| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Navelbine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695013 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | intravenous, by mouth[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 43 ± 14% (oral)[3] |

| Protein binding | 79 to 91% |

| Metabolism | liver (CYP3A4-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 27.7 to 43.6 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal (46%) and kidney (18%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

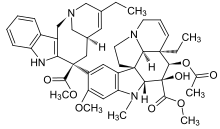

| Formula | C45H54N4O8 |

| Molar mass | 778.947 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Vinorelbine (NVB), sold under the brand name Navelbine among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat a number of types of cancer.[4] This includes breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer.[4] It is given by injection into a vein or by mouth.[4][1]

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression, pain at the site of injection, vomiting, feeling tired, numbness, and diarrhea.[4] Other serious side effects include shortness of breath.[4] Use during pregnancy may harm the baby.[4] Vinorelbine is in the vinca alkaloid family of medications.[1] It is believed to work by disrupting the normal function of microtubules and thereby stopping cell division.[4]

Vinorelbine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1994.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5]

Medical uses

Vinorelbine is approved for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer.[6][7] It is used off-label for other cancers such as metastatic breast cancer and for aggressive fibromatosis (desmoid tumor).[8][9] It is also active in rhabdomyosarcoma.[10]

Side effects

Vinorelbine has a number of side-effects that can limit its use:

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (a progressive, enduring and often irreversible tingling numbness, intense pain, and hypersensitivity to cold, beginning in the hands and feet and sometimes involving the arms and legs[11]), lowered resistance to infection, bruising or bleeding, anaemia, constipation, vomitings, diarrhea, nausea, tiredness and a general feeling of weakness (asthenia), inflammation of the vein into which it was injected (phlebitis). Seldom severe hyponatremia is seen.

Less common effects are hair loss and allergic reaction.

Pharmacology

The antitumor activity is due to inhibition of mitosis through interaction with tubulin.[12]

History

Vinorelbine was invented by the pharmacist Pierre Potier and his team from the CNRS in France in the 1980s and was licensed to the oncology department of the Pierre Fabre Group. The drug was approved in France in 1989 under the brand name Navelbine for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. It gained approval to treat metastatic breast cancer in 1991. Vinorelbine received approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 1994 sponsored by Burroughs Wellcome Company. Pierre Fabre Group now markets Navelbine in the U.S., where the drug went generic in February 2003.

In most European countries, vinorelbine is approved to treat non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer. In the United States it is approved only for non-small cell lung cancer.

Sources

The Madagascan periwinkle Catharanthus roseus L. is the source for a number of important natural products, including catharanthine and vindoline[13] and the vinca alkaloids it produces from them: leurosine and the chemotherapy agents vinblastine and vincristine, all of which can be obtained from the plant.[14][15][6][16] The newer semi-synthetic chemotherapeutic agent vinorelbine, which is used in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer[6][7] and is not known to occur naturally. However, it can be prepared either from vindoline and catharanthine[6][17] or from leurosine,[18] in both cases by synthesis of anhydrovinblastine. The leurosine pathway uses the Nugent–RajanBabu reagent in a highly chemoselective de-oxygenation of leurosine.[19][18] Anhydrovinblastine is then reacted sequentially with N-bromosuccinimide and trifluoroacetic acid followed by silver tetrafluoroborate to yield vinorelbine.[17]

Oral formulation

An oral formulation has been marketed and registered in most European countries. It has similar efficacy as the intravenous formulation, but it avoids venous toxicities of an infusion and is easier to take.[medical citation needed] The oral form is not approved in the United States, or Australia.[medical citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 594. ISBN 9780857111562.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ Marty M, Fumoleau P, Adenis A, Rousseau Y, Merrouche Y, Robinet G, et al. (November 2001). "Oral vinorelbine pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability study in patients with solid tumors". Annals of Oncology. 12 (11): 1643–1649. doi:10.1023/A:1013180903805. PMID 11822766.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Vinorelbine Tartrate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ a b c d Keglevich P, Hazai L, Kalaus G, Szántay C (May 2012). "Modifications on the basic skeletons of vinblastine and vincristine". Molecules. 17 (5): 5893–5914. doi:10.3390/molecules17055893. PMC 6268133. PMID 22609781.

- ^ a b Faller BA, Pandit TN (2011). "Safety and efficacy of vinorelbine in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer". Clinical Medicine Insights: Oncology. 5: 131–144. doi:10.4137/CMO.S5074. PMC 3117629. PMID 21695100.

- ^ Saiyed MM, Ong PS, Chew L (June 2017). "Off-label drug use in oncology: a systematic review of literature". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 42 (3): 251–258. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12507. PMID 28164359.

- ^ Alman B, Attia S, Baumgarten C, Benson C, Blay J, Bonvalot S, et al. (March 2020). "The management of desmoid tumours: A joint global consensus-based guideline approach for adult and paediatric patients". European Journal of Cancer. 127: 96–107. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.013. hdl:2434/809127. PMID 32004793.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Casanova M, Ferrari A, Spreafico F, Terenziani M, Massimino M, Luksch R, et al. (June 2002). "Vinorelbine in previously treated advanced childhood sarcomas: evidence of activity in rhabdomyosarcoma". Cancer. 94 (12): 3263–3268. doi:10.1002/cncr.10600. PMID 12115359. S2CID 21824468.

- ^ del Pino BM (Feb 23, 2010). "Chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy". NCI Cancer Bulletin. 7 (4): 6. Archived from the original on 2011-12-11.

- ^ Jordan MA, Wilson L (April 2004). "Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 4 (4): 253–265. doi:10.1038/nrc1317. PMID 15057285. S2CID 10228718.

- ^ Hirata K, Miyamoto K, Miura Y (1994). "Catharanthus roseus L. (Periwinkle): Production of Vindoline and Catharanthine in Multiple Shoot Cultures". In Bajaj YP (ed.). Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry 26. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Vol. VI. Springer-Verlag. pp. 46–55. ISBN 9783540563914.

- ^ Gansäuer A, Justicia J, Fan C, Worgull D, Piestert F (2007). "Reductive C—C bond formation after epoxide opening via electron transfer". In Krische MJ (ed.). Metal Catalyzed Reductive C—C Bond Formation: A Departure from Preformed Organometallic Reagents. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 279. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 25–52. doi:10.1007/128_2007_130. ISBN 9783540728795. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- ^ Cooper R, John J (2016). "Africa's gift to the world". Botanical Miracles: Chemistry of Plants That Changed the World. CRC Press. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9781498704304. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- ^ Raviña E (2011). "Vinca alkaloids". The evolution of drug discovery: From traditional medicines to modern drugs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9783527326693. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- ^ a b Ngo QA, Roussi F, Cormier A, Thoret S, Knossow M, Guénard D, et al. (January 2009). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of vinca alkaloids and phomopsin hybrids". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 52 (1): 134–142. doi:10.1021/jm801064y. PMID 19072542.

- ^ a b Hardouin C, Doris E, Rousseau B, Mioskowski C (April 2002). "Concise synthesis of anhydrovinblastine from leurosine". Organic Letters. 4 (7): 1151–1153. doi:10.1021/ol025560c. PMID 11922805.

- ^ Morcillo SP, Miguel D, Campaña AG, de Cienfuegos LÁ, Justicia J, Cuerva JM (2014). "Recent applications of Cp2TiCl in natural product synthesis". Organic Chemistry Frontiers. 1 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1039/c3qo00024a. hdl:10481/47295.

External links

- "Vinorelbine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.