This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

Alsace

Elsàss (Alemannic German) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "Elsässisches Fahnenlied" (German)[1] (English: "Song of the Alsatian Flag") | |

| |

| Country | France |

| Territorial collectivity | European Collectivity of Alsace |

| Prefecture | Strasbourg |

| Departments | |

| Area | |

• Total | 8,280 km2 (3,200 sq mi) |

| Population (Jan. 2021)[3] | |

• Total | 1,919,745 |

| • Density | 230/km2 (600/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Alsatian |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €67.748 billion (2022) |

| • Per capita | €35,800 (2022) |

| ISO 3166 code | FR-A |

| Part of a series on |

| Alsace |

|---|

|

|

Alsace (/ælˈsæs/,[5] US also /ælˈseɪs, ˈælsæs/;[6][7] French: [alzas] ; Low Alemannic German/Alsatian: Elsàss [ˈɛlsɑs]; German: Elsass (German spelling before 1996: Elsaß) [ˈɛlzas] ⓘ; Latin: Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In January 2021, it had a population of 1,919,745.[3] Alsatian culture is characterized by a blend of German and French influences.[8]

Until 1871, Alsace included the area now known as the Territoire de Belfort, which formed its southernmost part. From 1982 to 2016, Alsace was the smallest administrative région in metropolitan France, consisting of the Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin departments. Territorial reform passed by the French Parliament in 2014 resulted in the merger of the Alsace administrative region with Champagne-Ardenne and Lorraine to form Grand Est. On 1 January 2021, the departments of Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin merged into the new European Collectivity of Alsace but remained part of the region Grand Est.

Alsatian is an Alemannic dialect closely related to Swabian, although since World War II most Alsatians primarily speak French. Internal and international migration since 1945 has also changed the ethnolinguistic composition of Alsace. For more than 300 years, from the Thirty Years' War to World War II, the political status of Alsace was heavily contested between France and various German states in wars and diplomatic conferences. The economic and cultural capital of Alsace, as well as its largest city, is Strasbourg, which sits on the present German international border. The city is the seat of several international organizations and bodies.

Etymology

The name Alsace can be traced to the Old High German Ali-saz or Elisaz, meaning "foreign domain".[9] An alternative explanation is from a Germanic Ell-sass, meaning "seated on the Ill",[10] a river in Alsace.

History

In prehistoric times, Alsace was inhabited by nomadic hunters. Part of the province of Germania Superior in the Roman Empire, the area went on to become a diffuse border region between the French and the German cultures and languages. Long a center of the German-speaking world, after the end of the Thirty Years' War, southern Alsace was annexed by France in 1648, with most of the remainder conquered later in the century. In contrast to other parts of France, Protestants were permitted to practise their faith in Alsace even after the Edict of Fontainebleau of 1685 that abolished their privileges in the rest of France.

After the 1870–71 Franco-Prussian War, Alsace was annexed by Germany and became a part of the 1871 unified German Empire as a formal "Emperor's Land". After World War I the victorious Allies detached it from Germany and the province became part of the Third French Republic. Having been occupied and annexed by Germany during World War II, it was returned to France by the Allies at the end of World War II.

Pre-Roman Alsace

The presence of hominids in Alsace can be traced back 600,000 years.[11] By 4000 BCE farming, in the form of Linear Pottery culture, arrived in the region from the Danube and the Hungarian plain. The culture was characterized by "timber longhouse settlements and incised pottery ... favoring floodplain edge situations for their permanent villages ... [and] small clearings in the forest" for their crops and animals."[12]

By 100 BCE Germanic peoples, including eventually the Suebi and other tribes under Ariovistus, had begun to intrude into areas along the upper Rhine and Danube long settled by Celtic Gauls. Alsace itself had come to be occupied by the Triboci, a Germanic tribe allied with Ariovistus.[13]

Roman Alsace

In response to the threat posted by Ariovistus, the Aedui, a Celtic tribe allied to Rome, appealed to the Roman Senate and Julius Caesar for aid. In 58 BCE, after negotiations with Ariovistus failed, Julius Caesar routed the Suebi at the foot of the Vosges near what became Cernay in southern Alsace.[14][15] There followed a "long period of security ... for the Gauls along the middle and upper Rhine."[14]

From the time of Augustus to the early fifth century AD, the area of Alsace was incorporated into the Roman province of Germania Superior.[16] As a border province, the Romans built fortifications and military camps, many of which, including Argentoratum (Strasbourg), evolved into modern towns and cities.[17]

Alemannic and Frankish Alsace

In 357 CE, Germanic tribes attempted to conquer Alsace but they were rebuffed by the Romans.[11] With the decline of the Roman Empire, Alsace became the territory of the Germanic Alemanni. The Alemanni were agricultural people, and their Germanic language formed the basis of modern-day dialects spoken along the Upper Rhine (Alsatian, Alemannian, Swabian, Swiss). Clovis and the Franks defeated the Alemanni during the 5th century AD, culminating with the Battle of Tolbiac, and Alsace became part of the Kingdom of Austrasia. Under Clovis' Merovingian successors the inhabitants were Christianized. Alsace remained under Frankish control until the Frankish realm, following the Oaths of Strasbourg of 842, was formally dissolved in 843 at the Treaty of Verdun; the grandsons of Charlemagne divided the realm into three parts. Alsace formed part of the Middle Francia, which was ruled by the eldest grandson Lothar I.

Lothar died early in 855 and his realm was divided into three parts. The part known as Lotharingia, or Lorraine, was given to Lothar's son. The rest was shared between Lothar's brothers Charles the Bald (ruler of the West Frankish realm) and Louis the German (ruler of the East Frankish realm). The Kingdom of Lotharingia was short-lived, however, becoming the stem duchy of Lorraine in Eastern Francia after the Treaty of Ribemont in 880. Alsace was united with the other Alemanni east of the Rhine into the stem duchy of Swabia.

Alsace within the Holy Roman Empire

At about this time, the surrounding areas experienced recurring fragmentation and reincorporations among a number of feudal secular and ecclesiastical lordships, a common process in the Holy Roman Empire. Alsace experienced great prosperity during the 12th and 13th centuries under Hohenstaufen emperors.

Frederick I set up Alsace as a province (a procuratio, not a provincia) to be ruled by ministeriales, a non-noble class of civil servants. The idea was that such men would be more tractable and less likely to alienate the fief from the crown out of their own greed. The province had a single provincial court (Landgericht) and a central administration with its seat at Hagenau. Frederick II designated the Bishop of Strasbourg to administer Alsace, but the authority of the bishop was challenged by Count Rudolf of Habsburg, who received his rights from Frederick II's son Conrad IV. Strasbourg began to grow to become the most populous and commercially important town in the region.

In 1262, after a long struggle with the ruling bishops, its citizens gained the status of free imperial city. A stop on the Paris-Vienna-Orient trade route, as well as a port on the Rhine route linking southern Germany and Switzerland to the Netherlands, England and Scandinavia, it became the political and economic center of the region. Cities such as Colmar and Hagenau also began to grow in economic importance and gained a kind of autonomy within the "Décapole" (or "Zehnstädtebund"), a federation of ten free towns.

Though little is known about the early history of the Jews of Alsace, there is a lot of information from the 12th century onwards. They were successful as moneylenders and had the favor of the Emperor.[18] As in much of Europe, the prosperity of Alsace was brought to an end in the 14th century by a series of harsh winters, bad harvests, and the Black Death. These hardships were blamed on Jews, leading to the pogroms of 1336 and 1339. In 1349, Jews of Alsace were accused of poisoning the wells with plague, leading to the massacre of thousands of Jews during the Strasbourg pogrom.[19] Jews were subsequently forbidden to settle in the town. An additional natural disaster was the Rhine rift earthquake of 1356, one of Europe's worst which made ruins of Basel. Prosperity returned to Alsace under Habsburg administration during the Renaissance.

Holy Roman Empire central power had begun to decline following years of imperial adventures in Italian lands, often ceding hegemony in Western Europe to France, which had long since centralized power. France began an aggressive policy of expanding eastward, first to the rivers Rhône and Meuse, and when those borders were reached, aiming for the Rhine. In 1299 the French proposed a marriage alliance between Blanche (sister of Philip IV of France) and Rudolf (son of Albert I of Germany), with Alsace to be the dowry; however, the deal never came off. In 1307, the town of Belfort was first chartered by the Counts of Montbéliard. During the next century, France was to be militarily shattered by the Hundred Years' War, which prevented for a time any further tendencies in this direction. After the conclusion of the war, France was again free to pursue its desire to reach the Rhine and in 1444 a French army appeared in Lorraine and Alsace. It took up winter quarters, demanded the submission of Metz and Strasbourg and launched an attack on Basel.

In 1469, following the Treaty of St. Omer, Upper Alsace was sold by Archduke Sigismund of Austria to Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Although Charles was the nominal landlord, taxes were paid to Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor. The latter was able to use this tax and a dynastic marriage to his advantage to gain back full control of Upper Alsace (apart from the free towns, but including Belfort) in 1477 when it became part of the demesne of the Habsburg family, who were also rulers of the empire. The town of Mulhouse joined the Swiss Confederation in 1515, where it was to remain until 1798.

By the time of the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, Strasbourg was a prosperous community, and its inhabitants accepted Protestantism in 1523. Martin Bucer was a prominent Protestant reformer in the region. His efforts were countered by the Roman Catholic Habsburgs who tried to eradicate heresy in Upper Alsace. As a result, Alsace was transformed into a mosaic of Catholic and Protestant territories. On the other hand, Mömpelgard (Montbéliard) to the southwest of Alsace, belonging to the Counts of Württemberg since 1397, remained a Protestant enclave in France until 1793.

German Land within the Kingdom of France

This situation prevailed until 1639, when most of Alsace was conquered by France to keep it out of the hands of the Spanish Habsburgs, who by secret treaty in 1617 had gained a clear road to their valuable and rebellious possessions in the Spanish Netherlands, the Spanish Road. Beset by enemies and seeking to gain a free hand in Hungary, the Habsburgs sold their Sundgau territory (mostly in Upper Alsace) to France in 1646, which had occupied it, for the sum of 1.2 million Thalers. When hostilities were concluded in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia, most of Alsace was recognized as part of France, although some towns remained independent. The treaty stipulations regarding Alsace were complex. Although the French king gained sovereignty, existing rights and customs of the inhabitants were largely preserved. France continued to maintain its customs border along the Vosges mountains where it had been, leaving Alsace more economically oriented to neighbouring German-speaking lands. The German language remained in use in local administration, in schools, and at the (Lutheran) University of Strasbourg, which continued to draw students from other German-speaking lands. The 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau, by which the French king ordered the suppression of French Protestantism, was not applied in Alsace. France did endeavour to promote Catholicism. Strasbourg Cathedral, for example, which had been Lutheran from 1524 to 1681, was returned to the Catholic Church. However, compared to the rest of France, Alsace enjoyed a climate of religious tolerance.

France consolidated its hold with the 1679 Treaties of Nijmegen, which brought most remaining towns under its control. France seized Strasbourg in 1681 in an unprovoked action. These territorial changes were recognised in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick that ended the War of the Grand Alliance. But Alsace still contained islands of territory nominally under the sovereignty of German princes and an independent city-state at Mulhouse. These enclaves were established by law, prescription and international consensus.[20]

From French Revolution to the Franco-Prussian War

Freiheit Gleichheit Brüderlichk. od. Tod (Liberty Equality Fraternity or Death)

Tod den Tyranen (Death to Tyrants)

Heil den Völkern (Long live the Peoples)

The year 1789 brought the French Revolution and with it the first division of Alsace into the départements of Haut- and Bas-Rhin. Alsatians played an active role in the French Revolution. On 21 July 1789, after receiving news of the Storming of the Bastille in Paris, a crowd of people stormed the Strasbourg city hall, forcing the city administrators to flee and putting symbolically an end to the feudal system in Alsace. In 1792, Rouget de Lisle composed in Strasbourg the Revolutionary marching song "La Marseillaise" (as Marching song for the Army of the Rhine), which later became the anthem of France. "La Marseillaise" was played for the first time in April of that year in front of the mayor of Strasbourg Philippe-Frédéric de Dietrich. Some of the most famous generals of the French Revolution also came from Alsace, notably Kellermann, the victor of Valmy, Kléber, who led the armies of the French Republic in Vendée, and Westermann, who also fought in the Vendée.

Mulhouse (a city in southern Alsace), which had been part of Switzerland since 1466, joined France in 1798.[11]

At the same time, some Alsatians were in opposition to the Jacobins and sympathetic to the restoration of the monarchy pursued by the invading forces of Austria and Prussia who sought to crush the nascent revolutionary republic. Many of the residents of the Sundgau made "pilgrimages" to places like Mariastein Abbey, near Basel, in Switzerland, for baptisms and weddings. When the French Revolutionary Army of the Rhine was victorious, tens of thousands fled east before it. When they were later permitted to return (in some cases not until 1799), it was often to find that their lands and homes had been confiscated. These conditions led to emigration by hundreds of families to newly vacant lands in the Russian Empire in 1803–4 and again in 1808. A poignant retelling of this event based on what Goethe had personally witnessed can be found in his long poem Hermann and Dorothea.

In response to the "hundred day" restoration of Napoleon I of France in 1815, Alsace along with other frontier provinces of France was occupied by foreign forces from 1815 to 1818,[21] including over 280,000 soldiers and 90,000 horses in Bas-Rhin alone. This had grave effects on trade and the economy of the region since former overland trade routes were switched to newly opened Mediterranean and Atlantic seaports.

The population grew rapidly, from 800,000 in 1814 to 914,000 in 1830 and 1,067,000 in 1846. The combination of economic and demographic factors led to hunger, housing shortages and a lack of work for young people. Thus, it is not surprising that people left Alsace, not only for Paris – where the Alsatian community grew in numbers, with famous members such as Georges-Eugène Haussmann – but also for more distant places like Russia and the Austrian Empire, to take advantage of the new opportunities offered there: Austria had conquered lands in Eastern Europe from the Ottoman Empire and offered generous terms to colonists as a way of consolidating its hold on the new territories. Many Alsatians also began to sail to the United States, settling in many areas from 1820 to 1850.[22] In 1843 and 1844, sailing ships bringing immigrant families from Alsace arrived at the port of New York. Some settled in Texas and Illinois, many to farm or to seek success in commercial ventures: for example, the sailing ships Sully (in May 1843) and Iowa (in June 1844) brought families who set up homes in northern Illinois and northern Indiana. Some Alsatian immigrants were noted for their roles in 19th-century American economic development.[23] Others ventured to Canada to settle in southwestern Ontario, notably Waterloo County.

Alsatian Jews

In contrast to the rest of France, the Jews in Alsace had not been expelled during the Middle Ages. By 1790, the Jewish population of Alsace was approximately 22,500, about 3% of the provincial population. They were highly segregated and subject to long-standing antisemitic regulations. They maintained their own customs, Yiddish language, and historic traditions within the tightly knit ghettos; they adhered to Jewish law. Jews were barred from most cities and instead lived in villages. They concentrated in trade, services, and banking. They financed about a third of the mortgages in Alsace. Official tolerance grew during the French Revolution, with full emancipation in 1791. However, local antisemitism also increased and Napoleon turned hostile in 1806, imposing a one-year moratorium on all debts owed to Jews.[24] In the 1830–1870 era, most Jews moved to the cities, where they integrated and acculturated, as antisemitism sharply declined. By 1831, the state began paying salaries to official rabbis, and in 1846 a special legal oath for Jews was discontinued. Antisemitic local riots occasionally occurred, especially during the Revolution of 1848. The merger of Alsace into Germany in 1871–1918 lessened antisemitic violence.[25] The constitution of the Reichsland of 1911 reserved one seat in the first chamber of the Landtag for a representative of the Jewish Consistory of Alsace–Lorraine (besides two seats respectively for the two main Christian denominations).

Struggle between France and united Germany

We Germans who know Germany and France know better what is good for the Alsatians than the unfortunates themselves. In the perversion of their French life they have no exact idea of what concerns Germany.

The Franco-Prussian War, which started in July 1870, saw France defeated in May 1871 by the Kingdom of Prussia and other German states. The end of the war led to the unification of Germany. Otto von Bismarck annexed Alsace and northern Lorraine to the new German Empire in 1871. France ceded more than 90% of Alsace and one-fourth of Lorraine, as stipulated in the treaty of Frankfurt; Belfort, the largest Alsatian town south of Mulhouse, remained French. Unlike other member states of the German federation, which had governments of their own, the new Imperial territory of Alsace–Lorraine was under the sole authority of the Kaiser, administered directly by the imperial government in Berlin. Between 100,000 and 130,000 Alsatians (of a total population of about a million and a half) chose to remain French citizens and leave Reichsland Elsaß–Lothringen, many of them resettling in French Algeria as Pieds-Noirs. Only in 1911 was Alsace–Lorraine granted some measure of autonomy, which was manifested also in a flag and an anthem (Elsässisches Fahnenlied). In 1913, however, the Saverne Affair (French: Incident de Saverne) showed the limits of this new tolerance of the Alsatian identity.

During the First World War, to avoid ground fights between brothers, many Alsatians served as sailors in the Kaiserliche Marine and took part in the Naval mutinies that led to the abdication of the Kaiser in November 1918, which left Alsace–Lorraine without a nominal head of state. The sailors returned home and tried to found an independent republic. While Jacques Peirotes, at this time deputy at the Landrat Elsass–Lothringen and just elected mayor of Strasbourg, proclaimed the forfeiture of the German Empire and the advent of the French Republic, a self-proclaimed government of Alsace–Lorraine declared its independence as the "Republic of Alsace–Lorraine". French troops entered Alsace less than two weeks later to quash the worker strikes and remove the newly established Soviets and revolutionaries from power. With the arrival of the French soldiers, many Alsatians and local Prussian/German administrators and bureaucrats cheered the re-establishment of order.[28]

Although U.S. President Woodrow Wilson had insisted that the région was self-ruling by legal status, as its constitution had stated it was bound to the sole authority of the Kaiser and not to the German state, France would allow no plebiscite, as granted by the League of Nations to some eastern German territories at this time, because the French regarded the Alsatians as Frenchmen liberated from German rule. Germany ceded the region to France under the Treaty of Versailles.

Policies forbidding the use of German and requiring French were promptly introduced.[29] In order not to antagonize the Alsatians, the region was not subjected to some legal changes that had occurred in the rest of France between 1871 and 1919, such as the 1905 French law on the separation of Church and State.

Alsace–Lorraine was occupied by Germany in 1940 during the Second World War. Although it was never formally annexed, Alsace–Lorraine was incorporated into the Greater German Reich, which had been restructured into Reichsgaue. Alsace was merged with Baden, and Lorraine with the Saarland, to become part of a planned Westmark. During the war, 130,000 young men from Alsace and Lorraine were conscripted into the German armies against their will (malgré-nous). There were some volunteers for the Waffen SS.,[30] although they were outnumbered by conscripts of the 1926–1927 classes. Thirty of said Waffen SS were involved in the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre (29 conscripts, one volunteer). A third of the malgré-nous perished on the Eastern front. In July 1944, 1500 malgré-nous were released from Soviet captivity and sent to Algiers, where they joined the Free French Forces.

After World War II

Today, the territory is in certain areas subject to some laws that are significantly different from the rest of France, which is known as the local law.

In more recent years, the Alsatian language is again being promoted by local, national and European authorities as an element of the region's identity. Alsatian is taught in schools (but is not mandatory) as one of the regional languages of France. German is also taught as a foreign language in local kindergartens and schools. There is a growing network of schools proposing full immersion in Alsatian dialect and in Standard German, called ABCM-Zweisprachigkeit (ABCM -> French acronym for "Association for Bilingualism in the Classroom from Kindergarten onwards", Zweisprachigkeit -> German for "Bilingualism"). However, the Constitution of France still requires that French be the only official language of the Republic.

Timeline

| Year(s) | Event | Ruled by | Official or common language |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5400–4500 BC | Bandkeramiker/Linear Pottery cultures | — | Unknown |

| 2300–750 BC | Bell Beaker cultures | — | Proto-Celtic spoken |

| 750–450 BC | Hallstatt culture early Iron Age (early Celts) | — | None; Old Celtic spoken |

| 450–58 BC | Celts/Gauls firmly secured in entire Gaul, Alsace; trade with Greece is evident (Vix) | Celts/Gauls | None; Gaulish variety of Celtic widely spoken |

| 58 / 44 BC– AD 260 |

Alsace and Gaul conquered by Caesar, provinciated to Germania Superior | Roman Empire | Latin; Gallic widely spoken |

| 260–274 | Postumus founds breakaway Gallic Empire | Gallic Empire | Latin, Gallic |

| 274–286 | Rome reconquers the Gallic Empire, Alsace | Roman Empire | Latin, Gallic, Germanic (only in Argentoratum) |

| 286–378 | Diocletian divides the Roman Empire into Western and Eastern sectors | Roman Empire | |

| around 300 | Beginning of Germanic migrations to the Roman Empire | Roman Empire | |

| 378–395 | The Visigoths rebel, precursor to waves of German, and Hun invasions | Roman Empire | Alamannic Incursions |

| 395–436 | Death of Theodosius I, causing a permanent division between Western and Eastern Rome | Western Roman Empire | |

| 436–486 | Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire | Roman Tributary of Gaul | Alamannic |

| 486–511 | Lower Alsace conquered by the Franks | Frankish Realm | Old Frankish, Latin; Alamannic |

| 531–614 | Upper Alsace conquered by the Franks | Frankish Realm | |

| 614–795 | Totality of Alsace to the Frankish Kingdom | Frankish Realm | |

| 795–814 | Charlemagne begins reign, Charlemagne crowned Emperor of the Romans on 25 December 800 | Frankish Empire | Old Frankish; Frankish and Alamannic |

| 814 | Death of Charlemagne | Carolingian Empire | Old Frankish; Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 847–870 | Treaty of Verdun gives Alsace and Lotharingia to Lothar I | Middle Francia (Carolingian Empire) | Frankish; Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 870–889 | Treaty of Mersen gives Alsace to East Francia | East Francia (German Kingdom of the Carolingian Empire) | Frankish, Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 889–962 | Carolingian Empire breaks up into five Kingdoms, Magyars and Vikings periodically raid Alsace | Kingdom of Germany | Frankish and Alamannic varieties of Old High German |

| 962–1618 | Otto I crowned Holy Roman Emperor | Holy Roman Empire | Old High German, Middle High German, Modern High German; Alamannic and Franconian German dialects |

| 1618–1674 | Louis XIII annexes portions of Alsace during the Thirty Years' War | Holy Roman Empire | German; Alamannic and Franconian dialects (Alsatian) |

| 1674–1871 | Louis XIV annexes the rest of Alsace during the Franco-Dutch War, establishing full French sovereignty over the region | Kingdom of France | Officially French (Alsatian and German tolerated and spoken by an estimated 85%-90% of the population) |

| 1871–1918 | Franco-Prussian War causes French cession of Alsace to German Empire | German Empire | German; German/Alsatian (86.8% - 1,492,347 people), French (11.5% - 198,318 people), Italian (1.1% - 18,750 people), German and a second language (0.4% - 7,485 people), Polish (0.1% - 1,410 people). Statistics from 1871. Over time, French declined to 10.9% |

| 1919–1940 | Treaty of Versailles causes German cession of Alsace to France | France | French; Alsatian, French, German |

| 1940–1944 | Nazi Germany conquers Alsace, establishing Gau Baden-Elsaß | Nazi Germany | German; Alsatian, French, German |

| 1945–present | French control | France | French; French and Alsatian German (declining minority language) |

Geography

Topography

Alsace has an area of 8,283 km2, making it the smallest région of metropolitan France. It is almost four times longer than it is wide, corresponding to a plain between the Rhine in the east and the Vosges mountains in the west.

It includes the départements of Haut-Rhin and Bas-Rhin (known previously as Sundgau and Nordgau). It borders Germany on the north and the east, Switzerland and Franche-Comté on the south and Lorraine on the west.

Several valleys are also found in the région. Its highest point is the Grand Ballon in Haut-Rhin, which reaches a height of 1,424 m (4,672 ft). It contains many forests, primarily in the Vosges and in Bas-Rhin (Haguenau Forest).

The ried lies along the Rhine.

Geology

Alsace is the part of the plain of the Rhine located at the west of the Rhine, on its left bank. It is a rift or graben, from the Oligocene epoch, associated with its horsts: the Vosges and the Black Forest.

The Jura Mountains, formed by slip (induced by the alpine uplift) of the Mesozoic cover on the Triassic formations, goes through the area of Belfort.

Climate

Alsace has an oceanic climate at low altitude and a continental climate at high altitude. There is fairly low precipitation because the Vosges protect it from the west. The city of Colmar has a sunny microclimate; it is the second driest city in France, with an annual precipitation of around 700 mm (28 in), making it ideal for vin d'Alsace (Alsatian wine).

Governance

Since 2021, Alsace has been a territorial collectivity called the European Collectivity of Alsace (collectivité européenne d'Alsace).

Administrative divisions

The European Collectivity of Alsace is divided into 2 departmental constituencies (circonscriptions départementales), 9 departmental arrondissements, 40 cantons, and 880 communes.

- Arrondissement of Haguenau-Wissembourg

- Arrondissement of Molsheim

- Arrondissement of Saverne

- Arrondissement of Sélestat-Erstein

- Arrondissement of Strasbourg

- Arrondissement of Altkirch

- Arrondissement of Colmar-Ribeauvillé

- Arrondissement of Guebwiller

- Arrondissement of Mulhouse

- Arrondissement of Thann-Guebwiller

Society

Demographics

Alsace's population increased to 1,919,745 in 2021.[3] It has regularly increased over time, except in wartime and shortly after the German annexation of 1871 (when many Alsatians who had opted to keep their French citizenship emigrated to France), by both natural growth and immigration. High population growth during the post-WW2 economic boom of the Trente Glorieuses ended after the 1973 oil crisis. Demographic growth picked up again in the 1990s and 2000s, but by the 2010s Alsace entered a new period of slow demographic growth.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: French and German censuses (1806-1871),[31] (1876–2021),[32][3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Immigration

At the 2018 census, 69.9% of the inhabitants of Alsace were natives of Alsace, 16.0% were born in the rest of Metropolitan France, 0.5% were born in Overseas France, and 13.7% were born in foreign countries.[33] Nearly 44% of the immigrants come from Europe, in particular from Germany (natives of Germany residing in Alsace where housing is cheaper), Italy, Portugal and Serbia.[34][35] Since 2008, the number of Turkish immigrants living in Alsace has declined, whereas the number of Maghreban immigrants has risen less than the number of European immigrants.[36][34][35] The fastest growing groups of immigrants are those from Asia and from sub-Saharan Africa.[36][34][35]

| Census | Born in Alsace | Born in the rest of Metropolitan France |

Born in Overseas France |

Born in foreign countries with French citizenship at birth[a] |

Immigrants[b] | ||||

| 2018 | 69.9% | 16.0% | 0.5% | 2.2% | 11.6% | ||||

| from Europe | from the Maghreb[c] | from Turkey | from the rest of the world | ||||||

| 5.1% | 2.6% | 1.5% | 2.4% | ||||||

| 2013 | 71.1% | 15.4% | 0.4% | 2.3% | 10.8% | ||||

| from Europe | from the Maghreb[c] | from Turkey | from the rest of the world | ||||||

| 4.8% | 2.5% | 1.6% | 2.0% | ||||||

| 2008 | 71.8% | 15.3% | 0.4% | 2.3% | 10.3% | ||||

| from Europe | from the Maghreb[c] | from Turkey | from the rest of the world | ||||||

| 4.5% | 2.4% | 1.6% | 1.8% | ||||||

| 1999 | 73.6% | 15.4% | 0.4% | 2.1% | 8.5% | ||||

| from Europe | from the Maghreb[c] | from Turkey | from the rest of the world | ||||||

| 4.2% | 1.9% | 1.3% | 1.1% | ||||||

| 1990 | 75.9% | 13.4% | 0.3% | 2.4% | 7.9% | ||||

| 1982 | 76.8% | 12.5% | 0.3% | 2.6% | 7.8% | ||||

| 1975 | 78.3% | 11.6% | 0.2% | 2.6% | 7.3% | ||||

| 1968 | 81.7% | 9.8% | 0.1% | 2.8% | 5.6% | ||||

| ^a Persons born abroad of French parents, such as Pieds-Noirs and children of French expatriates. ^b An immigrant is by French definition a person born in a foreign country and who did not have French citizenship at birth. Note that an immigrant may have acquired French citizenship since moving to France, but is still listed as an immigrant in French statistics. On the other hand, persons born in France with foreign citizenship (the children of immigrants) are not listed as immigrants. ^c Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria | |||||||||

| Source: INSEE[33][34][35][37][36][38] | |||||||||

Religion

Alsace is generally seen as the most religious of all the French regions. Most of the Alsatian population is Roman Catholic, but, largely because of the region's German heritage, a significant Protestant community also exists: today, the EPCAAL (a Lutheran church) is France's second largest Protestant church, also forming an administrative union (UEPAL) with the much smaller Calvinist EPRAL. Unlike the rest of France, the Local law in Alsace–Moselle still provides for the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 and the organic articles, which provides public subsidies to the Roman Catholic, Lutheran, and Calvinist churches, as well as to Jewish synagogues; religion classes in one of these faiths are compulsory in public schools. The divergence in policy from the French majority is because the region was part of Imperial Germany when the 1905 law separating the French church and state was instituted (for a more comprehensive history, see Alsace–Lorraine). Controversy erupts periodically on the appropriateness of that legal disposition, as well as on the exclusion of other religions from the arrangement.

Following the Protestant Reformation, promoted by the local reformer Martin Bucer, the principle of cuius regio, eius religio led to a certain amount of religious diversity in the highlands of northern Alsace. Landowners, who as "local lords" had the right to decide the religion that was allowed on their land, were eager to entice populations from the more attractive lowlands to settle and develop their property. Many accepted without discrimination Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, Jews and Anabaptists. Multiconfessional villages appeared, particularly in the region of Alsace bossue. Alsace became one of the French regions boasting a thriving Jewish community and the only region with a noticeable Anabaptist population. Philipp Jakob Spener who founded Pietism was born in Alsace. The schism of the Amish under the lead of Jacob Amman from the Mennonites occurred in 1693 in Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines. The strongly Catholic Louis XIV tried in vain to drive them from Alsace. When Napoleon imposed military conscription without religious exception, most emigrated to the American continent.

In 1707, the simultaneum forced many Reformed and Lutheran church buildings to also allow Catholic services. About 50 such "simultaneous churches" still exist in modern Alsace, but with the Catholic church's general lack of priests, they tend to hold Catholic services only occasionally.

Culture

Alsace historically was part of the Holy Roman Empire and the German realm of culture. Since the 17th century, the region has passed between German and French control numerous times, resulting in a cultural blend. German traits remain in the more traditional, rural parts of the culture, such as the cuisine and architecture, whereas modern institutions are totally dominated by French culture.

Symbolism

Strasbourg

Strasbourg's arms are the colours of the shield of the Bishop of Strasbourg (a band of red on a white field, also considered an inversion of the arms of the diocese) at the end of a revolt of the burghers during the Middle Ages who took their independence from the teachings of the Bishop. It retains its power over the surrounding area.

Flags

There is controversy around the recognition of the Alsatian flag. The authentic historical flag is the Rot-un-Wiss; Red and White are commonly found on the coat of arms of Alsatian cities (Strasbourg, Mulhouse, Sélestat...)[40] and of many Swiss cities, especially in Basel's region. The German region Hesse uses a flag similar to the Rot-un-Wiss. As it underlines the Germanic roots of the region, it was replaced in 1949 by a new "Union jack-like" flag representing the union of the two départements. It has, however, no real historical relevance. It has been since replaced again by a slightly different one, also representing the two départements. With the purpose of "Francizing" the region, the Rot-un-Wiss has not been recognized by Paris. Some overzealous statesmen have called it a Nazi invention – while its origins date back to the 11th century and the Red and White banner[41] of Gérard de Lorraine (aka. d'Alsace). The Rot-un-Wiss flag is still known as the real historical emblem of the region by most of the population and the départements' parliaments and has been widely used during protests against the creation of a new "super-region" gathering Champagne-Ardennes, Lorraine and Alsace, namely on Colmar's statue of liberty.[42]

Language

Although German dialects were spoken in Alsace for most of its history, the dominant language in Alsace today is French.

The traditional language of the région is Alsatian, an Alemannic dialect of Upper German spoken on both sides of the Rhine and closely related to Swiss German. Some Frankish dialects of West Central German are also spoken in "Alsace Bossue" and in the extreme north of Alsace. As is customary for regional languages in France, neither Alsatian nor the Frankish dialects have any form of official status, although both are now recognized as languages of France and can be chosen as subjects in lycées.

Although Alsace has been part of France multiple times in the past, the region had no direct connection with the French state for several centuries. From the end of the Roman Empire (5th century) to the French annexation (17th century), Alsace was politically part of the German world.

During the Lutheran Reform, the towns of Alsace were the first to adopt the German language as their official language instead of Latin. It was in Strasbourg that German was first used for the liturgy. It was also in Strasbourg that the first German Bible was published in 1466.

From the annexation of Alsace by France in the 17th century and the language policy of the French Revolution up to 1870, knowledge of French in Alsace increased considerably. With the education reforms of the 19th century, the middle classes began to speak and write French well. The French language never really managed, however, to win over the masses, the vast majority of whom continued to speak their German dialects and write in German (which we would now call "standard German").[citation needed]

Between 1870 and 1918, Alsace was annexed by the German Empire in the form of an imperial province or Reichsland, and the mandatory official language, especially in schools, became High German. French lost ground to such an extent that it has been estimated that only 2% of the population spoke French fluently, and only 8% had some knowledge of it (Maugue, 1970).

After 1918, French was the only language used in schools, particularly primary schools. After much argument and discussion and after many temporary measures, a memorandum was issued by Vice-Chancellor Pfister in 1927 and governed education in primary schools until 1939.

During a reannexation by Germany (1940–1945), High German was reinstated as the language of education. The population was forced to speak German and 'French' family names were Germanized. Following the Second World War, the 1927 regulation was not reinstated, and the teaching of German in primary schools was suspended by a provisional rectorial decree, which was supposed to enable French to regain lost ground. The teaching of German became a major issue, however, as early as 1946. After World War II, the French government pursued, in line with its traditional language policy, a campaign to suppress the use of German as part of a wider Francization campaign. The local German dialect was rendered a backward regional "Germanic" dialect not being attached to German.[43]

In 1951, Article 10 of the Deixonne Law (Loi Deixonne) on the teaching of local languages and dialects made provision for Breton, Basque, Catalan and old Provençal but not for Corsican, Dutch (West Flemish) or Alsatian in Alsace and Moselle. However, in a Decree of 18 December 1952, supplemented by an Order of 19 December of the same year, optional teaching of the German language was introduced in elementary schools in communes in which the language of habitual use was the Alsatian dialect.

In 1972, the Inspector General of German, Georges Holderith, obtained authorization to reintroduce German into 33 intermediate classes on an experimental basis. This teaching of German, referred to as the Holderith Reform, was later extended to all pupils in the last two years of elementary school. This reform is still largely the basis of German teaching (but not Alsatian) in elementary schools today.

It was not until 9 June 1982, with the Circulaire sur la langue et la culture régionales en Alsace (Memorandum on regional language and culture in Alsace) issued by the Vice-Chancellor of the Académie Pierre Deyon, that the teaching of German in primary schools in Alsace really began to be given more official status. The Ministerial Memorandum of 21 June 1982, known as the Circulaire Savary, introduced financial support, over three years, for the teaching of regional languages in schools and universities. This memorandum was, however, implemented in a fairly lax manner.

Both Alsatian and Standard German were for a time banned from public life (including street and city names, official administration, and educational system). Though the ban has long been lifted and street signs today are often bilingual, Alsace–Lorraine is today predominantly French in language and culture. Few young people speak Alsatian today, although there do still exist one or two enclaves in the Sundgau region where some older inhabitants cannot speak French, and where Alsatian is still used as the mother tongue. A related Alemannic German survives on the opposite bank of the Rhine, in Baden, and especially in Switzerland. However, while French is the major language of the region, the Alsatian dialect of French is heavily influenced by German and other languages such as Yiddish in phonology and vocabulary.

This situation has spurred a movement to preserve the Alsatian language, which is perceived as endangered, a situation paralleled in other régions of France, such as Brittany or Occitania. Alsatian is now taught in French high schools. Increasingly, French is the only language used at home and at work, and a growing number of people have a good knowledge of standard German as a foreign language learned in school.

The constitution of the Fifth Republic states that French alone is the official language of the Republic. However, Alsatian, along with other regional languages, are recognized by the French government in the official list of languages of France.

Although the French government signed the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in 1992, it never ratified the treaty and therefore no legal basis exists for any of the regional languages in France.[44] However, visitors to Alsace can see indications of renewed political and cultural interest in the language – in Alsatian signs appearing in car-windows and on hoardings, and in new official bilingual street signs in Strasbourg and Mulhouse.

A 1999 INSEE survey, included in the 1999 Census, the majority of the population in Alsace speak French as their first language, 39.0% (or 500,000 people) of the population speak Alsatian, 16.2% (or 208,000 people) speak German, 75,200 people speak English (or 5.9%) and 27,600 people speak Italian.[45]

The survey counted 548,000 adult speakers of Alsatian in France, making it the second most-spoken regional language in the country (after Occitan). Like all regional languages in France, however, the transmission of Alsatian is on the decline. While 39% of the adult population of Alsace speak Alsatian, only one in four children speak it, and only one in ten children uses it regularly.

Architecture

The traditional habitat of the Alsatian lowland, like in other regions of Germany and Northern Europe, consists of houses constructed with walls in timber framing and cob and roofing in flat tiles. This type of construction is abundant in adjacent parts of Germany and can be seen in other areas of France, but their particular abundance in Alsace is owed to several reasons:

- The proximity to the Vosges where the wood can be found.

- During periods of war and bubonic plague, villages were often burned down, so to prevent the collapse of the upper floors, ground floors were built of stone and upper floors built in half-timberings to prevent the spread of fire.

- During most of its history, a great part of Alsace was flooded by the Rhine every year. Half-timbered houses were easy to knock down and to move around during those times (a day was necessary to move it and a day to rebuild it in another place).

However, half-timbering was found to increase the risk of fire, which is why from the 19th century, it began to be rendered. In recent times, villagers started to paint the rendering white in accordance with Beaux-Arts movements. To discourage this, the region's authorities gave financial grants to the inhabitants to paint the rendering in various colours, in order to return to the original style and many inhabitants accepted (more for financial reasons than by firm belief).[citation needed]

Cuisine

Alsatian cuisine, somewhat based on German culinary traditions, is marked by the use of pork in various forms. It is perhaps mostly known for the region's wines and beers. Traditional dishes include baeckeoffe, flammekueche, choucroute, and fleischnacka. Southern Alsace, also called the Sundgau, is characterized by carpe frite (that also exists in Yiddish tradition).

Food

The festivities of the year's end involve the production of a great variety of biscuits and small cakes called bredela as well as pain d'épices (gingerbread cakes) which are baked around Christmas time. The Kugelhupf is also popular in Alsace, and the Christstollen during the Christmas season.[46]

A gastronomic symbol of the région is the Choucroute, a local variety of Sauerkraut. The word Sauerkraut in Alsatian has the form sûrkrût, same as in other southwestern German dialects, and means "sour cabbage" as its Standard German equivalent. This word was included into the French language as choucroute. To make it, the cabbage is finely shredded, layered with salt and juniper and left to ferment in wooden barrels. Sauerkraut can be served with poultry, pork, sausage or even fish. Traditionally it is served with Strasbourg sausage or frankfurters, bacon, smoked pork or smoked Morteau or Montbéliard sausages, or a selection of other pork products. Served alongside are often roasted or steamed potatoes or dumplings.

Alsace is also well known for its foie gras made in the region since the 17th century. Additionally, Alsace is known for its fruit juices and mineral waters.

Wines

Alsace is an important wine-producing région. Vins d'Alsace (Alsace wines) are mostly white. Alsace produces some of the world's most noted dry rieslings and is the only region in France to produce mostly varietal wines identified by the names of the grapes used (wine from Burgundy is also mainly varietal, but not normally identified as such), typically from grapes also used in Germany. The most notable example is Gewurztraminer.

Beers

Alsace is also the main beer-producing region of France, thanks primarily to breweries in and near Strasbourg. These include those of Fischer, Karlsbräu, Kronenbourg, and Heineken International. Hops are grown in Kochersberg and in northern Alsace. Schnapps is also traditionally made in Alsace, but it is in decline because home distillers are becoming less common and the consumption of traditional, strong, alcoholic beverages is decreasing.

In tales

The stork is a main feature of Alsace and was the subject of many legends told to children. The bird practically disappeared around 1970, but re-population efforts are continuing. They are mostly found on roofs of houses, churches and other public buildings in Alsace.

The Easter Bunny was first mentioned in Georg Franck von Franckenau's De ovis paschalibus (About Easter eggs) in 1682 referring to an Alsace tradition of an Easter Hare bringing Easter eggs.

The term "Alsatia"

"Alsatia", the Latin form of Alsace's name, entered the English language as "a lawless place" or "a place under no jurisdiction" prior to the 17th century as a reflection of the British perception of the region at that time. It was used into the 20th century as a term for a ramshackle marketplace, "protected by ancient custom and the independence of their patrons". The word is still in use in the 21st century among the English and Australian judiciaries to describe a place where the law cannot reach: "In setting up the Serious Organised Crime Agency, the state has set out to create an Alsatia – a region of executive action free of judicial oversight," Lord Justice Sedley in UMBS v SOCA 2007.[47]

Derived from the above, "Alsatia" was historically a cant term for the area near Whitefriars, London, which was for a long time a sanctuary. It is first known in print in the title of The Squire of Alsatia, a 1688 play written by Thomas Shadwell.

Economy

According to the Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE), Alsace had a gross domestic product of 44.3 billion euros in 2002. With a GDP per capita of €24,804, it is the second région of France, after only Île-de-France, and 68% of Alsatian jobs are in the services, and 25% are in industry, which makes Alsace one of France's most industrialised régions.

Alsace is a région of varied economic activity, including:

- viticulture (mostly along the Route des Vins d'Alsace between Marlenheim and Thann)

- hop harvesting and brewing (half of French beer is produced in Alsace, especially in the vicinity of Strasbourg, notably in Schiltigheim, Hochfelden, Saverne and Obernai)

- forestry development

- automobile industry (Mulhouse and Molsheim, home town of Bugatti Automobiles)

- life sciences, as part of the trinational BioValley

- tourism

- potassium chloride (until the late 20th century) and potash mining

Alsace has many international ties and 35% of firms are foreign companies (notably German, Swiss, American, Japanese, and Scandinavian).

Tourism

Having been early and always densely populated, Alsace is famous for its high number of picturesque villages, churches and castles and for the various beauties of its three main towns, in spite of severe destructions suffered throughout five centuries of wars between France and Germany.

Alsace is furthermore famous for its vineyards (especially along the 170 km of the Route des Vins d'Alsace from Marlenheim to Thann) and the Vosges mountains with their thick and green forests and picturesque lakes.

- Old towns of Strasbourg, Colmar, Sélestat, Guebwiller, Saverne, Obernai, Thann

- Smaller cities and villages: Molsheim, Rosheim, Riquewihr, Ribeauvillé, Kaysersberg, Wissembourg, Neuwiller-lès-Saverne, Marmoutier, Rouffach, Soultz-Haut-Rhin, Bergheim, Hunspach, Seebach, Turckheim, Eguisheim, Neuf-Brisach, Ferrette, Niedermorschwihr and the gardens of the blue house in Uttenhoffen[48]

- Churches (as main sights in otherwise less remarkable places): Thann, Andlau, Murbach, Ebersmunster, Niederhaslach, Sigolsheim, Lautenbach, Epfig, Altorf, Ottmarsheim, Domfessel, Niederhaslach, Marmoutier and the fortified church at Hunawihr

- Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg

- Other castles: Ortenbourg and Ramstein (above Sélestat), Hohlandsbourg, Fleckenstein, Haut-Barr (above Saverne), Saint-Ulrich (above Ribeauvillé), Lichtenberg, Wangenbourg, the three Castles of Eguisheim, Pflixbourg, Wasigenstein, Andlau, Grand Geroldseck, Wasenbourg

- Cité de l'Automobile museum in Mulhouse

- Cité du train museum in Mulhouse

- The EDF museum in Mulhouse

- Ungersheim's "écomusée" (open-air museum) and "Bioscope" (leisure park about the environment, closed since September 2012)

- Musée historique in Haguenau, largest museum in Bas-Rhin outside Strasbourg

- Bibliothèque humaniste in Sélestat, one of the oldest public libraries in the world

- Christmas markets in Kaysersberg, Strasbourg, Mulhouse and Colmar

- Departmental Centre of the History of Families (CDHF) in Guebwiller

- The Maginot Line: Ouvrage Schoenenbourg

- Mount Ste Odile

- Route des Vins d'Alsace (Alsace Wine Route)

- Mémorial d'Alsace–Lorraine in Schirmeck

- Natzweiler-Struthof, the only German concentration camp on French territory during WWII

- Famous mountains: Massif du Donon, Grand Ballon, Petit Ballon, Ballon d'Alsace, Hohneck, Hartmannswillerkopf

- National park: Parc naturel des Vosges du Nord

- Regional park: Parc naturel régional des Ballons des Vosges (south of the Vosges)

Transportation

Roads

Most major car journeys are made on the A35 autoroute, which links Saint-Louis on the Swiss border to Lauterbourg on the German border.

The A4 toll road (towards Paris) begins 20 km (12 mi) northwest of Strasbourg and the A36 toll road towards Lyon, begins 10 km (6.2 mi) west from Mulhouse.

Spaghetti junctions (built in the 1970s and 1980s) are prominent in the comprehensive system of motorways in Alsace, especially in the outlying areas of Strasbourg and Mulhouse. These cause a major buildup of traffic and are the main sources of pollution in the towns, notably in Strasbourg where the motorway traffic of the A35 was 170,000 per day in 2002.

At present, plans are being considered for building a new dual carriageway west of Strasbourg, which would reduce the buildup of traffic in that area by picking up north and southbound vehicles and getting rid of the buildup outside Strasbourg. The line plans to link up the interchange of Hœrdt to the north of Strasbourg, with Innenheim in the southwest. The opening is envisaged at the end of 2011, with an average usage of 41,000 vehicles a day. Estimates of the French Works Commissioner however, raised some doubts over the interest of such a project, since it would pick up only about 10% of the traffic of the A35 at Strasbourg. Paradoxically, this reversed the situation of the 1950s. At that time, the French trunk road left of the Rhine not been built, so that traffic would cross into Germany to use the Karlsruhe-Basel Autobahn.

To add to the buildup of traffic, the neighbouring German state of Baden-Württemberg has imposed a tax on heavy-goods vehicles using their Autobahnen. Thus, a proportion of the HGVs travelling from north Germany to Switzerland or southern Alsace bypasses the A5 on the Alsace-Baden-Württemberg border and uses the untolled French A35 instead.

Trains

TER Alsace is the rail network serving Alsace. Its network is articulated around the city of Strasbourg. It is one of the most developed rail networks in France, financially sustained partly by the French railroad SNCF, and partly by the région Alsace.

Because the Vosges are surmountable only by the Col de Saverne and the Belfort Gap, it has been suggested that Alsace needs to open up and get closer to France in terms of its rail links. Developments already under way or planned include:

- the TGV Est (Paris – Strasbourg) had its first phase brought into service in June 2007, bringing down the Strasbourg-Paris trip from 4 to 2 hours 20 minutes, and further reducing it to 1h 50m after the completion of the second phase in 2016.

- the TGV Rhin-Rhône between Dijon and Mulhouse (opened in 2011)

- a tram-train system in Mulhouse (2011)

- an interconnection with the German InterCityExpress, as far as Kehl (expected 2016)

However, the abandoned Maurice-Lemaire tunnel towards Saint-Dié-des-Vosges was rebuilt as a toll road.

Waterways

Port traffic of Alsace exceeds 15 million tonnes, of which about three-quarters is centred on Strasbourg, which is the second busiest French fluvial harbour. The enlargement plan of the Rhône–Rhine Canal, intended to link up the Mediterranean Sea and Central Europe (Rhine, Danube, North Sea and Baltic Sea) was abandoned in 1998 for reasons of expense and land erosion, notably in the Doubs valley.

Air traffic

There are two international airports in Alsace:

- the international airport of Strasbourg in Entzheim

- the international EuroAirport Basel-Mulhouse-Freiburg, which is the seventh largest French airport in terms of traffic

Strasbourg is also two hours away by road from one of the largest European airports, Frankfurt Main, and 2 hours 30 minutes from Charles de Gaulle Airport through the direct TGV service, stopping in Terminal 2.

Cycling network

Crossed by three EuroVelo routes

- the EuroVelo 5 (Via Francigena from London to Rome/Brindisi),

- the EuroVelo 6 (Véloroute des fleuves from Nantes to Budapest (H)) and

- the EuroVelo 15 (Véloroute Rhin / Rhine cycle route from Andermatt (CH) to Rotterdam (NL)).

Alsace is the most bicycle-friendly region of France,[citation needed] with 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) of cycle routes. The network is of a very good standard and well signposted. All the towpaths of the canals in Alsace (canal des houillères de la Sarre, canal de la Marne au Rhin, canal de la Bruche, canal du Rhône au Rhin) are tarred.

Notable people

The following is a selection of people born in Alsace who have been particularly influential or successful in their respective fields.

Arts

- Jean Arp

- Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, born in Colmar in 1834[49]

- Théodore Deck

- Gustave Doré

- Sébastien Érard

- Jean-Jacques Henner

- Philip James de Loutherbourg

- Master of the Drapery Studies

- Marcel Marceau

- Sam Marx, born as Simon Marx in Mertzwiller in 1859[50]

- Charles Munch

- Claude Rich

- Martin Schongauer

- Marie Tussaud

- Tomi Ungerer

- Émile Waldteufel

- Jean-Jacques Waltz (aka Hansi)

- Cora Wilburn

- William Wyler

Business

- Automobiles Ettore Bugatti

- Thierry Mugler

- Schlumberger brothers

- André Koechlin

- Léopold Louis-Dreyfus

- Jean-Georges Vongerichten

Literature

- Sebastian Brant, who was born in Strasbourg in 1457 or 1458[51]

- August Stöber

- Gottfried von Strassburg

Military

- Alfred Dreyfus, who was born in Mulhouse in 1859[52]

- François Christophe de Kellermann

- Jean-Baptiste Kléber

- Jacques Paul Klein

- François Joseph Lefebvre

- Jean Rapp

Nobility

Religion

- Martin Bucer

- Wolfgang Capito

- Charles de Foucauld

- Herrad of Landsberg

- Pope Leo IX

- Thomas Murner

- J. F. Oberlin

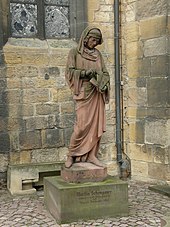

- Odile of Alsace

- Albert Schweitzer

- Philipp Spener

- Jakob Wimpfeling

- Mordecai Mokiach

Sciences

- Hans Bethe

- Charles Friedel

- Charles Frédéric Gerhardt

- Johann Hermann

- Alfred Kastler

- Erich Leo Lehmann

- Jean-Marie Lehn

- Wilhelm Philippe Schimper

- Charles Xavier Thomas

- Pierre Weiss

- Charles-Adolphe Wurtz

Sports

- Mehdi Baala

- Yann Ehrlacher

- Valérien Ismaël

- Sébastien Loeb

- Yvan Muller

- Thierry Omeyer

- Thomas Voeckler

- Arsène Wenger

Major communities

German original names in brackets if French names differ:

- Bischheim

- Colmar (Kolmar)

- Guebwiller (Gebweiler)

- Haguenau (Hagenau)

- Illkirch-Graffenstaden (Illkirch-Grafenstaden)

- Illzach

- Lingolsheim

- Mulhouse (Mülhausen)

- Saint-Louis (St. Ludwig)

- Saverne (Zabern)

- Schiltigheim

- Sélestat (Schlettstadt)

- Strasbourg (Straßburg)

- Wittenheim

Sister regions

There is an accord de coopération internationale between Alsace and the following regions:[53]

- Vest, Romania

- Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea

- Upper Austria, Austria

- Lower Silesia, Poland

- Quebec, Canada

- Jiangsu, China

- Moscow, Russia

See also

- 2014 Alsace single territorial collectivity referendum

- Miel d'Alsace

- Musée alsacien (Strasbourg)

- Route Romane d'Alsace

- German place names in Alsace

- Alsace independence movement

- Castroville, Texas

Notes

References

- ^ "Elsässisches Fahnenlied [Anthem of Alsace][+English translation]". YouTube. 14 April 2020.

- ^ "La géographie de l'Alsace". region.alsace. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Combined 2021 population of the departements of Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin: "Populations légales des départements en 2021". INSEE. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Alsace". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Alsace". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Alsace". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Leichtfried, Laura (23 February 2017). "Alsace: culturally not quite French, not quite German". British Council. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2021.

- ^ Bostock, John Knight; Kenneth Charles King; D. R. McLintock (1976). Kenneth Charles King, D. R. McLintock (ed.). A Handbook on Old High German Literature (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-19-815392-9.

- ^ Roland Kaltenbach: Le guide de l’Alsace, La Manufacture 1992, ISBN 2-7377-0308-5, page 36

- ^ a b c Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- ^ Bellwood, Peter (2005). First Farmers. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 77.

- ^ Cary, M.; Scullard, H.H. (1979). A History of Rome Down to the Reign of Constantine. London: MacMillan Education Ltd. p. 260.

- ^ a b Cary, M.; Scullard, H.H. (1979). A History of Rome Down to the Age of Constantine (third ed.). London: Macmillan Education Ltd. pp. 259–261.

- ^ Caesar, Julius (2000). Henderson, Jeffrey (ed.). The Galllic War, Book 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. pp. 46-87 (lines 31-54).

- ^ Sheperd, William (1929). Historical Atlas (seventh ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 38–39.

- ^ Cary, M.; Scullard, H.H. (1979). A History of Rome Down to the Reign of Constantine. London: MacMillan Education Ltd. pp. 336 and 458.

- ^ Wigoder, Geoffrey (1972). Jewish Art and Civilization. p. 62.

- ^ Sherman, Irwin W. (2006). The power of plagues. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 74. ISBN 1-55581-356-9.

- ^ Doyle, William (1989). The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-880493-2.

- ^ Veve, Thomas Dwight (1992). The Duke of Wellington and the British army of occupation in France, 1815–1818, pp. 20–21. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, United States.

- ^ "Cox.net". Archived from the original on 4 May 2006.

- ^ Ilgenweb.net Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Necheles, Ruth F. (1971). "The Abbé Grégoire and the Jews". Jewish Social Studies. 33 (2/3): 120–40. JSTOR 4466643. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Caron, Vicki (2005). "Alsace". In Levy, Richard S. (ed.). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. Vol. 1. Abc-Clio. pp. 13–16. ISBN 9781851094394.

- ^ "Full text of "Alsace–Lorraine since 1870"". New York, The Macmillan. 1919.

- ^ Remaking the Map of Europe by Jean Finot, The New York Times, 30 May 1915

- ^ "Archive video".

- ^ However, propaganda for elections was allowed to go with a German translation from 1919 to 2008.

- ^ Stéphane Courtois, Mark Kramer. Livre noir du Communisme: crimes, terreur, répression. Harvard University Press, 1999. p.323. ISBN 0-674-07608-7

- ^ EHESS. "Des villages de Cassini aux communes d'aujourd'hui". Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ INSEE. "Statistiques locales - Population municipale (historique depuis 1876)". Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ a b INSEE. "Données harmonisées des recensements de la population 1968–2018" (in French). Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d INSEE. "IMG1B - Population immigrée par sexe, âge et pays de naissance en 2018 - Département du Bas-Rhin (67)" (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d INSEE. "IMG1B - Population immigrée par sexe, âge et pays de naissance en 2018 - Département du Haut-Rhin (68)" (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ a b c INSEE. "IMG1B - Population immigrée par sexe, âge et pays de naissance en 2008" (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ INSEE. "IMG1B - Population immigrée par sexe, âge et pays de naissance en 2013 - Région d'Alsace (42)" (in French). Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ INSEE. "D_FD_IMG2 – Base France par départements – Lieux de naissance à l'étranger selon la nationalité" (in French). Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ [1] Géographie réligieuse: France

- ^ "Unser LandBrève histoire d'un drapeau alsacien". Unser Land. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ "Genealogie-bisval.net".

- ^ "Colmar : une statue de la Liberté en "Rot und Wiss"". France 3 Alsace. 16 November 2014.

- ^ von Polenz, Peter (1999). Deutsche Sprachgeschichte vom Spätmittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. Vol. Band III: 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin/New York. p. 165.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Charte européenne des langues régionales : Hollande nourrit la guerre contre le français". Le Figaro. 5 June 2015.

- ^ www.epsilon.insee.fr/jspui/bitstream/1/2294/1/cpar12_1.pdf, L'alsacien, deuxième langue régionale de France. INSEE. December 2002. p. 3.

- ^ "Les Christstollen de la vallée de Munster". 2009.

- ^ Lashmar, Paul (27 May 2007). "Law Lords slam crime agency for freezing UMBS payments". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Jardins de la ferme bleue – SehenswĂźrdigkeiten in Uttenhoffen, Elsa". beLocal.de. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ La famille paternelle des Marx Brothers (in French)

- ^ Zeydel, Edwin H. (1966). "Wann wurde Sebastian Brant geboren?". Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur. 95 (4): 319–320. ISSN 0044-2518. JSTOR 20655345.

- ^ "Birth certificate of Dreyfus, Alfred". culture.gouv.fr. Government of the French Republic. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Les Accords de coopération entre l'Alsace et..." (in French). Archived from the original on 3 January 2011.

Further reading

- Assall, Paul. Juden im Elsass. Zürich: Rio Verlag. ISBN 3-907668-00-6.

- Das Elsass: Ein literarischer Reisebegleiter. Frankfurt a. M.: Insel Verlag, 2001. ISBN 3-458-34446-2.

- Erbe, Michael (Hrsg.) Das Elsass: Historische Landschaft im Wandel der Zeiten. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag, 2002. ISBN 3-17-015771-X.

- Faber, Gustav. Elsass. München: Artemis-Cicerone Kunst- und Reiseführer, 1989.

- Fischer, Christopher J. Alsace to the Alsatians? Visions and Divisions of Alsatian Regionalism, 1870–1939 (Berghahn Books, 2010).

- Gerson, Daniel. Die Kehrseite der Emanzipation in Frankreich: Judenfeindschaft im Elsass 1778 bis 1848. Essen: Klartext, 2006. ISBN 3-89861-408-5.

- Herden, Ralf Bernd. Straßburg Belagerung 1870. Norderstedt: BoD, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8334-5147-8.

- Hummer, Hans J. Politics and Power in Early Medieval Europe: Alsace and the Frankish Realm, 600–1000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Kaeppelin, Charles E. R, and Mary L. Hendee. Alsace Throughout the Ages. Franklin, Pa: C. Miller, 1908.

- Lazer, Stephen A. State Formation in Early Modern Alsace, 1648–1789. Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2019. Archived 12 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Mehling, Marianne (Hrsg.) Knaurs Kulturführer in Farbe Elsaß. München: Droemer Knaur, 1984.

- Putnam, Ruth. Alsace and Lorraine: From Cæsar to Kaiser, 58 B.C.–1871 A.D. New York: 1915.

- Schreiber, Hermann. Das Elsaß und seine Geschichte, eine Kulturlandschaft im Spannungsfeld zweier Völker. Augsburg: Weltbild, 1996.

- Schwengler, Bernard. Le Syndrome Alsacien: d'Letschte? Strasbourg: Éditions Oberlin, 1989. ISBN 2-85369-096-2.

- Ungerer, Tomi. Elsass. Das offene Herz Europas. Straßburg: Édition La Nuée Bleue, 2004. ISBN 2-7165-0618-3.

- Vogler, Bernard and Hermann Lersch. Das Elsass. Morstadt: Éditions Ouest-France, 2000. ISBN 3-88571-260-1.

External links

- Official website of the Alsace regional council Archived 30 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Alsace : at the heart of Europe Archived 5 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Official French website (in English)

- Visit Alsace Official Alsace tourism website

- Rhine Online – life in southern Alsace and neighbouring Basel and Baden Wuerrtemburg

- Alsatourisme Archived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Tourism in Alsace (in French)

- Alsace.net: Directory of Alsatian Websites (in French)

- "Museums of Alsace" (in French)

- Churches and chapels of Alsace (pictures only) (in French)

- Medieval castles of Alsace (pictures only) (in French)

- "Organs of Alsace" (in French)

- The Alsatian Library of Mutual Credit (in French)

- The Alsatian Artists (in French)