified creeds".[4][5] In the Nazi-besieged Warsaw Ghetto, Polish doctor-educator Janusz Korczak had orphans in his care stage The Post Office in July 1942.[6] In The King of Children, biographer Betty Jean Lifton suspected that Korczak, agonising over whether one should determine when and how to die, was easing the children into accepting death.[7][8][9] In mid-October, the Nazis sent them to Treblinka.[10]

[I]n days long gone by [...] I can see [...] the King's postman coming down the hillside alone, a lantern in his left hand and on his back a bag of letters climbing down for ever so long, for days and nights, and where at the foot of the mountain the waterfall becomes a stream he takes to the footpath on the bank and walks on through the rye; then comes the sugarcane field and he disappears into the narrow lane cutting through the tall stems of sugarcanes; then he reaches the open meadow where the cricket chirps and where there is not a single man to be seen, only the snipe wagging their tails and poking at the mud with their bills. I can feel him coming nearer and nearer and my heart becomes glad.

but the meaning is less intellectual, more emotional and simple. The deliverance sought and won by the dying child is the same deliverance which rose before his imagination, [...] when once in the early dawn he heard, amid the noise of a crowd returning from some festival, this line out of an old village song, "Ferryman, take me to the other shore of the river." It may come at any moment of life, though the child discovers it in death, for it always comes at the moment when the "I", seeking no longer for gains that cannot be "assimilated with its spirit", is able to say, "All my work is thine".[12]

— W. B. Yeats, Preface, The Post Office, 1914.

His other works fuse lyrical flow and emotional rhythm into a tight focus on a core idea, a break from prior Bengali drama. Tagore sought "the play of feeling and not of action". In 1890 he released what is regarded as his finest drama: Visarjan (Sacrifice).[2] It is an adaptation of Rajarshi, an earlier novella of his. "A forthright denunciation of a meaningless [and] cruel superstitious rite[s]",[13] the Bengali originals feature intricate subplots and prolonged monologues that give play to historical events in seventeenth-century Udaipur. The devout Maharaja of Tripura is pitted against the wicked head priest Raghupati. His latter dramas were more philosophical and allegorical in nature; these included Dak Ghar. Another is Tagore's Chandalika (Untouchable Girl), which was modelled on an ancient Buddhist legend describing how Ananda, the Gautama Buddha's disciple, asks a tribal girl for water.[14]

In Raktakarabi ("Red" or "Blood Oleanders"), a kleptocrat king rules over the residents of Yaksha puri. He and his retainers exploit his subjects—who are benumbed by alcohol and numbered like inventory—by forcing them to mine gold for him. The naive maiden-heroine Nandini rallies her subject-compatriots to defeat the greed of the realm's sardar class—with the morally roused king's belated help. Skirting the "good-vs-evil" trope, the work pits a vital and joyous lèse majesté against the monotonous fealty of the king's varletry, giving rise to an allegorical struggle akin to that found in Animal Farm or Gulliver's Travels.[15] The original, though prized in Bengal, long failed to spawn a "free and comprehensible" translation, and its archaic and sonorous didacticism failed to attract interest from abroad.[16]

Chitrangada, Chandalika, and Shyama are other key plays that have dance-drama adaptations, which together are known as Rabindra Nritya Natya.

Short stories

Tagore began his career in short stories in 1877—when he was only sixteen—with "Bhikharini" ("The Beggar Woman").[17] With this, Tagore effectively invented the Bengali-language short story genre.[18] The four years from 1891 to 1895 are known as Tagore's "Sadhana" period (named for one of Tagore's magazines). This period was among Tagore's most fecund, yielding more than half the stories contained in the three-volume Galpaguchchha (or Golpoguchchho; "Bunch of Stories"), which itself is a collection of eighty-four stories.[17] Such stories usually showcase Tagore's reflections upon his surroundings, on modern and fashionable ideas, and on interesting mind puzzles (which Tagore was fond of testing his intellect with). Tagore typically associated his earliest stories (such as those of the "Sadhana" period) with an exuberance of vitality and spontaneity; these characteristics were intimately connected with Tagore's life in the common villages of, among others, Patisar, Shajadpur, and Shilaida while managing the Tagore family's vast landholdings.[17] There, he beheld the lives of India's poor and common people; Tagore thereby took to examining their lives with a penetrative depth and feeling that was singular in Indian literature up to that point.[19] In particular, such stories as "Kabuliwala" ("The Fruitseller from Kabul", published in 1892), "Kshudita Pashan" ("The Hungry Stones") (August 1895), and "Atottju"("The Runaway", 1895) typified this analytic focus on the downtrodden.[20]

In "Kabuliwala", Tagore speaks in first person as town-dweller and novelist who chances upon the Afghani seller. He attempts to distill the sense of longing felt by those long trapped in the mundane and hardscrabble confines of Indian urban life, giving play to dreams of a different existence in the distant and wild mountains: "There were autumn mornings, the time of year when kings of old went forth to conquest; and I, never stirring from my little corner in Calcutta, would let my mind wander over the whole world. At the very name of another country, my heart would go out to it ... I would fall to weaving a network of dreams: the mountains, the glens, the forest .... ".[21]

Many of the other Galpaguchchha stories were written in Tagore's Sabuj Patra period from 1914 to 1917, also named after one of the magazines that Tagore edited and heavily contributed to.[17]

Tagore's Galpaguchchha remains among the most popular fictional works in Bengali literature. Its continuing influence on Bengali art and culture cannot be overstated; to this day, it remains a point of cultural reference, and has furnished subject matter for numerous successful films and theatrical plays, and its characters are among the most well known to Bengalis.

The acclaimed film director Satyajit Ray based his film Charulata ("The Lonely Wife") on Nastanirh ("The Broken Nest"). This famous story has an autobiographical element to it, modelled to some extent on the relationship between Tagore and his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi. Ray has also made memorable films of other stories from Galpaguchchha, including Samapti, Postmaster and Monihara, bundling them together as Teen Kanya ("Three Daughters").

Atithi is another poignantly lyrical Tagore story which was made into a film of the same name by another noted Indian film director Tapan Sinha. Tarapada, a young Brahmin boy, catches a boat ride with a village zamindar. It turns out that he has run away from his home and has been wandering around ever since. The zamindar adopts him, and finally arranges a marriage to his own daughter. The night before the wedding Tarapada runs away again.

Strir Patra (The letter from the wife) was one of the earliest depictions in Bengali literature of bold emancipation of women. Mrinal is the wife of a typical Bengali middle-class man. The letter, written while she is traveling (which constitutes the whole story), describes her petty life and struggles. She finally declares that she will not return to her patriarchical home, stating Amio bachbo. Ei bachlum ("And I shall live. Here, I live").

In Haimanti, Tagore takes on the institution of Hindu marriage. He describes the dismal lifelessness of Bengali women after they are married off, hypocrisies plaguing the Indian middle class, and how Haimanti, a sensitive young woman, must — due to her sensitiveness and free spirit — sacrifice her life. In the last passage, Tagore directly attacks the Hindu custom of glorifying Sita's attempt of appeasing her husband Rama's doubts (as depicted in the epic Ramayana).

In Musalmanir Golpo, Tagore also examines Hindu-Muslim tensions, which in many ways embodies the essence of Tagore's humanism. On the other hand, Darpaharan exhibits Tagore's self-consciousness, describing a young man harboring literary ambitions. Though he loves his wife, he wishes to stifle her literary career, deeming it unfeminine. Tagore himself, in his youth, seems to have harbored similar ideas about women. Darpaharan depicts the final humbling of the man via his acceptance of his wife's talents.

Jibito o Mrito, as with many other Tagore stories, provides the Bengalis with one of their more widely used epigrams: Kadombini moriya proman korilo she more nai ("Kadombini died, thereby proved that she hadn't").

Novels

Among Tagore's works, his novels are among the least-acknowledged. These include Nastanirh (1901), Chokher Bali (1903), Noukadubi (1906), Gora (1910), Chaturanga (1916), Ghare Baire (1916), Shesher Kobita (1929), Jogajog (1929) and Char Adhyay (1934).

Ghare Baire or The Home and the World, which was also released as the film by Satyajit Ray (Ghare Baire, 1984) examines rising nationalistic feeling among Indians while warning of its dangers, clearly displaying Tagore's distrust of nationalism — especially when associated with a religious element.

In some sense, Gora shares the same theme, raising questions regarding the Indian identity. As with Ghare Baire, matters of self-identity, personal freedom, and religious belief are developed in the context of an involving family story and a love triangle.

Shesher Kobita (translated twice, as Last Poem and as Farewell Song) is his most lyrical novel, containing as it does poems and rhythmic passages written by the main character (a poet).

Though his novels remain under-appreciated, they have recently been given new attention through many movie adaptations by such film directors as Satyajit Ray, Tapan Sinha and Tarun Majumdar. The recent among these is a version of Chokher Bali] and Noukadubi (2011 film) directed by Lt. Rituparno Ghosh, which features Aishwariya Rai (in Chokher Bali). A favorite trope of these directors is to employ Rabindra Sangeet in the film adaptations' soundtracks.

Among Tagore's notable non-fiction books are Europe Jatrir Patro ("Letters from Europe") and Manusher Dhormo ("The Religion of Man").

Poetry

Internationally, Gitanjali (Bengali: গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection of poetry, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1913. Tagore was the first person (excepting Roosevelt) outside Europe to get the Nobel Prize. It was originally published in India in 1910.

The time that my journey takes is long and the way of it long.

I came out on the chariot of the first gleam of light, and pursued my voyage through the wildernesses of worlds leaving my track on many a star and planet.

It is the most distant course that comes nearest to thyself, and that training is the most intricate which leads to the utter simplicity of a tune.

The traveller has to knock at every alien door to come to his own, and one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end.

My eyes strayed far and wide before I shut them and said 'Here art thou!'

The question and the cry 'Oh, where?' melt into tears of a thousand streams and deluge the world with the flood of the assurance 'I am!'

Tagore's poetic style, which proceeds from a lineage established by 15th- and 16th-century Vaishnava poets, ranges from classical formalism to the comic, visionary, and ecstatic. He was influenced by the atavistic mysticism of Vyasa and other rishi-authors of the Upanishads, the Bhakti-Sufi mystic Kabir, and Ramprasad Sen.[23] Tagore's most innovative and mature poetry embodies his exposure to Bengali rural folk music, which included mystic Baul ballads such as those of the bard Lalon.[24][25] These, rediscovered and repopularised by Tagore, resemble 19th-century Kartābhajā hymns that emphasise inward divinity and rebellion against bourgeois bhadralok religious and social orthodoxy.[26][27] During his Shelaidaha years, his poems took on a lyrical voice of the moner manush, the Bāuls' "man within the heart" and Tagore's "life force of his deep recesses", or meditating upon the jeevan devata—the demiurge or the "living God within".[28] This figure connected with divinity through appeal to nature and the emotional interplay of human drama. Such tools saw use in his Bhānusiṃha poems chronicling the Radha-Krishna romance, which were repeatedly revised over the course of seventy years.[29][30]

Tagore reacted to the uptake of modernist and realist techniques in Bengali literature by making his own experiments in writing in the 1930s.[31] These include Africa and Camalia, among the better known of his latter poems. He occasionally wrote poems using Shadhu Bhasha, a Sanskritised dialect of Bengali; he later adopted a more popular dialect known as Cholti Bhasha. Other works include Manasi, Sonar Tori (Golden Boat), Balaka (Wild Geese, a name redolent of migrating souls),[32] and Purobi. Sonar Tori's most famous poem, dealing with the fleeting endurance of life and achievement, goes by the same name; hauntingly it ends: Shunno nodir tire rohinu poŗi / Jaha chhilo loe gêlo shonar tori—"all I had achieved was carried off on the golden boat—only I was left behind." Gitanjali (গীতাঞ্জলি) is Tagore's best-known collection internationally, earning him his Nobel.[33]

The year 1893 AD was the turn of the century in the Bangla calendar. It was the Bangla year 1300. Tagore wrote a poem then. Its name was ‘The year 1400’. In that poem, Tagore was appealing to a new future poet, yet to be born. He urged in that poem to remember Tagore while he was reading it. He addressed it to that unknown poet who was reading it a century later.

Tagore's poetry has been set to music by composers: Arthur Shepherd's triptych for soprano and string quartet, Alexander Zemlinsky's famous Lyric Symphony, Josef Bohuslav Foerster's cycle of love songs, Gertrude Price Wollner's song "Poem,"[34] Leoš Janáček's famous chorus "Potulný šílenec" ("The Wandering Madman") for soprano, tenor, baritone, and male chorus—JW 4/43—inspired by Tagore's 1922 lecture in Czechoslovakia which Janáček attended, and Garry Schyman's "Praan", an adaptation of Tagore's poem "Stream of Life" from Gitanjali. The latter was composed and recorded with vocals by Palbasha Siddique to accompany Internet celebrity Matt Harding's 2008 viral video.[35] In 1917 his words were translated adeptly and set to music by Anglo-Dutch composer Richard Hageman to produce a highly regarded art song: "Do Not Go, My Love". The second movement of Jonathan Harvey's "One Evening" (1994) sets an excerpt beginning "As I was watching the sunrise ..." from a letter of Tagore's, this composer having previously chosen a text by the poet for his piece "Song Offerings" (1985).[36]

|

|

Song VII of Gitanjali:

|

আমার এ গান ছেড়েছে তার |

Amar e gan chheŗechhe tar shôkol ôlongkar |

Tagore's free-verse translation:

My song has put off her adornments.

She has no pride of dress and decoration.

Ornaments would mar our union; they would come

between thee and me; their jingling would drown thy whispers.

My poet's vanity dies in shame before thy sight.

O master poet, I have sat down at thy feet.

Only let me make my life simple and straight,

like a flute of reed for thee to fill with music.[37]

"Klanti" (ক্লান্তি; "Weariness"):

|

ক্লান্তি আমার ক্ষমা করো প্রভু, |

Klanti amar khôma kôro probhu, |

Gloss by Tagore scholar Reba Som:

Forgive me my weariness O Lord

Should I ever lag behind

For this heart that this day trembles so

And for this pain, forgive me, forgive me, O Lord

For this weakness, forgive me O Lord,

If perchance I cast a look behind

And in the day's heat and under the burning sun

The garland on the platter of offering wilts,

For its dull pallor, forgive me, forgive me O Lord.[38]

Songs (Rabindra Sangeet)

At the time of his death, Tagore was both the most prolific composer and songwriter in history, with 2,230 songs to his credit. His songs are known as rabindrasangit ("Tagore Song"), which merges fluidly into his literature, most of which—poems or parts of novels, stories, or plays alike—were lyricised. Influenced by the thumri style of Hindustani music, they ran the entire gamut of human emotion, ranging from his early dirge-like Brahmo devotional hymns to quasi-erotic compositions.[39] They emulated the tonal colour of classical ragas to varying extents. Some songs mimicked a given raga's melody and rhythm faithfully; others newly blended elements of different ragas.[40] Yet about nine-tenths of his work was not bhanga gaan, the body of tunes revamped with "fresh value" from select Western, Hindustani, Bengali folk and other regional flavours "external" to Tagore's own ancestral culture.[28] Scholars have attempted to gauge the emotive force and range of Hindustani ragas:

The pathos of the purabi raga reminded Tagore of the evening tears of a lonely widow, while kanara was the confused realization of a nocturnal wanderer who had lost his way. In bhupali he seemed to hear a voice in the wind saying 'stop and come hither'. Paraj conveyed to him the deep slumber that overtook one at night's end.[28]

Regarding the terminology of "Rabindrasangeet," it is believed that on December 27, 1931, Dhurjatiprasad Mukhopadhyay wrote an essay titled “রবীন্দ্রনাথের সংগীত” (Rabindranath’s Music) for Tagore’s 70th birth anniversary, where the term “Rabindrasangeet” was used for the first time. In January 1935, Kanak Das’s recording P11792, featuring “মনে রবে কিনা রবে আমারে” (“Whether or not I remain in your recollection”) and “কাছে যবে ছিল পাশে হল না যাওয়া” (“When you were near, I couldn’t reach you”), first used “Rabindrasangeet” on the label. [42]

In 1971, Amar Shonar Bangla became the national anthem of Bangladesh. It was written — ironically — to protest the 1905 Partition of Bengal along communal lines: cutting off the Muslim-majority East Bengal from Hindu-dominated West Bengal was to avert a regional bloodbath. Tagore saw the partition as a cunning plan to stop the independence movement, and he aimed to rekindle Bengali unity and tar communalism. Jana Gana Mana was written in shadhu-bhasha, a Sanskritised register of Bengali, and is the first of five stanzas of a Brahmo hymn Bharot Bhagyo Bidhata that Tagore composed. It was first sung in 1911 at a Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress and was adopted in 1950 by the Constituent Assembly of the Republic of India as its national anthem. Tagore thus became the only person ever to have written the national anthems of two nations.

The Sri Lanka's National Anthem was inspired by his work.[44][45][46]

For Bengalis, the songs' appeal, stemming from the combination of emotive strength and beauty described as surpassing even Tagore's poetry, was such that the Modern Review observed that "[t]here is in Bengal no cultured home where Rabindranath's songs are not sung or at least attempted to be sung ... Even illiterate villagers sing his songs". A. H. Fox Strangways of The Observer introduced non-Bengalis to rabindrasangit in The Music of Hindostan, calling it a "vehicle of a personality ... [that] go behind this or that system of music to that beauty of sound which all systems put out their hands to seize."[47]

Tagore influenced sitar maestro Vilayat Khan and sarodiyas Buddhadev Dasgupta and Amjad Ali Khan.[40] His songs are widely popular and undergird the Bengali ethos to an extent perhaps rivalling Shakespeare's impact on the English-speaking world[48].[citation needed][who?] It is said that his songs are the outcome of five centuries of Bengali literary churning and communal yearning[49].[citation needed] Dhan Gopal Mukerji has said that these songs transcend the mundane to the aesthetic and express all ranges and categories of human emotion. The poet gave voice to all—big or small, rich or poor. The poor Ganges boatman and the rich landlord air their emotions in them. They birthed a distinctive school of music whose practitioners can be fiercely traditional: novel interpretations have drawn severe censure in both West Bengal and Bangladesh[50].[citation needed]

Digitization of Rabindrasangeet

Popular Rabindrasangeet has been digitized and featured on Phalguni Mookhopadhayay’s YouTube channel as part of Brainware University’s "Celebrating Tagore" initiative, launched on May 9, 2023. This project promotes Rabindranath Tagore's cultural heritage by releasing 100 selected songs, translated and sung by Mookhopadhayay, along with detailed anecdotes, appreciations, blogs, critical essays, and research papers, making Tagore’s works accessible globally.[51]

Furthermore, Saregama has produced an impressive 16,000 renditions of Rabindrasangeet. Among these, there are over ten cherished recordings where Tagore himself lent his voice to classics such as "Tobu Mone Rekho" and "Jana Gana Mana." The collection also showcases performances by renowned singers from the past, including Pankaj Mallick, Debabrata Biswas, Suchitra Mitra, Hemanta Mukherjee, and Chinmoy Chatterjee. [52]

Filmography

- Lyrics

- Nijere Haraye Khuji (1972)[citation needed]

Art works

At age sixty, Tagore took up drawing and painting; successful exhibitions of his many works — which made a debut appearance in Paris upon encouragement by artists he met in the south of France[54] — were held throughout Europe. Tagore — who likely exhibited protanopia ("color blindness"), or partial lack of (red-green, in Tagore's case) colour discernment — painted in a style characterised by peculiarities in aesthetic and colouring style. Nevertheless, Tagore took to emulating numerous styles, including scrimshaw by the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein.[55]

[...] Surrounded by several painters Rabindranath had always wanted to paint. Writing and music, play writing and acting came to him naturally and almost without training, as it did to several others in his family, and in even greater measure. But painting eluded him. Yet he tried repeatedly to master the art and there are several references to this in his early letters and reminiscence. In 1900 for instance, when he was nearing forty and already a celebrated writer, he wrote to Jagadishchandra Bose, "You will be surprised to hear that I am sitting with a sketchbook drawing. Needless to say, the pictures are not intended for any salon in Paris, they cause me not the least suspicion that the national gallery of any country will suddenly decide to raise taxes to acquire them. But, just as a mother lavishes most affection on her ugliest son, so I feel secretly drawn to the very skill that comes to me least easily.‟ He also realized that he was using the eraser more than the pencil, and dissatisfied with the results he finally withdrew, deciding it was not for him to become a painter.[56]

Tagore also had an artist's eye for his own handwriting, embellishing the cross-outs and word layouts in his manuscripts with simple artistic leitmotifs.

Rabindra Chitravali, a 2011 four-volume book set edited by noted art historian R. Siva Kumar, for the first time makes the paintings of Tagore accessible to art historians and scholars of Rabindranth with critical annotations and comments It also brings together a selection of Rabindranath's own statements and documents relating to the presentation and reception of his paintings during his lifetime.[57]

The Last Harvest : Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore was an exhibition of Rabindranath Tagore's paintings to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore. It was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, India and organized with NGMA Delhi as the nodal agency. It consisted of 208 paintings drawn from the collections of Visva Bharati and the NGMA and presented Tagore's art in a very comprehensive way. The exhibition was curated by Art Historian R. Siva Kumar. Within the 150th birth anniversary year it was conceived as three separate but similar exhibitions, and travelled simultaneously in three circuits. The first selection was shown at Museum of Asian Art, Berlin,[58] Asia Society, New York,[59] National Museum of Korea,[60] Seoul, Victoria and Albert Museum,[61] London, The Art Institute of Chicago,[62] Chicago, Petit Palais,[63] Paris, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna, Rome, National Visual Arts Gallery (Malaysia),[64] Kuala Lumpur, McMichael Canadian Art Collection,[65] Ontario, National Gallery of Modern Art,[66] New Delhi.

See also

- List of works by Rabindranath Tagore

- Adaptations of works of Rabindranath Tagore in film and television

- An Artist in Life — biography by Niharranjan Ray

- Rabindranath Tagore (film) — a biographical documentary by Satyajit Ray.

- Political views of Rabindranath Tagore

- Celebrating Tagore

Citations

- ^ Lago 1977, p. 15.

- ^ a b Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 123.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, p. 321.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, pp. 416–417.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, pp. 318–321.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, pp. 385–386.

- ^ Lifton & Wiesel 1997, p. 349.

- ^ Tagore & Mukerjea 1914, p. 68.

- ^ Tagore & Mukerjea 1914, pp. v–vi.

- ^ Ayyub 1980, p. 48.

- ^ Tagore & Chakravarty 1961, p. 124.

- ^ Ray 2007, pp. 147–148.

- ^ O'Connell 2008.

- ^ a b c d Chakravarty 1961, p. 45.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 265.

- ^ Chakravarty 1961, pp. 45–46

- ^ Chakravarty 1961, p. 46

- ^ Chakravarty 1961, pp. 48–49

- ^ Prasad & Sarkar 2008, p. 125.

- ^ Roy 1977, p. 201.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 94.

- ^ Urban 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Urban 2001, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Urban 2001, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Ghosh 2011.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 281.

- ^ Dutta & Robinson 1995, p. 192.

- ^ Tagore, Stewart & Twichell 2003, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Cohen, Aaron (1987). International Encyclopedia of Women Composers. New York: Books & Music USA Inc. p. 764. ISBN 0961748516.

- ^ McGrath, Charles (8 July 2008). "A Private Dance? Four Million Web Fans Say No". The New York Times.

- ^ Harvey 1999, pp. 59, 90.

- ^ Tagore 1952, p. 5.

- ^ Tagore, Alam & Chakravarty 2011, p. 323.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 94.

- ^ a b Dasgupta 2001.

- ^ Som 2010, p. 38.

- ^ "History of Harmony: Unravelling the Roots of Rabindrasangeet". Celebrating Tagore - The Man, The Poet and The Musician. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ "Tabu mone rekho". tagoreweb.in (in Bengali). Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- ^ de Silva, K. M.; Wriggins, Howard (1988). J. R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka: a Political Biography - Volume One: The First Fifty Years. University of Hawaii Press. p. 368. ISBN 0-8248-1183-6.

- ^ "Man of the series: Nobel laureate Tagore". The Times of India. Times News Network. 3 April 2011.

- ^ "How Tagore inspired Sri Lanka's national anthem". IBN Live. 8 May 2012. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 359.

- ^ mishra, kishan (May 22, 2023). "Rabindranath Tagore biography : A Journey through the Life and Legacy of a Visionary Poet". kishandiaries. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ "Rabindranath Tagore biography : A Journey through the Life and Legacy of a Visionary Poet". kishan diaries. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ mishra, kishan (May 22, 2023). "Rabindranath Tagore biography : A Journey through the Life and Legacy of a Visionary Poet". kishandiaries.

- ^ "Embracing Tagore: A Celebration of the Legendary Poet, Musician, Philosopher, and Visionary". Celebrating Tagore - The Man, The Poet and The Musician. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ "Old songs of Tagore, Nazrul digitised for first time". The Times of India. 2016-06-03. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ Dyson 2001.

- ^ Tagore, Dutta & Robinson 1997, p. 222.

- ^ Dyson 2001.

- ^ Kumar 2011.

- ^ "Rabindra Chitravali". National Commemoration of 150th Birth Anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore. Archived from the original on 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Kalender". Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ Current Exhibitions Upcoming Exhibitions Past Exhibitions. "Rabindranath Tagore: The Last Harvest". Asia Society. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Special Exhibitions". National Museum of Korea. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Painter". Victoria and Albert Museum. 6 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Art Institute Showcases Paintings and Drawings By Eminent Indian Poet and Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore" (PDF). The Art Institute of Chicago (Press release).

- ^ "Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)". Le Petit Palais. 2012-03-11. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "Welcome to High Commission of India, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia)". Indian High Commission Malaysia. Archived from the original on 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "The Last Harvest: Paintings by Rabindranath Tagore". McMichael Canadian Art Collection. 2012-07-15. Archived from the original on 2012-12-08. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ^ "The Last Harvest" (PDF). National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi.

References

- Ayyub, A. S. (1980), Tagore's Quest, Papyrus, OCLC 557456321.

- Chakravarty, A. (1961), A Tagore Reader, Beacon Press, ISBN 0-8070-5971-4.

- Dasgupta, A. (2001), "Rabindra-Sangeet as a Resource for Indian Classical Bandishes", Parabaas, retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Dutta, K.; Robinson, A. (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-14030-4.

- Dyson, K. K. (2001), "Rabindranath Tagore and His World of Colours", Parabaas, retrieved 26 November 2009.

- Ghosh, B. (2011), "Inside the World of Tagore's Music", Parabaas, retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Harvey, J. (1999), In Quest of Spirit: Thoughts on Music, University of California Press, archived from the original on 6 May 2001, retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Kumar, R. Siva (2011), The Last Harvest: Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore, Mapin Publishing, ISBN 978-8189995614.

- Lago, M. (1977), Rabindranath Tagore, Boston: Twayne Publishers, ISBN 978-0-8057-6242-6.

- Lifton, B. J.; Wiesel, E. (1997), The King of Children: The Life and Death of Janusz Korczak, St. Martin's Griffin, ISBN 978-0-312-15560-5.

- O'Connell, K. M. (2008), "Red Oleanders (Raktakarabi) by Rabindranath Tagore—A New Translation and Adaptation: Two Reviews", Parabaas, retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Prasad, A. N.; Sarkar, B. (2008), Critical Response To Indian Poetry in English, Sarup and Sons, ISBN 978-81-7625-825-8.

- Ray, M. K. (2007), Studies on Rabindranath Tagore, vol. 1, Atlantic, ISBN 978-81-269-0308-5, retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Roy, B. K. (1977), Rabindranath Tagore: The Man and His Poetry, Folcroft Library Editions, ISBN 978-0-8414-7330-0.

- Som, R. (2010), Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and His Song, Viking, ISBN 978-0-670-08248-3, OL 23720201M.

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1952), Collected Poems and Plays of Rabindranath Tagore, Macmillan Publishing, ISBN 978-0-02-615920-3.

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2011), Alam, F.; Chakravarty, R. (eds.), The Essential Tagore, Harvard University Press, p. 323, ISBN 978-0-674-05790-6.

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1914), The Post Office, translated by Mukerjea, D., London: Macmillan.

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1997), Dutta, K.; Robinson, A. (eds.), Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-16973-6.

- Tagore, Rabindranath (2003), Rabindranath Tagore: Lover of God, Lannan Literary Selections, translated by Stewart, T. K.; Twichell, C., Copper Canyon Press, ISBN 978-1-55659-196-9.

- Tagore, Rabindranath (1961), Chakravarty, A. (ed.), A Tagore Reader, Beacon Press, ISBN 978-0-8070-5971-5.

- Urban, H. B. (2001), Songs of Ecstasy: Tantric and Devotional Songs from Colonial Bengal, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-513901-3.

- Som, KK (2001), "Rabindranath Tagore and his World of Colours", Parabaas, retrieved 2006-04-01.

Further reading

- Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi (2011). Rabindranath Tagore: an interpretation. New Delhi: Viking, Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0670084555.

- Chakravarty, Radha (2016). Novelist Tagore: Gender and Modernity in Selected Texts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-92885-9.

- Kulkarni, Prafull D. (2010). The Dramatic World of Rabindranath Tagore. Creative Publications. ISBN 978-81-906717-2-9