Desi Sangye Gyatso (1653–1705) was the sixth regent (desi) of the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682) in the Ganden Phodrang government. He founded the School of Medicine and Astrology called Men-Tsee-Khang on Chagpori ('Iron Mountain') in 1694[1] and wrote the Blue Beryl (Blue Sapphire) treatise.[2][3] His name is sometimes written as Sangye Gyamtso[4] and Sans-rGyas rGya-mTsho[5]: 342, 351

By some erroneous accounts, Sangye Gyatso is believed to be the son of the "Great Fifth".[6] He could not be the son of the Fifth Dalai Lama because he was born near Lhasa in September 1653, when the Dalai Lama had been absent on his trip to China for the preceding sixteen months.[7]: 264−322 [8] He ruled as regent, hiding the death of the Dalai Lama, while the infant 6th Dalai Lama was growing up, for 16 years. During this period, he oversaw the completion of the Potala Palace and warded off Chinese politicking.[citation needed]

He is also known for harboring disdain for Tulku Dragpa Gyaltsen, although this lama died in 1656, when Sangye Gyatso was only three years old.[7]: 364−365 According to Lindsay G. McCune in her thesis (2007), Desi Sangye Gyamtso refers in his Vaidurya Serpo to the Lama as the "pot-bellied official" (nang so grod lhug) and states that, following his death, he had an inauspicious rebirth.[9]

Chagpori School of Medicine

Sangye Gyatso founded the School of Medicine and Astrology called Men-Tsee-Khang on Chagpori ('Iron Mountain') in 1694. The college was designed for monastic scholars who would, after learning esoteric arts of medicine and tantrism, mostly remain in the monastery, serving the public as would other monk scholars and lamas. In 1916, Khenrab Norbu, physician to the 13th Dalai Lama, sponsored the construction of the Mentsikhang, a second secular college of Tibetan medicine and astrology. Mentsikhang was designed as a college for 'laypersons' who would, after receiving training, return to their rural areas to work as doctors and educators.[10]

Medical treatise

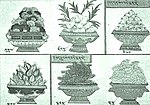

An important part of Sangye Gyatso's contribution to medicine was his composition of the Blue Beryl Treatise and the preparation of a series of nearly 100 medical paintings illustrating medical theory and practice. These paintings were copied and distributed to several other monasteries. A set created in 1920 and preserved in Ulan Ude, Buryatia, was reproduced in facsimile together with a translation of the Blue Beryl Treatise and published in 1992.[2]

Tibetan Buddhist medical concepts

The tradition emphasizes the existence of five major chakras, which are depicted in Blue Beryl as possessing twenty-four spokes, said to symbolize their ability to generate and link with the numerous subtle meridians or currents (Classical Tibetan: rsta). The Brow and Throat centers are associated with the cosmic plane (stod); the Heart center to the human plane (bar); and the Solar and Vitality centers to the earth plane (smad).[11]

Six herbs

Six medicinal substances were in common use in Tibet when they appeared in the Blue Beryl Treatise:[12][2]

- Arabic frankincense (Burseraceae) (see on the left, top-left corner)

- Mongolian garlic (Allium tuberosum) (see on the left, top-middle)

- Chinese quince (Pseudocydonia) (see on the left, top-right corner)

- Indian embelic myrobalan (Terminalia chebula) (see on the left, bottom-left corner)

- Tibetan ginger (Hedychium gardenerianum) (see on the left, bottom-middle)

- South Chinese Kaempferia galanga (see on the left, bottom-right corner)

Regency

Sangye Gyatso became regent or desi of Tibet at the age of 26 in 1679. Three years later, in 1682, the 5th Dalai Lama died. However, his demise was kept secret until 1696-97, and the desi governed Tibet.

From 1679 to 1684, the Ganden Phodrang fought in the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War against the Namgyal dynasty of neighboring Ladakh. Desi Sangye Gyatso[5]: 342 : 351 and the King Delek Namgyal of Ladakh[5]: 351–353 [13]: 171–172 agreed on the Treaty of Tingmosgang in the fortress of Tingmosgang at the conclusion of the war in 1684. The original text of the Treaty of Tingmosgang no longer survives, but its contents are summarized in the Ladakh Chronicles.[14]: 37 : 38 : 40

He entertained close contacts with Galdan Boshugtu Khan, the ruler of the emerging Dzungar Khanate of Inner Asia, with the aim of countering the role of the Khoshut Mongols in Tibetan affairs. The Khoshut khans had functioned as protector-rulers of Tibet since 1642 but their influence had been on the wane since 1655. The supposed reincarnation of the Dalai Lama was born in 1683 and discovered two years later. He was secretly educated in Nankhartse while Sangye Gyatso proceeded to hide the death of his master. It was only in 1697 that the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, was installed.[15] This evoked great irritation from the Qing Kangxi Emperor who had been kept in the dark about the matter, and furthermore was an enemy of the Dzungar rulers. Meanwhile, a new and ambitious Khoshut ruler came to power, Lha-bzang Khan.

The murder of the desi

The Sixth Dalai Lama turned out to be a talented but boisterous young man who preferred poetry-writing and the company of young women to monastic life. In 1702 he renounced his monastic vows and returned to lay status but retained his temporal authority.

In the next year, Sangye Gyatso formally turned over the regent title to his own son, Ngawang Rinchen, but in fact kept the executive powers. Now, a rift emerged within the Tibetan elite. Lha-bzang Khan was a man of character and energy who was not content with the effaced state in which the Khoshut royal power had sunk. He set about to change this, probably after an attempt by Sangye Gyatso to poison the king and his chief minister. Matters came to their head during the Monlam Prayer Festival in Lhasa in 1705, which followed the Losar (New Year). During a grand meeting with the clergy, Sangye Gyatso proposed to seize and execute Lha-bzang Khan. This was opposed by the cleric Jamyang Zhépa from Drepung Monastery, the personal guru of Lha-bzang. Rather, Lha-bzang Khan was strongly recommended to leave for Amdo, the usual abode of the Khoshut elite. He pretended to comply and started his journey to the north.

However, when Lha-bzang Khan reached the banks of the Nagchu River northeast of Ü-Tsang, he halted and began to gather the Khoshut tribesmen. In the summer of 1705 he marched on Lhasa and divided his troops in three columns, one under his wife Tsering Tashi. When Sangye Gyatso heard about this he gathered the troops of Ü-Tsang, Ngari and Kham close to Lhasa. He offered battle but was badly defeated with the loss of 400 men.

The Lobsang Yeshe, 5th Panchen Lama tried to mediate. Realizing that his situation was hopeless, Sangye Gyatso surrendered on condition that he was spared and was sent to Gonggar Dzong west of Lhasa. However, the vengeful Queen Tsering Tashi arrested Sangye Gyatso and brought him to the Tölung Valley, where he was killed, probably on 6 September 1705.[16]

In popular culture

- Sangye Gyatso appears as a minor character in the wuxia novel The Deer and the Cauldron by Jin Yong. He becomes sworn brothers with the protagonist Wei Xiaobao and Galdan Boshugtu Khan.[17]

See also

- Ayurveda

- Tibetan people

- Traditional Chinese medicine

- Traditional Mongolian medicine

- Traditional Tibetan medicine

- Tree of physiology

References

- ^ Medicine Across Cultures: History and Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures (Science Across Cultures: the History of Non-Western Science) by Hugh Shapiro and H. Selin (2006) p.87

- ^ a b c Gyurme Dorje; I︠U︡riĭ Mikhaĭlovich Parfionovich (1992). Gyurme Dorje; I︠U︡riĭ Mikhaĭlovich Parfionovich; Fernand Meyer (eds.). Tibetan medical paintings: Illustrations to the Blue Beryl Treatise of Sangye Gyamtso (1653-1705). The works by Sangye Gyamtso; Dalai Lama XIV, Bstan-’dzin-rgya-mtsho. New York: H.N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-3861-8. OCLC 25508990. ISBN 9780810938618

- ^ Healing Powers and Modernity: Traditional Medicine, Shamanism, and Science in Asian Societies by Linda H. Connor and Geoffrey Samuel (2001) p.267

- ^ Jaroslav Průšek and Zbigniew Słupski, eds., Dictionary of Oriental Literatures: East Asia (Charles Tuttle, 1978): 147.

- ^ a b c Ahmad, Zahiruddin (1968). "New light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal war of 1679—1684". East and West. 18 (3/4): 340–361. JSTOR 29755343.

- ^ Bryan J. Cuevas, Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century: The Capital of the Dalai Lamas, The Journal of Asian Studies (2004), 63: 1124-1127

- ^ a b Dalai Lama V (2014). The Illusive Play: The Autobiography of the Fifth Dalai Lama. Translated by Karmay, Samten G. Chicago: Serindia Publications. ISBN 978-1-932476675.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1998) High Peaks, Pure Earth; Collected Writings on Tibetan History and Culture. Serindia Publications, London. p. 455 ISBN 0906026466

- ^ Tales of Intrigue from Tibet's Holy City: The Historical Underpinnings of a Modern Buddhist Crisis Thesis by Lindsay G. McCune Archived February 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine The Florida State University College of Arts and Sciences, see page 8 of introduction

- ^ Tibet Information Network (2004). Tibetan Medicine in Contemporary Tibet: Health and Health Care in Tibet II. Health and health care in Tibet. Tibet Information Network. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-9541961-7-2. Retrieved 2024-05-16.

- ^ Lade, Arnie (1999). Energetic healing: Embracing the life force (1st ed.). Twin Lakes, Wis. (USA): Lotus. p. 48. ISBN 978-0914955467.

- ^ Gyamtso, S., Klassische Tibetische Medizin (1996) ISBN 978-3-258-05550-3

- ^ Petech, Luciano (1977). The Kingdom of Ladakh: C. 950-1842 A.D. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. ISBN 9788863230581.

- ^ Lamb, Alastair (1965), "Treaties, Maps and the Western Sector of the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute" (PDF), The Australian Year Book of International Law: 37–52

- ^ Tsepon W.D. Shakabpa, Tibet. A political history. Yale 1967, pp. 125-8.

- ^ Luciano Petech, China and Tibet in the early 18th century. Leiden 1950.

- ^ Cha, Louis (2018). Minford, John (ed.). The Deer and the Cauldron: 3 Volume Set. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190836054.