| Resian | |

|---|---|

| Rozajanski langäč / Rozojanski langäč | |

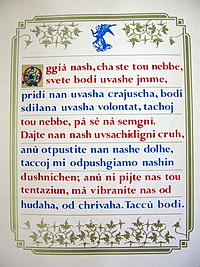

Pater Noster in the old Resian dialect | |

| Native to | Italy |

| Region | Resia valley |

| Ethnicity | Resians[1] |

Native speakers | 929 (2022)[2] |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | University of Padua[3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | resi1246 |

| IETF | sl-rozaj |

The Resian dialect | |

The Resian dialect or simply Resian (self-designation Standard Rozajanski langäč / Rozojanski langäč, Bila Rozajanski langäč / Rozojanski langäč, Osoanë Rozoanske langäč, Solbica Rozajonski langeč / Rozojonski langeč;[3] Slovene: rezijansko narečje [ɾɛziˈjáːnskɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ], rezijanščina; Italian: Dialetto Resiano) is a distinct variety in the South Slavic continuum, generally considered a Slovene dialect spoken in the Resia Valley, Province of Udine, Italy, close to the border with Slovenia.[4][5][6]

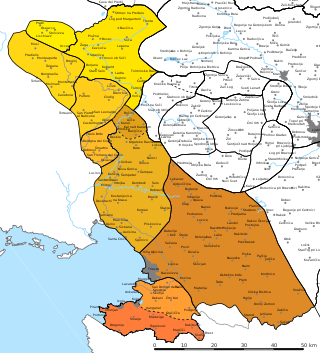

Together with the Rosen Valley dialect and Ebriach dialect in Carinthia, it is one of the three dialects of Slovene spoken entirely outside the borders of Slovenia. It is unequivocally one of the most unique and difficult dialects to understand for speakers of central Slovene dialects, especially because most Resians are not familiar with standard Slovene.[7] Its distinguishing characteristic is centralized, breathy vowels.[8] It borders the Slovene Torre Valley dialect to the south and the Soča dialect to the east, both separated by tall mountain ranges.[9] On the other sides, it mostly borders Friulian, but also Bavarian to the north. It belongs to the Littoral dialect group, although it shows few similarities with other Littoral dialects and evolved from the Carinthian dialect base, northern Slovene, as opposed to other Littoral dialects, which evolved either from western or southern Slovene. It is spoken by fewer than a thousand people and is listed as a definitely endangered language according to UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger.[10] Despite this, Resians value their language and it is being passed down to younger generations.[7]

Geographic extension

The area where Resian is spoken is practically the same as the area of the Municipality of Resia (Italian: Comune di Resia). It is spoken entirely in northeastern Italy, in the Friuli-Venezia Giulia region in the province of Udine, making it the only Slovene dialect that is spoken exclusively in Italy. The speakers are settled in villages in the Resia Valley (Slovene: Rezija), along the Resia River (Rezija), as well as the upper Uccea Valley (Učja) on the Italian side. This includes several villages, including (from west to east): San Giorno (Bilä, Bela), Prato di Resia (Ravanca), Gniva (Njïwa, Njiva), Criacis (Krïžaca, Križeca), Oseacco (Osoanë, Osojane), Carnizza (Karnïca, Karnica), Stolvizza (Solbica), Coritis (Korïto, Korito), and Uccea (Učja).[11] The Resia Valley is open to the west, where Friulian is spoken, and separated by tall mountains in other directions. There is a road connecting it to the Uccea Valley, reaching an elevation of more than 1,100 m above sea level, and it is further connected to the Torre and Soča Valleys, where Slovene is spoken. To the south, it is bordered by the Musi (Mužci) Mountains, to the east by Mount Canin (Ćanen, Kanin), and to the north by Mount Sard (Žard), therefore limiting possible connections with neighboring dialects and languages, which in turn has led to so many distinct features of Resian dialect.[9]

The area was settled by Slovenes from the north, the area of today's Gail Valley dialect. Both areas remained connected until the 14th century, when sparsely populated Slovenes living in the Raccolana and Dogna Valleys started speaking Romance languages. There is no Slovene-speaking minority in that area today because it is mainly populated by Friulian and German speakers.[12]

Standard Resian

Standard Resian was developed by Han Steenwijk from the University of Padua and his colleagues Alfonso Barazzutti, Milko Matičetov, Pavle Merkù, Giovanni Rotta, and Willem Vermeer in the 1990s and continuing today. To date, they have standardized the writing, pronunciation,[13] and declension.[14] At first it was suggested to base the standard language on a central microdialect, particularly that of Gniva (Njïva, Njiva), but later it was decided to allow four forms of standard Resian, based on the four microdialects of four larger villages: San Giorno (Bila, Bela), Gniva (Njïva, Njiva), Oseacco (Osoanë, Osojane), and Stolvizza (Solbica).[15] For other areas of grammar, only the microdialect of San Giorno can be used because it is the only one described in sufficient detail thanks to Steenwijk's extensive research.[16]

Characteristics

Resian belongs to the western subgroup of the South Slavic branch of the Slavic languages, together with Slovene, which includes the Natisone Valley dialect, and Serbo-Croatian. It represents the far northwestern part of the dialect continuum. The closest written language is the Natisone Valley dialect and the closest standard language is Slovene. The closest (other) Slovene dialect is the Torre Valley dialect, another dialect known for little mutual intelligibility with other dialects.[17] Written Resian can be understood by most Slovenes, partially also due to its similar orthography. Spoken Resian, however, is much more difficult to understand, with the main reason being centralization of vowels, making them more difficult to distinguish. Speakers of the Torre Valley and Natisone Valley dialects, as well as other dialects in Littoral dialect group, can understand spoken Resian most easily because they have the most shared features and they all have extensive vocabulary from Friulian and Italian.[17]

Mutual intelligibility with other South Slavic languages is even more difficult, although Resian has undergone the *sěnȏ > *sě̀no accent shift,[18] and so these words are now accented on the same syllable as in Serbo-Croatian, as opposed to most Slovene dialects.

Language vs. dialect

There is disagreement between native speakers of the dialect and linguists regarding whether Resian should be considered a separate language or only a dialect of Slovene. Resians were isolated from other Slovenes from the 14th century onward, before standard Slovene was developed, and later they never had the chance to learn it because there were no Slovene schools in that area and none of the Italian schools taught Slovene, not even as a foreign language. Resians thus not only have a hard time understanding Slovene, but they also do not feel themselves part of the Slovene nation because they were left out, and they consider themselves an ethnic group separate from Slovenes. In 2004, 1,014 out of 1,285 (78.9%) inhabitants of Resia signed a petition declaring that they are not Slovenes.[1] The dialect also has its own orthography, which existed and was actively used even before standardization. Resian is also used instead of standard Slovene on bilingual signs and in public announcements.[19]

On the other hand, linguists have always treated Resian as a dialect. It does not show any features sufficiently distinct to qualify it as a separate language.[20][21][22] To avoid disputes, it is thus often referred to as a Slavic microlanguage.[23]

Accent

The Resian dialect, in contrast to neighboring dialects, does not have pitch accent and seems to have lost distinctions in vowel length, with the only difference in length being tied to stress (stressed vowels are longer than short)[24] and breathiness (breathy vowels are shorter than non-breathy),[24][25] although standard Resian forms still differentiate between length. From the historical perspective, Resian has undergone only the *sěnȏ > *sě̀no accent shift since Alpine Slovene,[18] making it two accent shifts different from standard Slovene, which has not undergone the *sěnȏ > *sě̀no accent shift, but has undergone the *ženȁ → *žèna and optionally *məglȁ → *mə̀gla accent shifts.[26]

Phonology

Due to years of isolated evolution from other Slovene dialects, Resian has developed some iconic features, particularly breathy, centralized vowels that are almost exclusive to Resian, with only some microdialects of the Torre Valley dialect also having a similar sound.[27] Its consonant inventory is shared with the Littoral dialects, retaining palatal sounds.

Consonants

Han Steenwijk recorded 25 consonant phonemes in San Giorno (Bila, Bela) and then also generalized the pronunciation to the other three standard forms, which are definitely similar, except that Stolvizza (Solbica) has somewhat different allophones for /g/ and /x/.[28] Tine Logar also recorded the phoneme /dz/.[29]

| Labial | Dental/ | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | c | k | |

| voiced | b | d | ɟ | ɡ | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | |||

| voiced | (dz) | dʒ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | |

| voiced | z | ʒ | ||||

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | w | ||

| Trill | r | |||||

Vowels

In contrast to consonants, vowels differ significantly between the four microdialects, especially in accented syllables. They all have thoroughly researched accented vowels; however, Oseacco (Osoanë, Osojane) lacks research on unaccented vowels. This is the accent system for San Giorno (Bila, Bela):[31]

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | i | ɨ | ʉ | u |

| Close-mid | e | ə̝ | ɵ | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ə | ɔ | |

| Near-open | ɐ | |||

| Open | a | |||

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | |||

| Close | i | u | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ə | ɵ | ɔ |

| Open | a | |||

Evolution

The evolution of Resian into such a distinct dialect happened gradually and in three stages. The first stage lasted until the 14th century; at that time, Resian was mostly influenced by the Gail Valley dialect. In the second stage, it acquired many features of Venetian Slovene dialects and other Littoral dialects. The third stage represents changes that are unique to Resian and cannot be found elsewhere.

First stage

Until the 13th century, Resian experienced the same evolution as all other Slovene dialects, forming into Alpine Slovene.[32] It was part of the northwestern dialect because long yat diphthongized into *ie and long *ō diphthongized into *uo. It did not experience denasalization of nasal vowels.[33] After further division, it fell into the category of the northern dialect, the same as other Carinthian dialects and unlike other Littoral dialects. It thus did not experience lengthening of non-final vowels at that time, because vowel lengthening in northern dialects happened only after the 16th century, well past the point when Resian lost contact with the Carinthian dialects and leading to possible different reflexes for formerly long and short vowels.[34][35] Long *ə̄ also turned into *ē, which is unique to Resian in comparison to other Littoral dialects because there it turned into *a.[36] The evolution then continued the same as with other Carinthian dialects, leading to the Carinthian dialect base. Short non-final *ě̀, *ò, and è evolved differently from their long counterparts, into *é, ó, and é, respectively. Long *ē turned into *ẹ̄, whereas the nasal vowels remained intact and only lengthened. Long *ə̄ turned into a very open ȩ̄ and short non-final vowels lengthened.[37]

Later, Resian followed the same patterns as the Jaun Valley dialect, such as *ie and *uo simplifying into *iə and *uə, *é and ó turned into *ẹ and *ọ, and the *sěnȏ > *sě̀no accent shift, as well as the merger of *ē and *ě̄. Long nasal vowels also denasalized and *ę̄ merged with *ə̄, resulting in *ē and *ō.[38]

Second stage

The second stage was primarily influenced by the Torre Valley dialect. Open *ē and *ō became close-mid *ẹ̄2 and *ọ̄2 (in contrast to previously existing *ẹ̄1 and *ọ̄1). Short *ə turned into *a, *ĺ turned into *i̯, *w started turning into *v before front vowels, and *ł turned into *l. This connection also hindered some developments, such as *t → č, the *ženȁ > *žèna shift, and the *məglȁ > *mə̀gla shift, which are present today in the Gail Valley dialect, but not in Resian. Final -m in most cases also turned into -n, a feature that also appeared in the Gail Valley dialect. The dialect also devoiced all final obstruents.[39]

Third stage

Resian lost both tonal and length oppositions, which is unlike any neighboring dialect. The diphthongs *iə and *uə monophthongized into *í2 and *ú2, respectively, forming a vowel system without diphthongs, another feature of Resian not seen in any neighboring dialects. The vowels *ọ́1 and *ẹ́1 turned into o̤ and e̤, which might have actually happened before *ọ́2 and *ẹ́2. Now only *ọ́ and *ẹ́ turned into *i and *u near a nasal consonant. Other changes did not cover the entire territory. The vowels *í1 and *ú1 from previously longer syllables turned into i̤ and ṳ, except in San Giorno (Bila, Bela), where previously short *í1 and *ú1 turned into centralized vowels, whereas elsewhere they turned into e and o. Syllabic *ł̥́ mostly turned into ol, except in Oseacco (Osoanë, Osojane) and Uccea (Učja), where it turned into ú. The consonant *ɣ then turned into h, or even disappeared. Other changes are specific to each microdialect.[39]

Morphology

Resian retained neuter gender, as well as some dual forms. It uses the long infinitive without the final -i.

Its special feature is the distinction between animate and inanimate masculine o-stem nouns in more than just the accusative case; the distinction is also present in the dative and locative singular. In the locative, the ending -u can be used for both animate and inanimate, whereas the ending -e̤ is generally reserved for inanimate nouns. In the dative, animate nouns have the ending -ovi/-evi. Specific to Resian are also special unstressed forms for pronouns in the nominative case—for example, ja 'I'—as well as clitic doubling; for example, Ja si ti rë́kal tabë́. 'I told you'. It also has two stressed first-person singular pronouns, jä́ and jä́s, the second being used to be more conceited. Atypical for a Slavic language, Resian also has a definite article (masculine te, feminine ta; the only standard Slavic languages to contain definite articles are Bulgarian and Macedonian) and an indefinite article. It retained the aorist and imperfect until recently, which is unlike (other) Slovene dialects. The aorist is completely unknown to living generations but it was still present in the 19th century, whereas the imperfect is actively used only with a handful of verbs and is now mostly used as a past conditional.[40]

Orthography

The standard orthography, devised in 1994 by Han Steenwijk, which is still in use today, has 34 letters for Gniva (Njïwa, Njiva) and Oseacco (Osoanë, Osojane), whereas the other two standard forms have an additional letter, ⟨y⟩.

The alphabet contains the letter ⟨w⟩, a letter that few Slavic languages use (only Polish, Kashubian, and Upper and Lower Sorbian). According to the Italian linguist Bartoli, this grapheme is characteristic of the Ladin language of the eastern Alps and indicates the native Neolatin population's strong influence on Resian.

The standard orthography uses only the letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet plus eleven other letters, which are letters from the ISO basic Latin alphabet with added acute, caron, or diaeresis:[13]

| Letter | Phoneme:

San Giorno (Bila, Bela) standard version |

Example word | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | /a/ | parjät 'to seem' | [parˈjɐt] parjät |

| Ä ä | /ɐ/ | tatä 'aunt' | [taˈtɐ] tatä |

| B b | /b/ | baba 'grandma' | [ˈbaba] bába |

| C c | /ts/ | cöta 'cloth' | [ˈt͡sɵta] cö́a |

| Č č | /tʃ/ | čäs 'time' | [ˈt͡ʃɐs] čäs |

| Ć ć | /c/ | ćamïn 'chimney' | [caˈmɨn] ćamïn |

| D d | /d/ | sidët 'to sit' | [siˈdət] sidët |

| E e | /ɛ/ | maještra 'teacher' | [maˈjɛʃtra] majéštra |

| Ë ë | /ə/ | kë 'where' | [ˈkə] kë |

| F f | /f/ | fïn 'thin' | [ˈfɨn] fïn |

| G g | /g/ | goba 'mushroom' | [ˈgɔba] góba |

| Ǧ ǧ | /dʒ/ | ǧelato 'ice cream' | [ˈdʒɛlatɔ] ǧeláto |

| Ǵ ǵ | /ɟ/ | ǵanaral 'general' | [ɟanaˈral] ǵanarál |

| H h | /x/ | mihak 'soft' | [ˈmixak] míhak |

| I i | /i/ | paǵina 'page' | [ˈpaɟina] páǵina |

| Ï ï | /ɨ/ | pïsat 'to write' | [ˈpɨsat] pïsat |

| J j | /j/ | jüšt 'right' | [ˈjʉʃt] jüšt |

| K k | /k/ | kjüč 'key' | [ˈkjʉt͡ʃ] kjüč |

| L l | /l/ | listyt 'to fly' | [lisˈtə̝t] listýt |

| M m | /m/ | mama 'mom' | [ˈmama] máma |

| N n | /n/ | natik 'fast' | [naˈtik] natík |

| O o | /ɔ/ | parsona 'person' | [parˈsɔna] parsóna |

| Ö ö | /ɵ/ | patök 'stream' | [paˈtɵk] patök |

| P p | /p/ | grüpo 'group' | [ˈgɾʉpɔ] grüpo |

| R r | /r/ | dyržat 'to hold' | [ˈdə̝rʒat] dýržat |

| S s | /s/ | sam 'alone' | [ˈsam] sám |

| Š š | /ʃ/ | šëjst 'six' | [ˈʃəjst] šëjst |

| T t | /t/ | tatä 'aunt' | [taˈtɐ] tatä́ |

| U u | /u/ | klubük 'hat' | [kluˈbʉk] klubük |

| Ü ü | /ʉ/ | cükër 'sugar' | [ˈt͡sʉkər] cükër |

| V v | /ʋ/ | vys 'village' | [ˈʋə̝s] výs |

| W w | /w/ | wïža 'song' | [ˈwɨʒa] wïža |

| Y y | /ə̝/ | byt 'to be' | [ˈbə̝t] být |

| Z z | /z/ | zalën 'green' | [zaˈlən] zalë́n |

| Ž ž | /ʒ/ | žanä 'woman' | [ʒaˈnɐ] žanä |

Previously, the phoneme /ts/ could optionally also be written with ⟨z⟩ (e.g., Ravanza instead of Ravanca); however that is found inappropriate today. Despite the standard orthography, many street signs are still not adapted to the new orthography and have misspelled names on them.[19]

In addition, the acute accent ( ´ ) can be used to mark stress where it cannot be inferred.

Literature

The first written texts in Resian were already written in the 18th century. The first known instances are two manuscripts called Rez'janskij katichizis I and II, which are thought to have been written after 1700, but the exact date remains unclear because only copies exist, one of them being dated to 1797. The first manuscript must have been written before the second because it contains archaisms not seen in the second manuscript. The second known manuscript is Passio Domini ec., which has been dated between 1830 and 1848 but was probably written by a nonnative speaker. The first longer piece, spanning over 95 pages, was Christjanske uzhilo, dated to somewhere between 1845 and 1850, but it was still a manuscript. The first book was To kristjanske učilo po rozoanskeh, written by Giuseppe Cramaro sometime between 1923 and 1933. There are also numerous instances of Resian written by scholars that studied the dialect.[41]

Literature written in Resian is still being published; for instance, in 2021 Silvana Paletti and Malinka Pila published a Resian translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince.[42]

Research

Notable linguists who have studied the dialect include Jan Niecisław Baudouin de Courtenay, Eric Hamp, Milko Matičetov, and Roberto Dapit.

Encoding

The IETF language tags have registered:[43]

sl-rozajfor the dialect in general.sl-rozaj-1994for text in the 1994 standard orthography.

sl-rozaj-biskefor the subdialect of San Giorgio/Bila.sl-rozaj-biske-1994for text in the 1994 standard orthography.

sl-rozaj-lipawfor the subdialect of Lipovaz/Lipovec.sl-rozaj-lipaw-1994for text in the 1994 standard orthography.

sl-rozaj-njivafor the subdialect of Gniva/Njiva.sl-rozaj-njiva-1994for text in the 1994 standard orthography.

sl-rozaj-osojsfor the subdialect of Oseacco/Osojane.sl-rozaj-osojs-1994for text in the 1994 standard orthography.

sl-rozaj-solbafor the subdialect of Stolvizza/Solbica.sl-rozaj-solba-1994for text in the 1994 standard orthography.

See also

References

- ^ a b ""Siamo resiani e non sloveni" Mille firme per un referendum" ["We are Resians and not Slovenians" One thousand signatures for a referendum]. Il Messaggero. February 5, 2004.

- ^ "Popolazione residente al 1° Gennaio 2022 per sesso, età e stato civile - dati provvisori; Comune: Resia" [Resident population on 1st January 2022 by gender, age and marital status – data provider; Comune: Resia]. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (in Italian and English). 1 January 2022. Archived from the original on 11 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ a b Steenwijk, Han (15 April 2004). "Resian dictionary". Resianica (in English, Italian, and Slovenian). University of Padua. Archived from the original on 19 January 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Steenwijk (1992a:1)

- ^ Pronk, Tijmen (2009). The Slovene Dialect of Egg and Potschach in the Gailtal, Austria. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 2.

- ^ Stankiewicz, Edward (1986). The Slavic Languages: Unity in Diversity. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 93.

- ^ a b Logar (1996:231)

- ^ Logar (1996:4)

- ^ a b "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, UNESCO's Endangered Languages Programme, retrieved 2015-10-17

- ^ Vidau (2021:60)

- ^ Logar (1996:233)

- ^ a b Steenwijk (1994)

- ^ Steenwijk (1999)

- ^ Steenwijk, Han (1992b). "Verso la grammatica pratica del resiano" [Towards the practical grammar of the Resian]. Resianica (in Italian). Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Steenwijk (1992a)

- ^ a b Logar, Tine (1970). "Slovenski dialekti v zamejstvu". Prace Filologiczne. 20: 84. ISSN 0138-0567.

- ^ a b Šekli (2018:310–314)

- ^ a b Vidau (2021:60–61)

- ^ Ahačič, Kozma; Škofic, Jožica; Gliha Komac, Nataša; Gostenčnik, Januška; Ježovnik, Janoš; Kenda-Jež, Karmen; Šekli, Matej; Škofic, Jožica; Zuljan Kumarr, Danila (2020). "Zakaj je nadiško narečje v Italiji slovensko narečje" [Why is Natisone dialect in Italy a Slovene dialect] (pdf). Jezikovni zapiski [Language notes]. 26/2020/1 (in Slovenian). ZRC SAZU. pp. 219–223. doi:10.3986/Jz.26.1.15. S2CID 216486109. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ Rigler, Jakob (1986). Razprave o slovenskem jeziku. Ljubljana: Slovenska Matica v Ljubljani. p. 100.

- ^ Natale Zuanella (1978). "Informacija o jezikovnem položaju v Beneški Sloveniji – Informazione sulla realtà linguistica della Slavia Veneta". Atti: conferenza sui Gruppi Etnico Linguistici della Provincia di Udine. Cividale del Friuli: SLORI. p. 273.

- ^ Šekli, Matej (2015). "Slovanski knjižni mikrojeziki: opredelitev in prikaz pojava znotraj slovenščine" [Slavic literary microlanguages: characterization and display of the feature inside Slovene language.] (PDF). Država in narod v slovenskem jeziku, literaturi in kulturi (in Slovenian) (1st ed.). Ljubljana: Znanstvena založba Filozofske fakultete. p. 95. ISBN 978-961-237-753-3.

- ^ a b Logar (1996:248)

- ^ Rigler, Jakob (2001). "V Ocene in polemike: O rezijanskem naglasu" [V Evaluations and polemics: About Resian accent]. In Smole, Vera (ed.). Zbrani spisi / Jakob Rigler [Collected essays / Jakob Rigler] (in Slovenian). Vol. 1: Jezikovnozgodovinske in dialektološke razprave. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC. pp. 494–495. ISBN 961-6358-32-4.

- ^ Šekli (2018:311–312)

- ^ Ježovnik, Janoš (2019). Notranja glasovna in naglasna členjenost terskega narečja slovenščine (pdf) (in Slovenian). Ljubljana. p. 26. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Steenwijk (1992a:14)

- ^ Logar (1996:122)

- ^ Steenwijk (1992a:20)

- ^ Steenwijk (1992a:19–20)

- ^ Šekli (2018:297)

- ^ Šekli (2018:297–300)

- ^ Rigler (2001:315)

- ^ Šekli (2018:300–302)

- ^ Šekli (2018:303)

- ^ Šekli (2018:325)

- ^ Logar (1996:233)

- ^ a b Logar (1996:233–236)

- ^ Benacchio, Rosana (1998). "Oblikoslovno-skladenjske posebnosti rezijanščine" [Morphologically-sytactical features of Resian]. Slavistična revija: časopis za jezikoslovje in literarne vede [Journal for linguistics and literary studies]. 46/3 (in Slovenian). Translated by Gruden, Živa. Ljubljana: Slavistično društvo Slovenije. pp. 249–259. ISSN 0350-6894.

- ^ Steenwijk, Han (2003). The Roots of Written Resian. Padua. pp. 313–322. S2CID 209507567.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Te Mali Prïncip (verlag-tintenfass.de)

- ^ "IETF Language Subtag Registry". IANA. 2021-08-06. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

Bibliography

- Logar, Tine (1996). Kenda-Jež, Karmen (ed.). Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave [Dialectological and etymological discussions] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- Steenwijk, Han (1992a). Barentsen, A. A.; Groen, B. M.; Sprenger, R. (eds.). The Slovene dialect of Resia: San Giorno. Vol. 18. Amsterdam - Atlanta: Rodopi. ISBN 90-5183-366-0.

- Steenwijk, Han (1994). Ortografia resiana = Tö jošt rozajanskë pïsanjë (in Italian and Slovenian). Padua: CLEUP.

- Steenwijk, Han (1999). Grammatica pratica resiana: il sostantivo (in Italian and Slovenian). Padua: CLEUP. ISBN 88-7178-646-7.

- Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Tipologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Vidau, Zaira (12–19 November 2021). "Ocena stanja izvajanja določil iz 10. člena Zaščitnega zakona št. 38/2001 o krajevnih imenih in javnih napisih" [Evaluation of the state of execution of provision from 10th article of Preservation law number 38/2001 about settlement names and public inscriptions]. In Jagodic, Devan (ed.). Tretja deželna konferenca o varstvu slovenske jezikovne manjšine [Third provincial conference about preservation of Slovene language minority] (PDF) (in Slovenian). Translated by Castegnaro, Laura; Clerici, Martina; Umer Kljun, Jerneja. Trieste/Trst: Slovene research institute. pp. 60–61. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

External links

- Resianic homepage Archived 2006-05-06 at the Wayback Machine, containing texts in Italian, German, Slovenian, and English, as well as a Resian-Slovenian dictionary